Backstage with Matthew: Magic Flute Design

The production we are bringing to San Francisco must rank as one of the most successful interpretations, having been staged in more than 40 opera houses around the world. Australian director Barrie Kosky teamed up with the British theatre company 1927 and Suzanne Andrade to create this fascinating and utterly charming take on The Magic Flute. I spent a little time recently with the production designer Esther Bialas and our head of wig and make up, Jeanna Parham, to learn more.

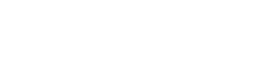

Photo by Cory Weaver

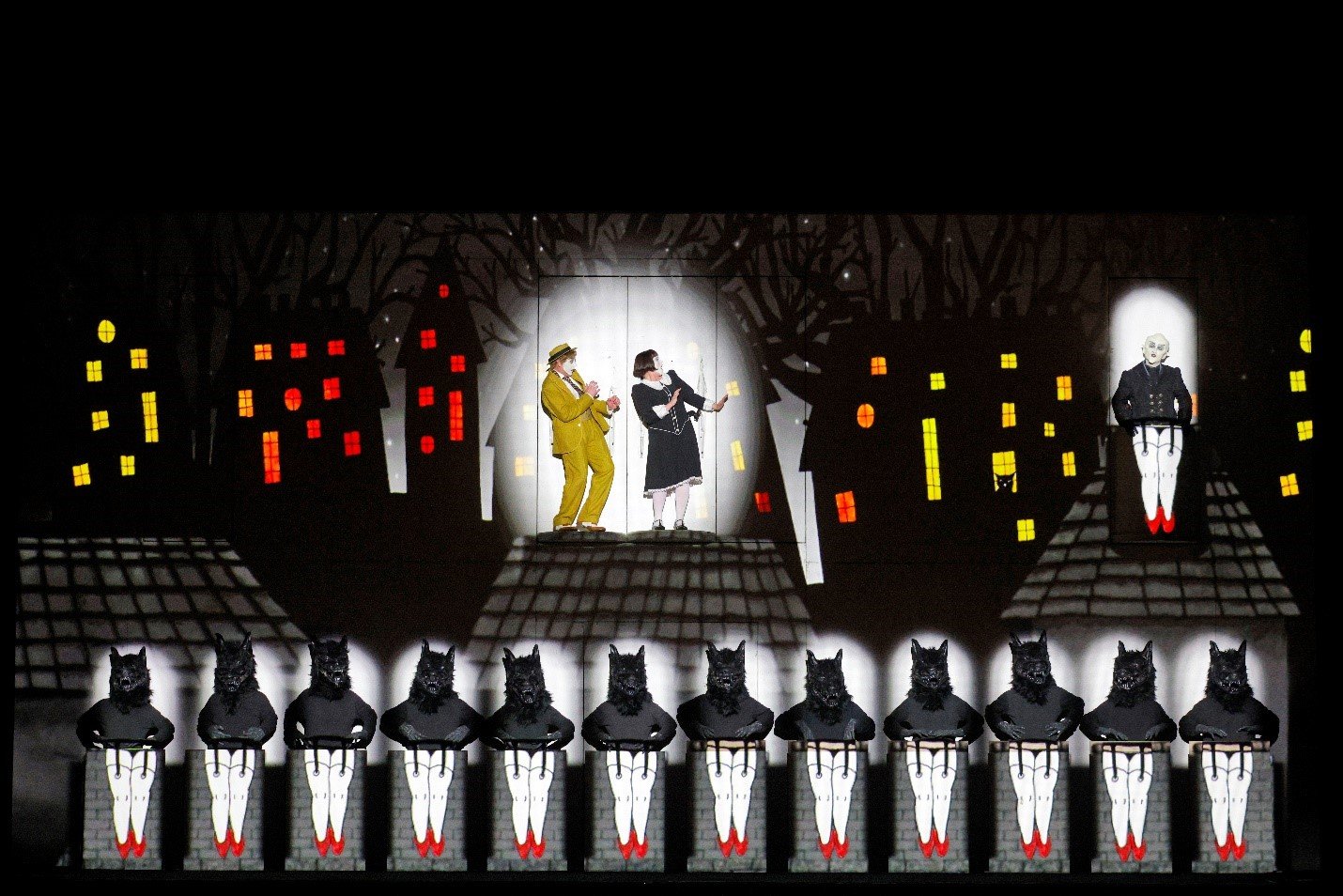

The production originated at the Komische Oper in Berlin in 2012, with a parallel version made by co-producer LA Opera. The impetus and name for the theatre company 1927 is the year during which silent film gave way to ‘talkies,’ and that juncture point is so fabulously expressed here. The whole set is projected onto a wall, in which singers pop in and out through ingenious revolving doors. The singers are generally fixed in place while wonderfully whimsical projections by Paul Barritt move around them. The dialogue is replaced by text redolent of silent film captions, creating an incredibly tight performance. The production is a unique hybrid of film and live performance, interacting symbiotically with some 800 projection cues.

Pamina (Christina Gansch) with Monostatos (Zhengyi Bai) and an example of the interaction of projected and live action (photo by Cory Weaver).

Pamina (Christina Gansch) with Monostatos (Zhengyi Bai) and an example of the interaction of projected and live action (photo by Cory Weaver).

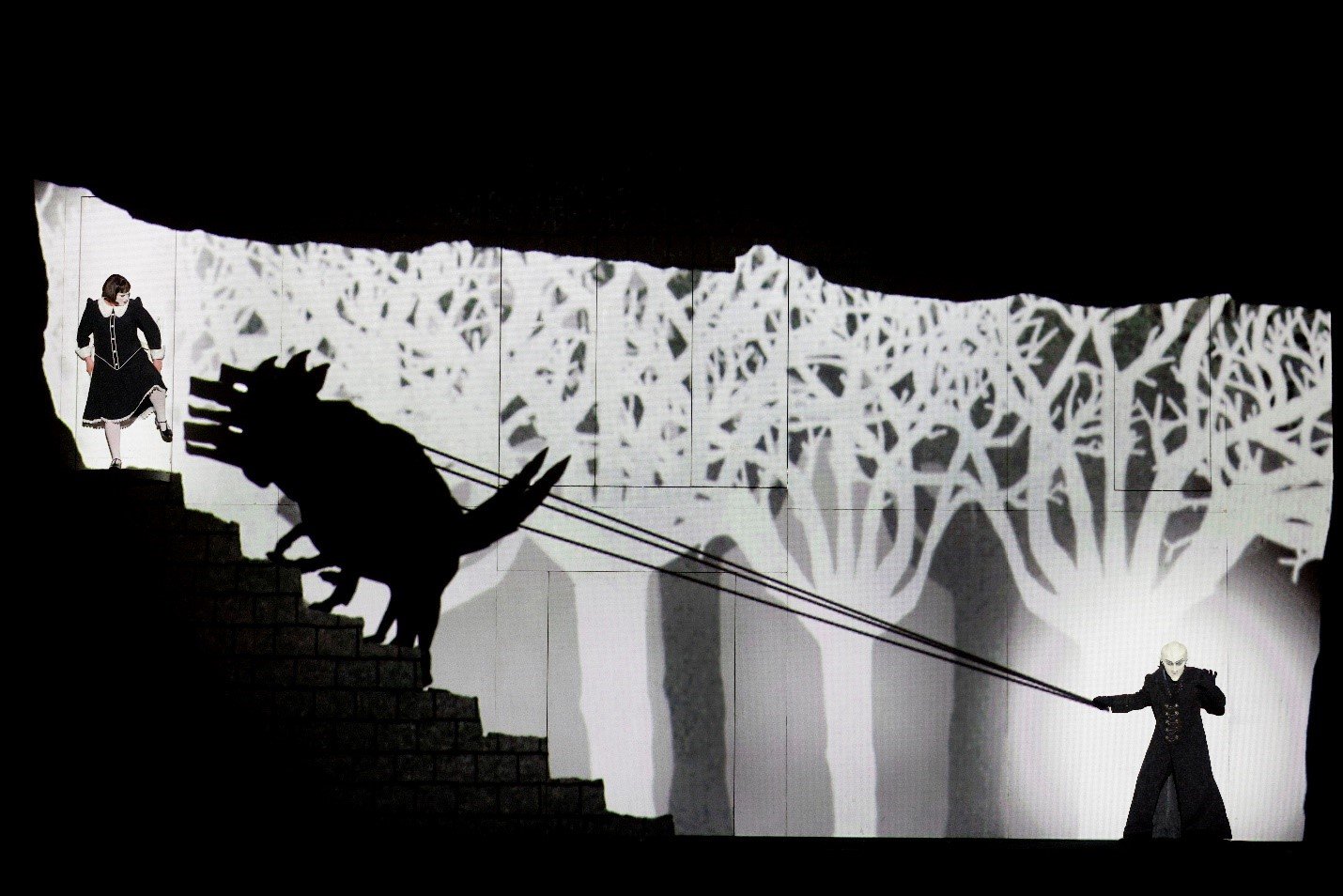

Production designer Esther Bialas shared with me that the original concept was to have 13 revolving doors in the wall, but ultimately that was reduced to six. Each door needs two crew members to operate it, along with stage management support and, as you’ll see when you watch the opera, it is a constant interplay of people revolving in and out. Originally the hope in Berlin was to have computerized door mechanisms, but Esther is grateful that it ended up being a manual system. It allows the crew members to be completely responsive to the singers’ needs, giving singers reassurance knowing there are people on the other side of the doors. The design of the doors then also became about logistics: how many people at any one point; how much head room to accommodate the heights of different singers (and their top hats); and how the projections interact with the drama. Some of the logistical solutions are fabulously creative: the harness system works with a car seatbelt system allowing for quick release; and Esther needed a slimline chair for singers to sit on at times while perched on the ledge. After exploring many options, the perfect solution was found in a bike seat!

Collette Berg (assistant stage manager), cueing the door action, and members of the carpentry crew operating the doors

Collette Berg (assistant stage manager), cueing the door action, and members of the carpentry crew operating the doors

Just some of the harnesses: each singer and cover have their own harness with which they lock into the door

Esther mentioned how helpful it was to design both sets and costumes because so many of the challenges needed to be solved simultaneously. The doors and platforms don’t give the singers much space, if any, to move around, and so clothes need to be supportive of that limitation.

This side view gives you a sense of how narrow the platforms are on which the singers stand.

This side view gives you a sense of how narrow the platforms are on which the singers stand.

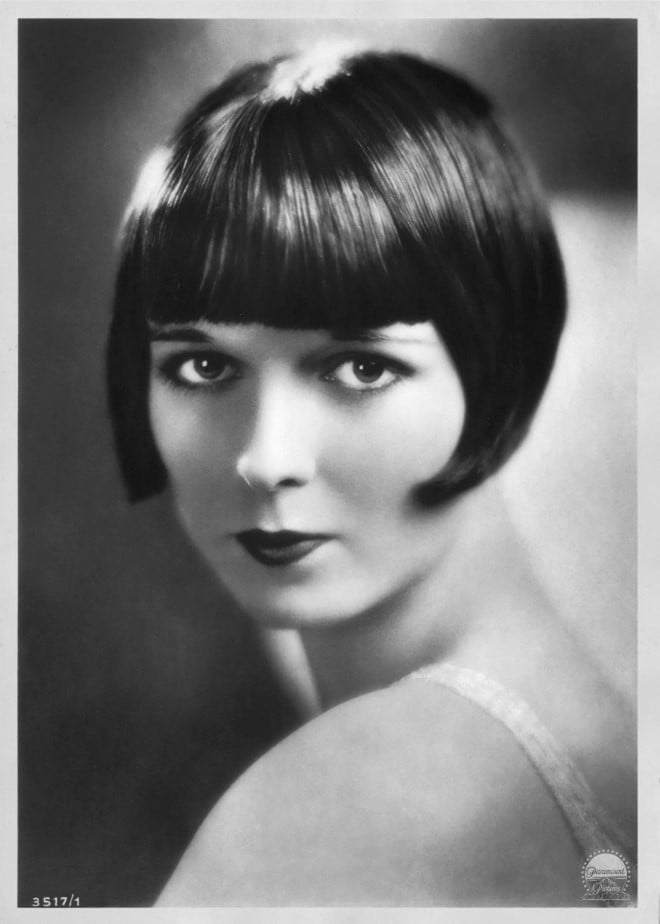

The design process for the costumes was, in many ways, an unfolding of color. Given the rooting of the production in silent film, the most natural place to start was black and white. That becomes the color palette for our heroes, Tamino and Pamina, stylized in 1920s Weimar Republic evening wear, Tamino in a tuxedo and Pamina in a black dress and bob hairdo, inspired by silent film icon Louise Brooks.

Louise Brooks, John Kisch Archive/Getty Images

Louise Brooks, John Kisch Archive/Getty Images

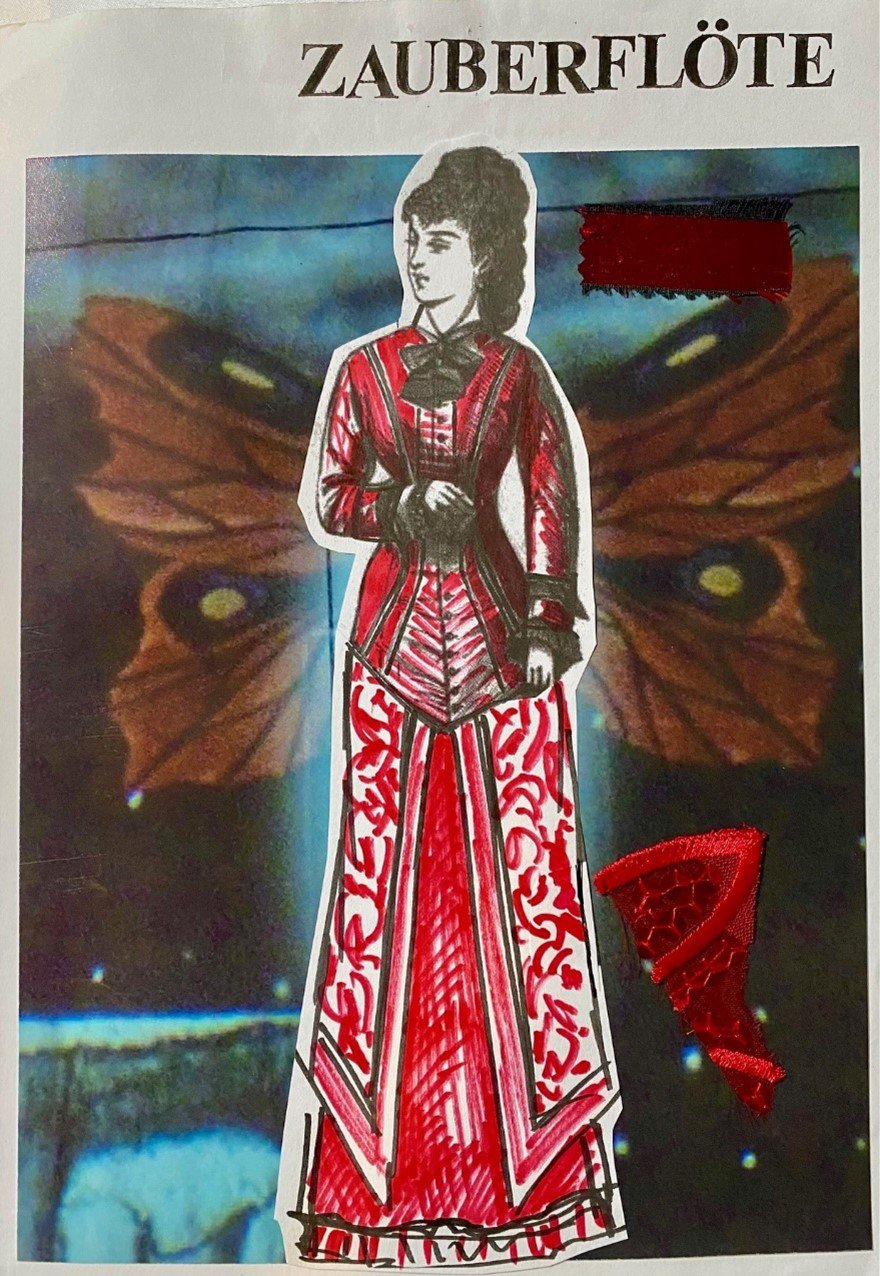

The original conception of the production morphed Pamina’s palette from black and white to color, with a red dress in Act II that almost made it to the opening in 2012 but was cut at the last moment.

Esther Bialas’ design for Pamina’s original red dress, not ultimately used in the production.

Esther Bialas’ design for Pamina’s original red dress, not ultimately used in the production.

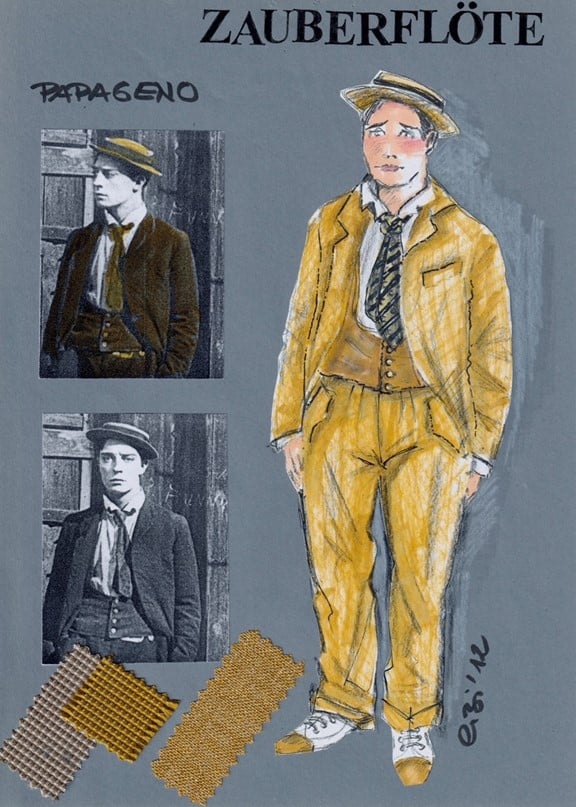

Color is rather built into some of the other costumes. Papageno is very much an outsider to the formal world of Weimar black and white, and Esther chanced upon a mustard yellow suit for him, echoed by Papagena in a feathered version in a partner color, canary yellow.

Esther Bialas’ design for Papageno.

Esther Bialas’ design for Papageno.

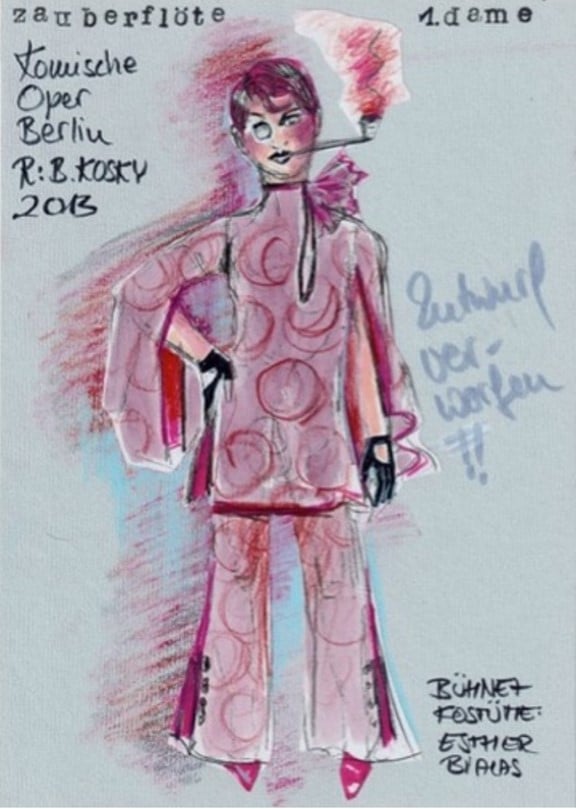

The three ladies had an interesting trajectory. The first idea was for a very sexy, seductive look but perching on a high platform was near impossible in high heels, and so the need for flats called for a different approach.

An example of one of the Ladies in Esther Bialas’ original design conception.

An example of one of the Ladies in Esther Bialas’ original design conception.

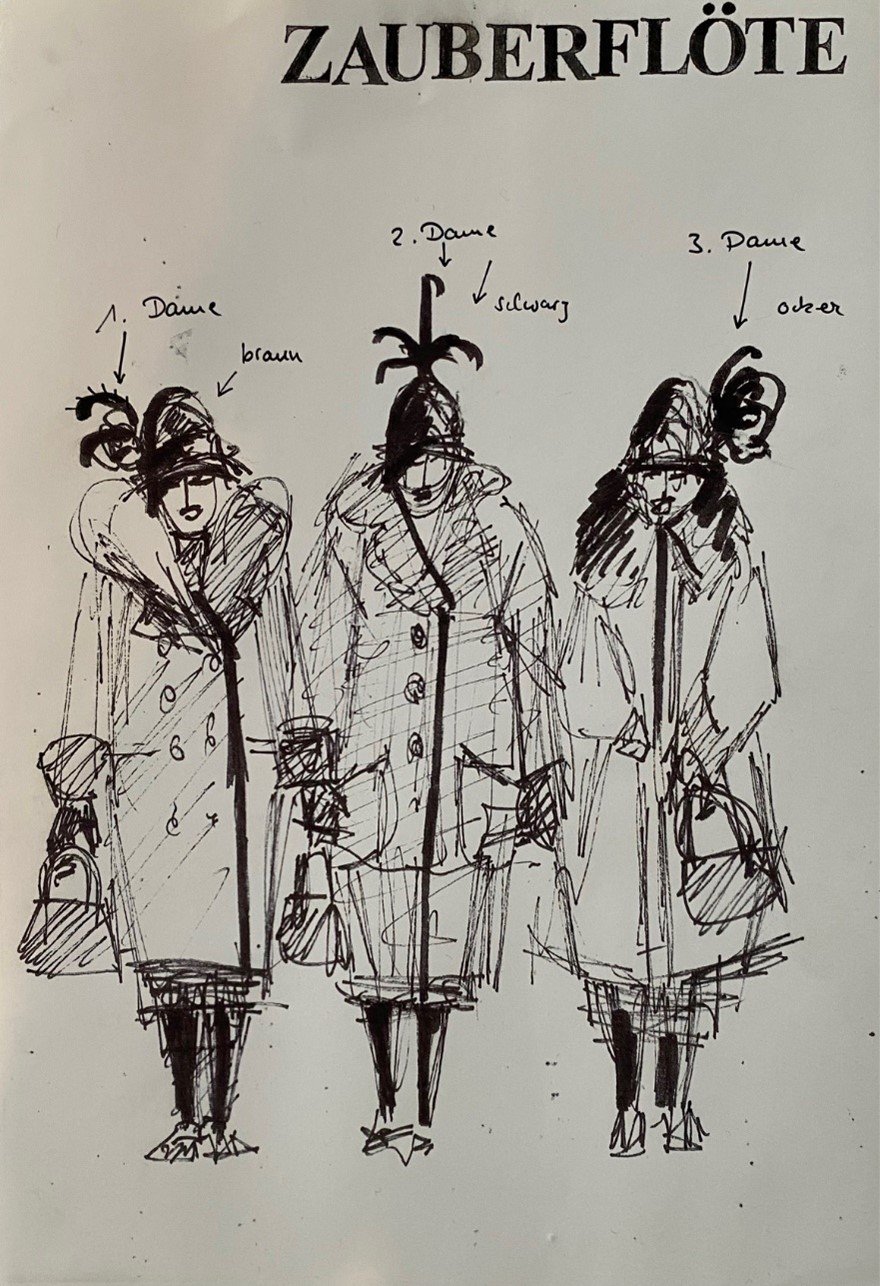

The second approach was more along the lines of something worn to clubs or the opera, but then a third idea emerged. In the canteen of the Komische Oper, Esther sketched out three older neighborly ladies with big coats and big personalities. The sketches stuck!

Esther Bialas’ canteen sketch for the Three Ladies’ ultimate design.

Esther Bialas’ canteen sketch for the Three Ladies’ ultimate design.

Olivia Smith, Ashley Dixon, and Marie Therese Carmack as the Three Ladies (photo by Cory Weaver)

For a production that is, at first glance, a big white wall, there is a huge amount of complexity and finesse needed to make this work, not only in the magic of the doors. There are two large towers downstage of the wall that house the chorus for much for the opera. The Chorus members are dressed as doubles of, at times, Sarastro, Tamino, and Pamina, and so we have to make about 46 sets of matching hair, beards, and costumes.

Multiple look-alike Sarastro beards for the Chorus

Multiple look-alike Sarastro beards for the Chorus

And then there are the prosthetics! The Magic Flute is a world of fantasy, and Barrie Kosky expresses that particularly in the characters of The Queen of the Night, portrayed here as a giant spider, and Monostatos, whose look is inspired by the film Nosferatu. I spent some time with Jeanna Parham, our head of wig and make-up, who shared with me how she and her team created these looks.

An early design for the Queen of the Night (left) next to designer Esther Bialas in a 1936 headpiece first worn by Eva Turner, and later Maria Callas for the cover of her Turandot album (right)

A close up look at Zhengyi Bai as Monostatos

A close up look at Zhengyi Bai as Monostatos

As I mentioned earlier, the production has been to some 40 opera houses around the world, and something akin to a game of telephone happened as the designs morphed from house to house. For this San Francisco presentation, designer Esther Bialas wanted to go back to the clarity of her original ideas in Berlin and worked very closely with Jeanna to ensure that the prosthetics and make-up design returned to their original conception.

Head of Wig and Make-Up Jeanna Parham and her team in the Wig Room at the Opera.

Jeanna says that one of the key things in designing a headpiece, like the Queen of the Night’s, is keeping weight to an absolute minimum, using a light polyurethane. The singer must wear the headpiece not just for the length of the opera but for the hour or so beforehand while she gets into costume and make-up, so about four and a half hours in total. A full headpiece like this can also create a feeling of sensory deprivation if it covers the full head, changing how a singer hears their own reverberations. To avoid this, Jeanna and her team have worked to ensure the headpiece is more open in the back, allowing our Queen, debuting Polish soprano Anna Simińska, not to be completely encased in the headpiece.

Anna Simińska fully made up in her prosthetic head.

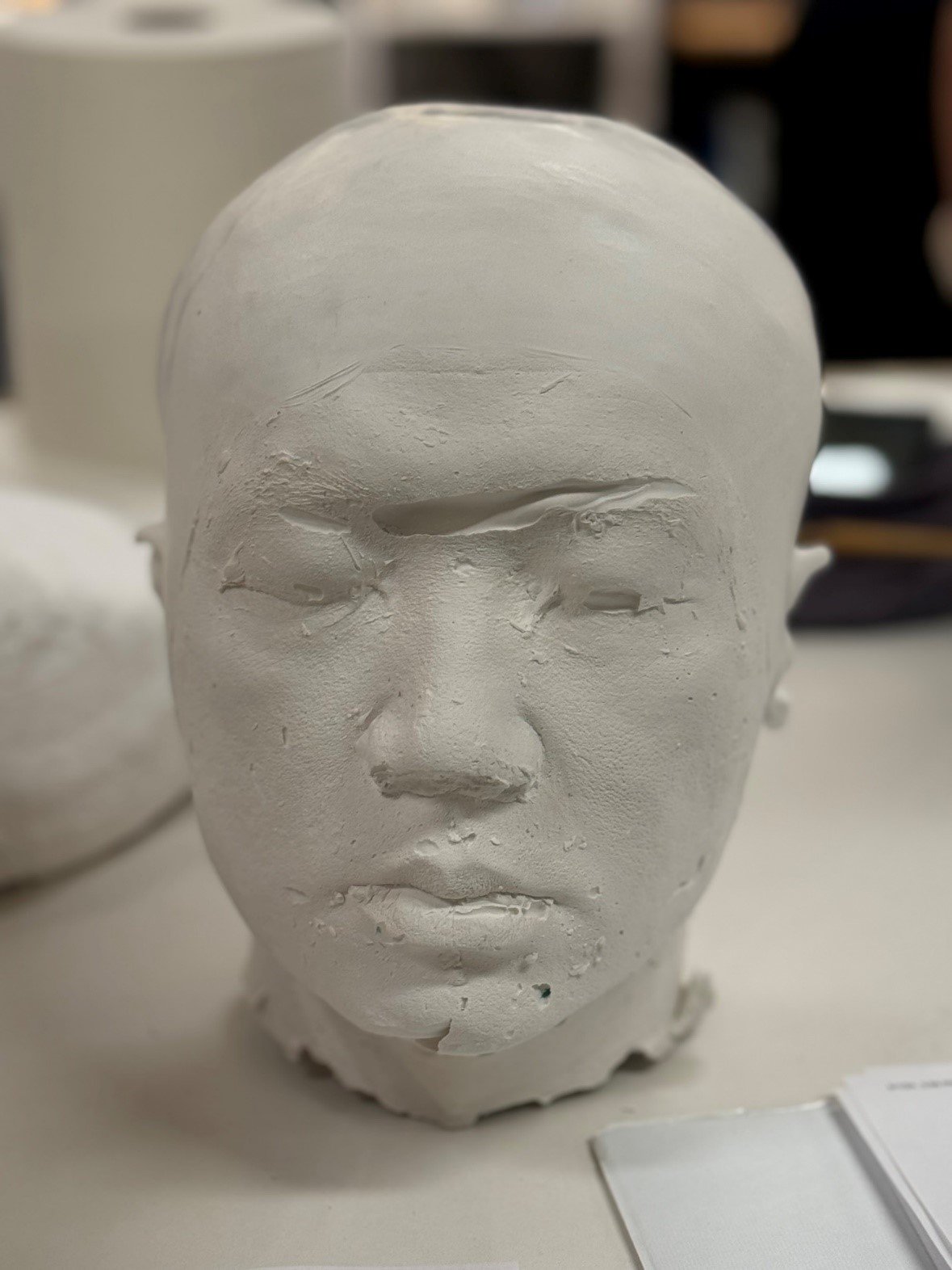

The process for both the Queen and Monostatos began by taking a silicone mold of each singer’s head. In Hollywood prosthetics, silicone replaced a product called alginate which is material similar to that used for a dentist’s tooth mold. Alginate shrinks as it dries and can only be used once. Silicone is much more flexible, and you can make a hundred different molds out of one silicone impression. San Francisco is well served for all the materials for prosthetics like this with the store Douglas and Sturgess over on Bryant Street, specializing in sculpture molding and casting.

Jeanna Parham showing the various stages of casting for the Queen of the Night’s headpiece

I have huge admiration for our Monostatos, Zhengyi Bai. His Nosferatu creation required his whole face to be wrapped in silicone and then plaster, with just two air holes for his nostrils showing. All of our make-up artists working on this have done similar prosthetic work in other contexts and so were well trained in these techniques.

Zhengyi Bai during the process of making the plaster mold of his head.

Zhengyi Bai during the process of making the plaster mold of his head.

The casting of Zhengyi Bai’s head in plaster.

The casting of Zhengyi Bai’s head in plaster.

Once the casting of the face is complete, prosthetic pieces can then be made that fit the face like a glove, although more delicate pieces like the ears require separate molding as wig and make up artist Tim Santry demonstrated, popping them out of their plaster casts when I visited the wig shop. As with the costumes, it’s imperative that the prosthetics give the singer full range of jaw motion so that their singing isn’t impeded in any way. It’s such a fine balance of form and function.

Wig and Make-Up Artist Tim Santry popping an ear casting out of its silicone mold

Wig and Make-Up Artist Tim Santry popping an ear casting out of its silicone mold

Tim Santry fitting Zhengyi Bai’s prosthetic pieces.

Tim Santry fitting Zhengyi Bai’s prosthetic pieces.

This is just a flavor of the many extraordinary layers that are going into making this Magic Flute, one of the most immersive, fantastical interpretations of the production ever created. It’s for good reason that it’s been presented all over the world, and we’re so proud to bring it to San Francisco. It’s a fabulous expression of so many artistic skills and crafts. I have a feeling that Mozart and his librettist (and the original Papageno) Emanuel Schikaneder would be delighted and enthralled by the whimsy and heart of this production. I hope that you enjoy watching it as much as we’re enjoying bringing it to life!

Photo by Cory Weaver