Backstage with Matthew: Dressing Gilead

The handmaids’ and wives’ cloaks.

We are so happy to welcome Christina to San Francisco Opera for the first time with The Handmaid’s Tale. She is an incredibly in-demand costume designer, working frequently with director Simon McBurney in both his Complicité shows and some of his opera work. When director John Fulljames approached her about this new co-production between Copenhagen and San Francisco, she had read the book years ago, but decided to avoid watching any of the Hulu series that had just come out—she wanted to ensure that her influence was the primary source of the book, not the secondary source of the television series.

Handmaid’s Tale costume designer Christina Cunningham with a variety of costumes from the production.

Handmaid’s Tale costume designer Christina Cunningham with a variety of costumes from the production.

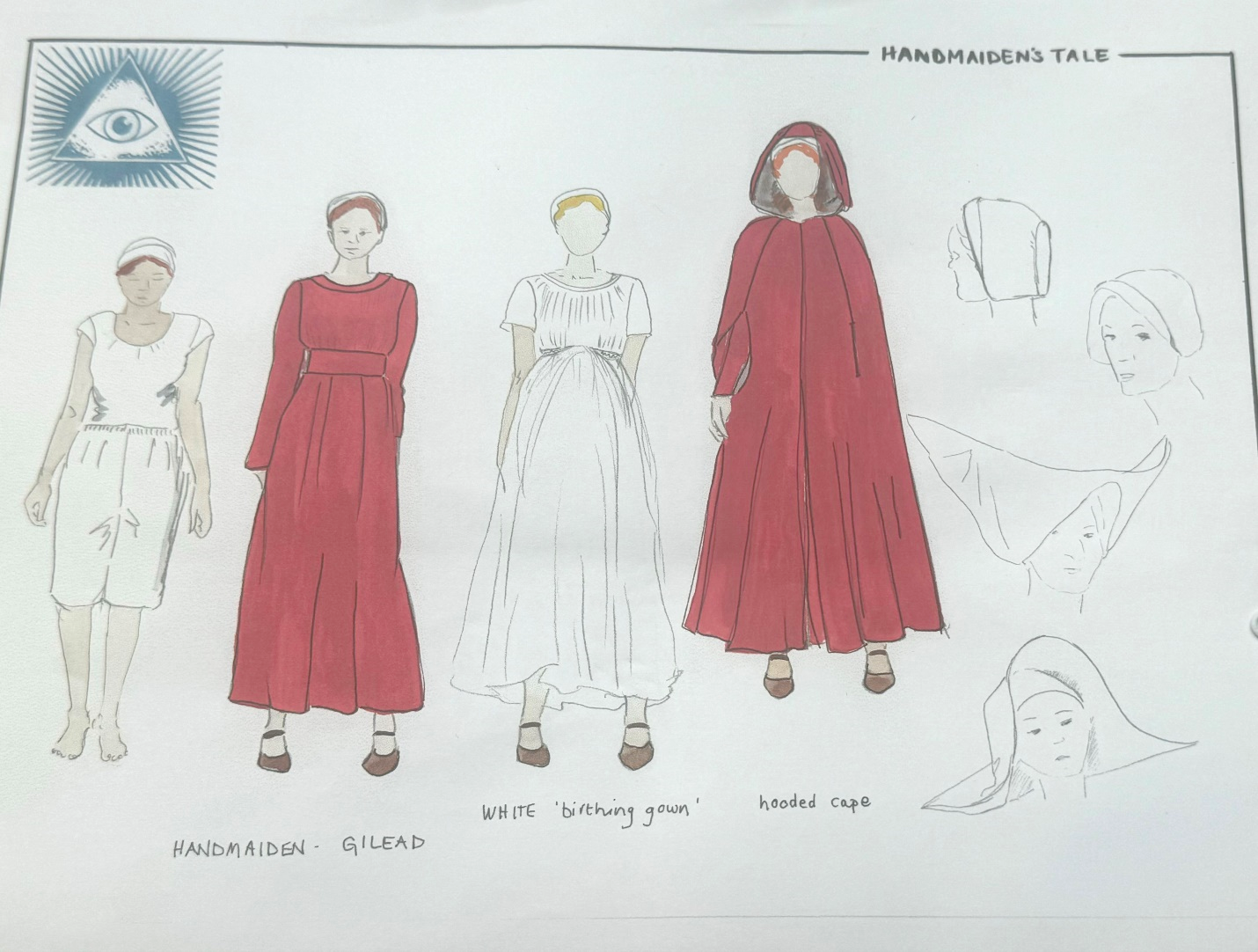

There were some fundamentals that she knew going in: first, the colors are the colors—they are part of the iconography of the piece (handmaids in red; wives in blue; aunts in green; Marthas in brown). Christina noted that this is probably the most prescriptive show that she’s ever worked on. Secondly, the handmaids’ headpiece could not cover the ears of the singers—it had to give them aural access. From there she began to envision what could be.

The costumes are not from a specific period, but generally harken back to a mid-20th century aesthetic when a patriarchal society was more fundamentally ingrained. A time when women’s clothes had a more feminine shape but were also more modest and understated. Wherever possible, Christina went back to the book. For example, Margaret Atwood talks of the Handmaids wearing a long red dress; and talks of the wives being in blue. Christina did switch the colors of the aunts and Marthas clothes: in the book the Marthas are a “dull green” and the aunts are in brown, but, as you’ll see below, Christina favored the dull green for the aunts to emphasize the military

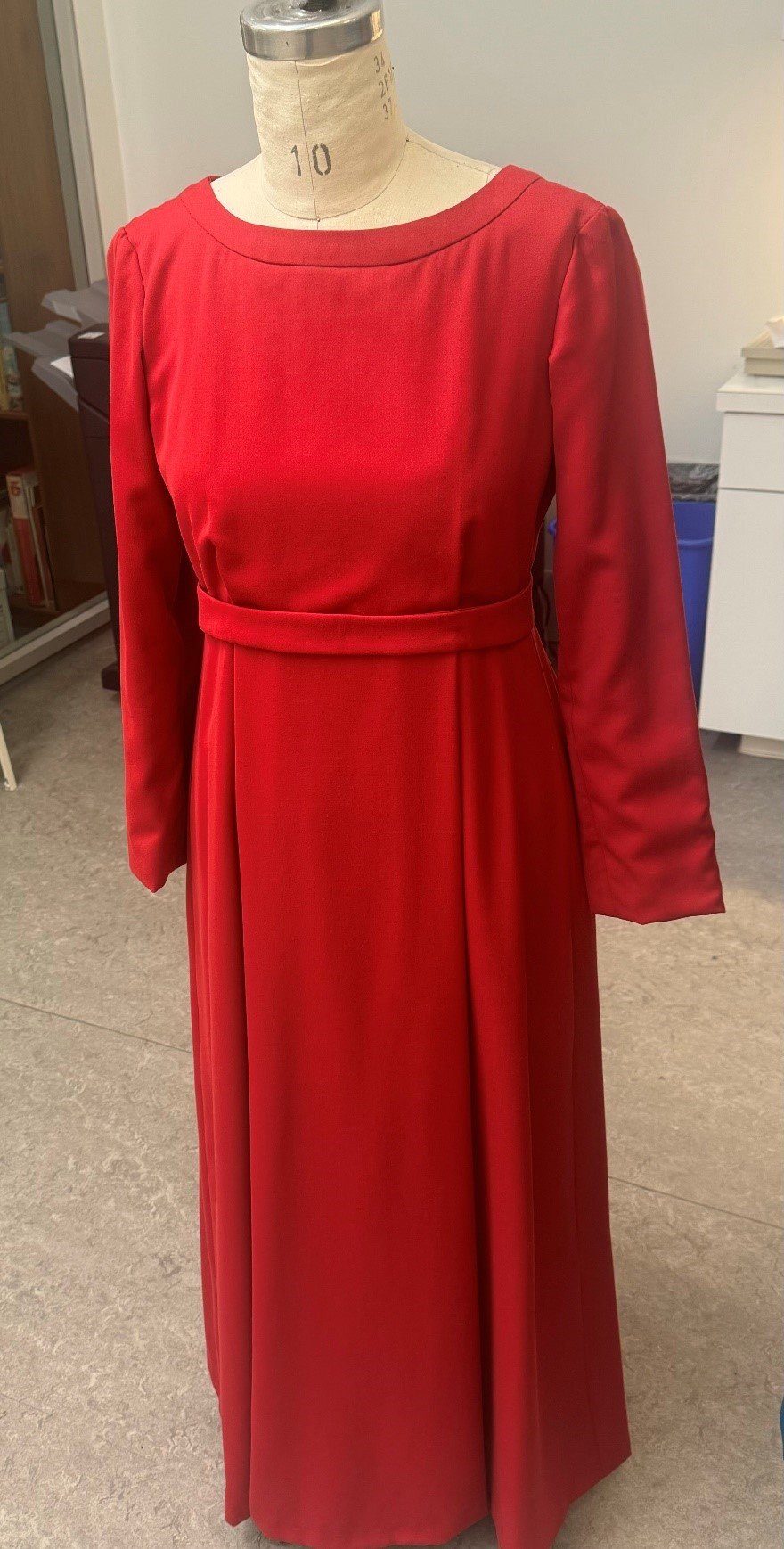

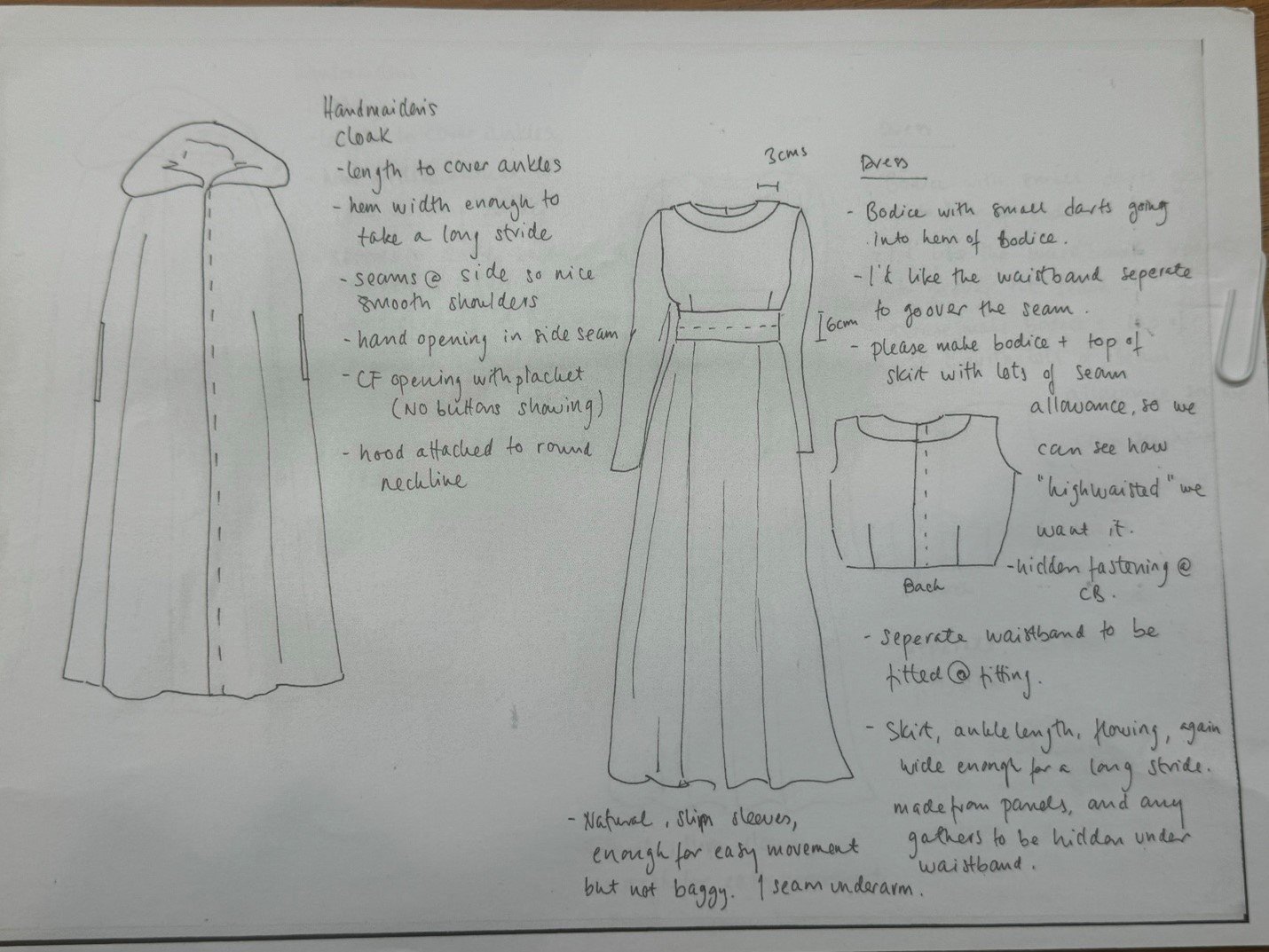

Christina wanted the handmaids’ dresses to be flattering, but reserved. She gave them a slightly more open neckline, a heavy fabric that gives a glide to the dress as the handmaids walk, and a higher waistline that can work for pregnant handmaids without requiring new dresses. In the book the handmaids are in red dresses, the color of blood. The production’s capes are made in a strong red, but Christina chose to soften the tone of the dresses, which are still red, but in a slightly muted tone, to give the subtle feel of many washes, uses, and being handed on from handmaid to handmaid.

Christina’s designs for the handmaids, and one of the dresses

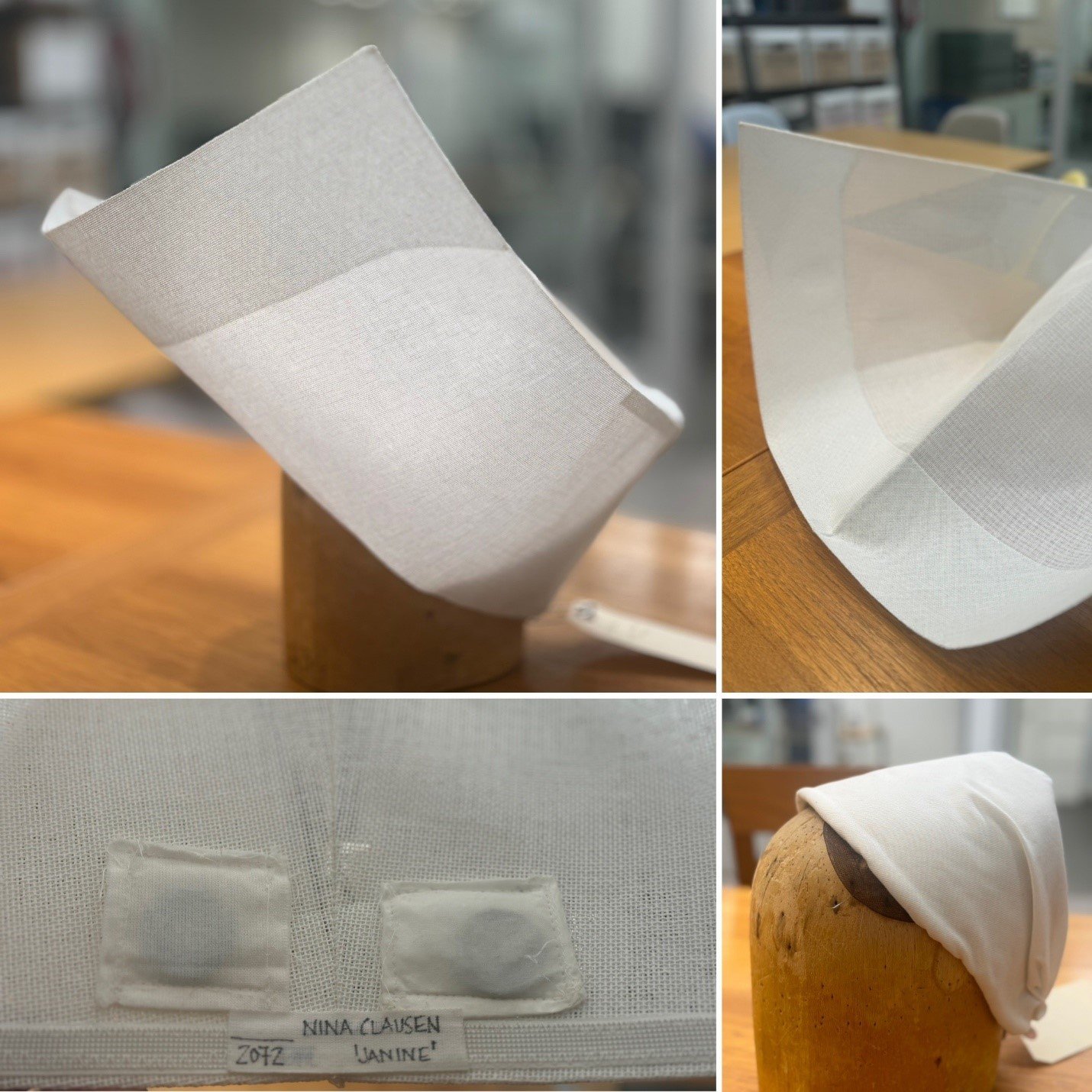

The ‘wings’ headdresses were a challenge. The book says of the prescribed white wings: “they keep us from seeing, but also being seen.” Offred describes her room in the commander’s house as “In a nunnery...time is measured by bells, and there are no mirrors.” Christina had seen images of the red and white handmaids’ uniform being used in protests in which the white wings were much more enclosing. But in an opera, the singers have to be able to hear themselves and each other, and see each other and the conductor, so she had to design them to take all of that into account.

She worked with a milliner in Copenhagen to come up with a material that’s not quite as heavy as buckram, and then worked with singers to try out shapes and sizes, to ensure that they could hear, see the conductor, and be slimline enough that they could credibly lean in and whisper to each other (important for the resistance) without hitting bonnets. To ensure the integrity of the wings, she added a folded seam on top to strengthen the edges without adding weight. As Christina notes, these headpieces take a lot of space to travel!

The handmaids’ headpiece and bonnet showing the strengthened seams and magnet system.

The handmaids’ headpiece and bonnet showing the strengthened seams and magnet system.

The handmaids also have a small bonnet that they wear when not out in public, and Christina came up with a clever magnet system that allows the main headpiece to lock onto the bonnet to ensure it’s always centered and secure.

The wives are dressed in a feminine but modest look from the 1950s, again in a slightly muted blue, and a headpiece that they wear when going out to show a little more formality. It’s as much a uniform as the handmaids in that sense.

Designs and an example of the wives’ costumes.

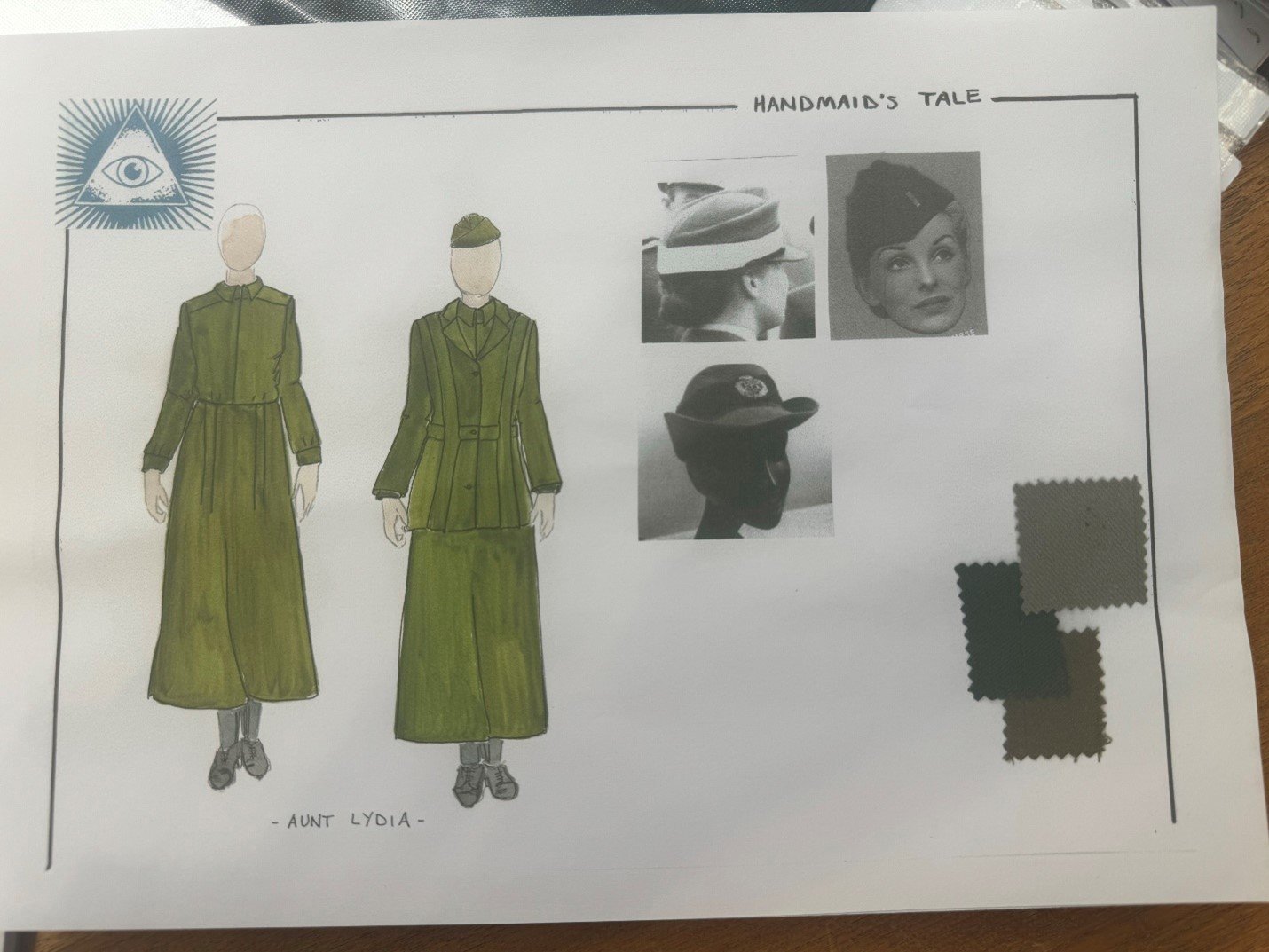

The aunts embody an element of the military and Christina turned to female military uniforms as inspiration, including a pin with the eye of Gilead.

The designs and example of an aunt’s costume, including a close-up of the eye of Gilead pin.

The designs and example of an aunt’s costume, including a close-up of the eye of Gilead pin.

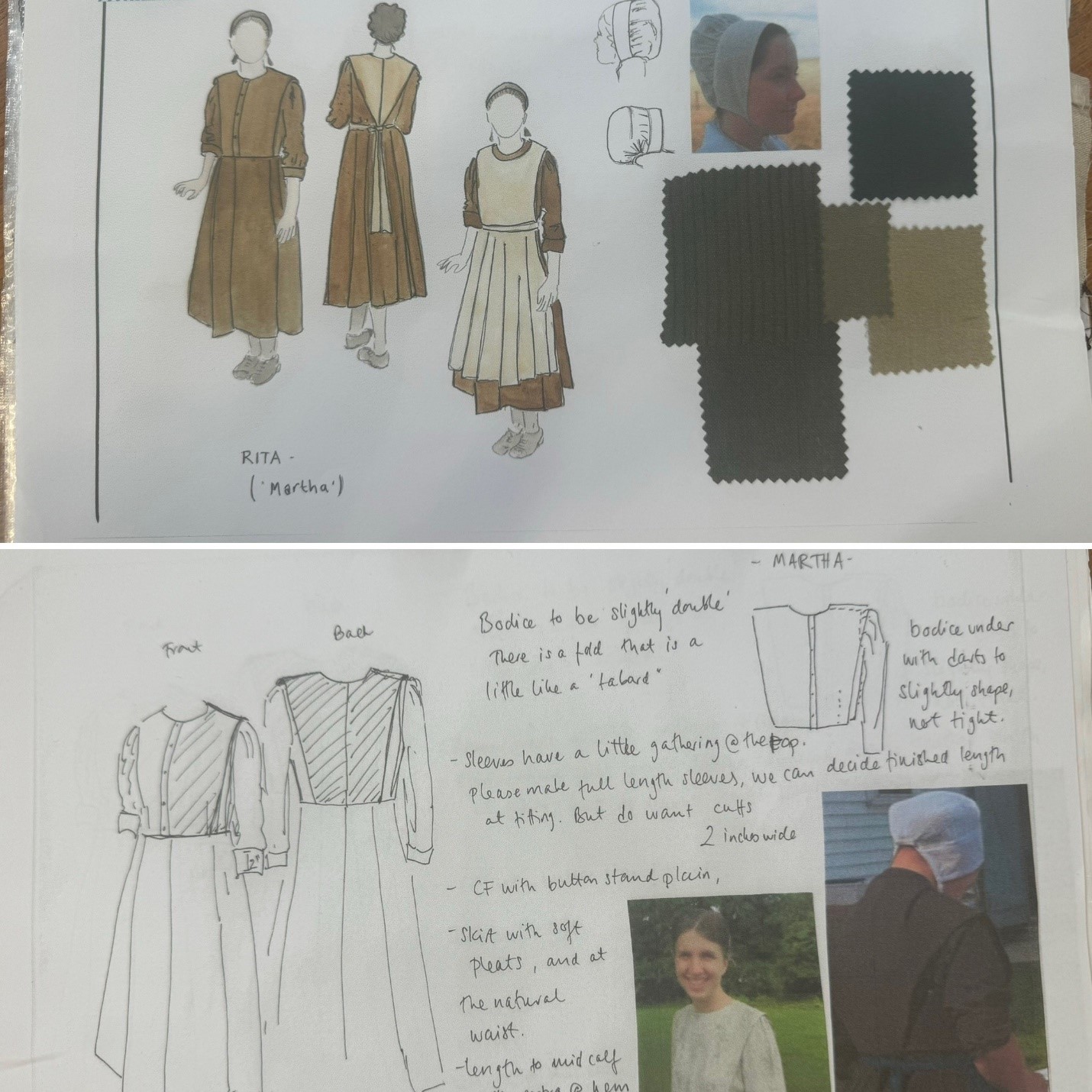

The Marthas have a more muted brown palette for their look:

For the commanders’ costumes, Christina wanted the men to feel smartly dressed but also be threatening and militaristic. She decided to go beyond the regular three-piece suit, and was inspired by the British police, using 1990s versions of the police dress uniform. Christina found a surplus supplier that provided most of the uniforms.

There are also a number of costumes from “the time before”—the pre-story, before Gilead takes over American society in a coup. These are off-the-rack clothes aimed to show the normalcy of society before all of this unfolds. These scenes feature a number of children, and Christina shared a Covid-quirk. The production was originally intended to be produced in Copenhagen and San Francisco in 2020. When it came back to Copenhagen in late 2022, there was a Danish requirement that those people originally cast be offered the job again, including the supers. Those children cast in 2020 had outgrown their costumes and so Christina and the team there had to adapt and adjust.

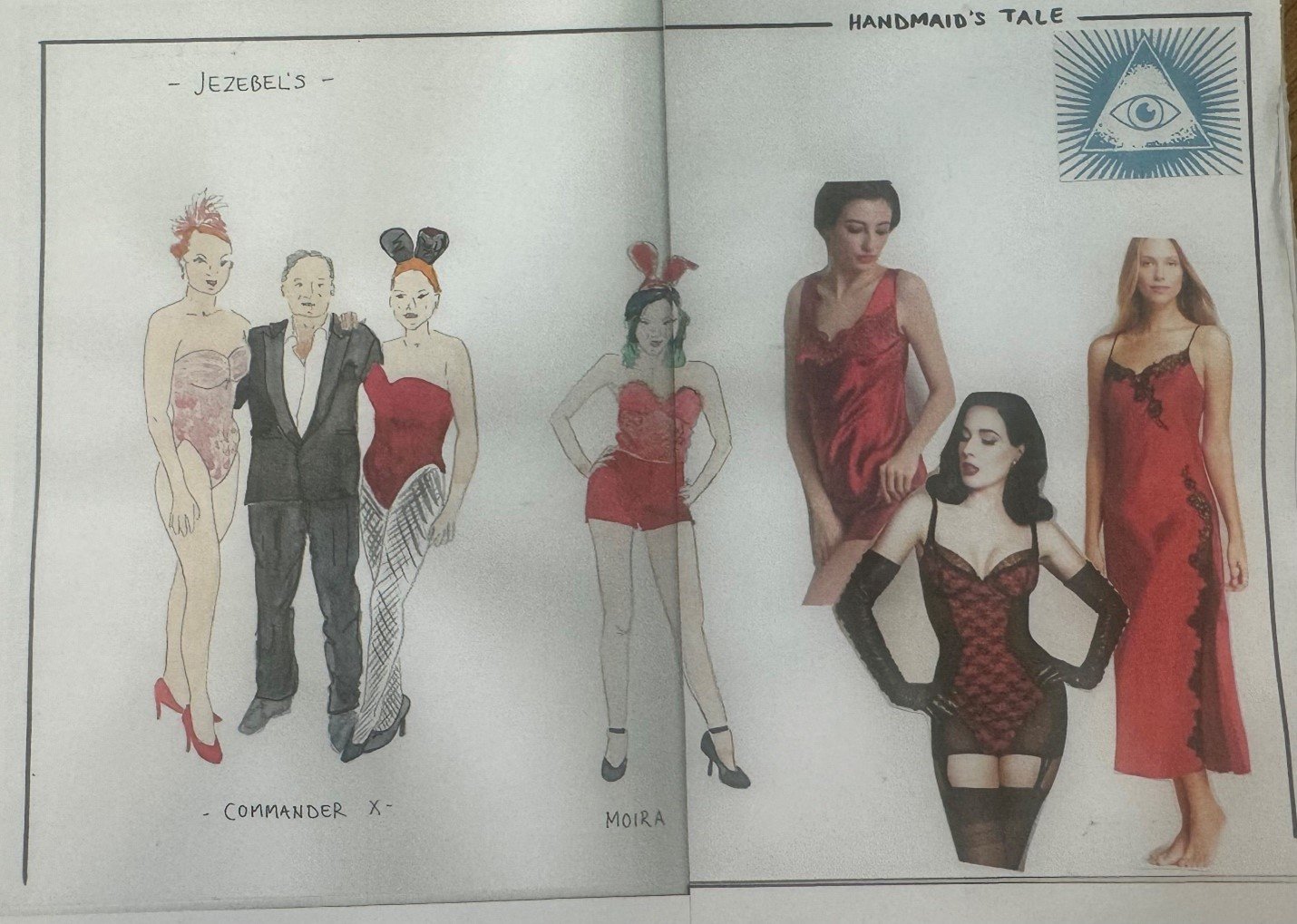

An interesting cross over from the time before to present day Gilead happens at Jezebels— the nightclub that the Commander takes Offred to in the second act. Here the ladies entertaining the commanders are in clothes of the time before, but it’s as though they’ve found mismatched items from a dressing up box left up in an attic somewhere—things that the commanders have squirreled away from the time before and that they’re making the ladies wear.

In a production with this much uniformity in the costuming—big blocks of commonality on stage—the costume production must be on heightened awareness to the smallest of details. Seams, colors of fabrics, shades of white—all of these things have to maintain an absolute uniformity, otherwise the audiences’ eyes will focus on the differences not the commonalities, particularly when set against Chloe Lamford’s clean white set (a note that Chloe was also the designer of Innocence just on stage in June).

The handmaids’ and wives’ dresses.

It's fascinating to see how Christina has fashioned this production, always sensitive to the text, but ensuring the practicality of the costumes on stage to both tell the story, and to allow the singers the freedom to perform within the restrictions of their Gilead uniforms. I can’t wait to see this come to life on stage in just a few weeks, and to share it with you in September.

As we look forward to a new season, I also wanted to invite you to reflect back on the incredible season just closed and, if you feel moved, to nominate us for the International Opera Awards. Nominations close on July 31, 2024 and there are a variety of categories including conductors, singers, productions, orchestras, choruses, designers, directors, rising stars, etc. San Francisco Opera was shortlisted as “Opera Company of the Year” last year, and we’d love your help in celebrating the best of the best from the last season. So please do take a moment and nominate your favorites from the 2023-24 season. The more nominations we get the stronger our chances! The link is here: www.operaawards.org/nominate/.

Thank you for making the 101st season of San Francisco Opera such an extraordinary one. Here’s to 102 just around the corner!

Christina’s design sketches for the handmaids’ costumes.

Christina’s design sketches for the handmaids’ costumes.