Backstage with Matthew: The Music of Conversation

The continuo was a very important feature of baroque music (around 1650-1750). It began as the basso continuo or continuous bass and was a way of underpinning the harmonic essence of a piece of music through a strong, rhythmic and propulsive bass line that was usually led from the harpsichord or organ, but that could be embellished through other instruments like a cello, bassoon and theorbo (or arch-lute). The continuo featured almost like a conductor, defining form, structure and rhythm. The continuo remained in use through the operas of Haydn and Mozart and, in a few cases, into some operas of the early 19th century like those of Rossini. However, the harmonic energy of the whole orchestra was, by the 19th century, beginning to render continuo unnecessary, so pieces like The Marriage of Figaro are some of the last to use the practice.

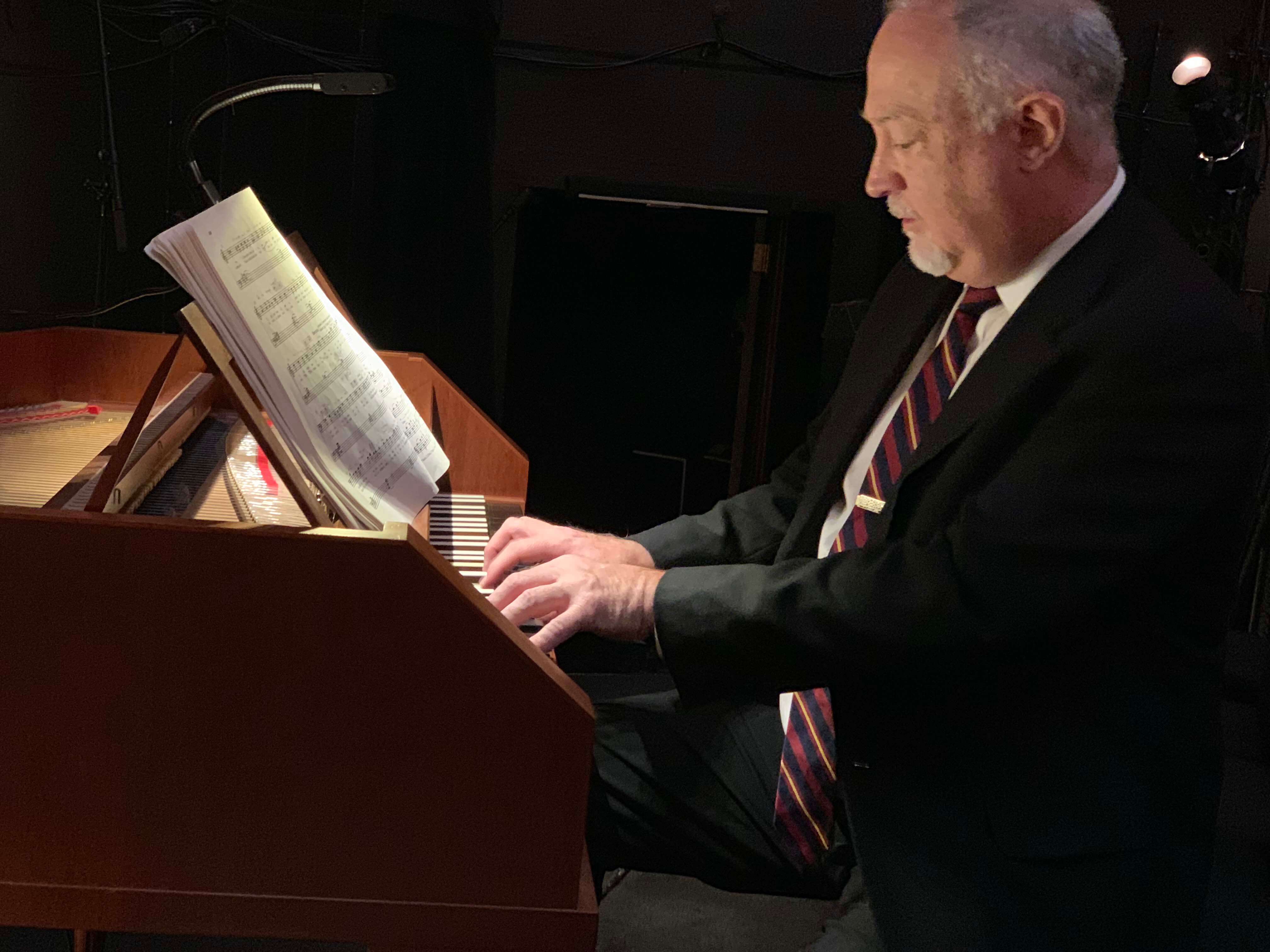

The Figaro continuo is played by Bryndon on a fortepiano – an early precursor to the piano with a similar mechanism but a more delicate sound. There is also a cello accompaniment, played by our Associate Principal Cellist (and Principal on this production), Thalia Moore, but it is only used before one aria (‘Se vuol ballare’ – skip ahead to 1:50 on the Spotify link). Thalia does a little choreographed move in the pit moving from the center to the side, unseen by the audience!

We’ll get back to the fortepiano in a moment, but let’s talk first about how the continuo is used in opera. Baroque and classical opera exists very much as a series of individual moments – “numbers” that define a discrete piece of stage business or emotion. As you may have heard in pieces like Figaro, these numbers alternate between different types. There are the emotive arias that allow us to dwell on a particular moment. There are exuberant choruses that punctuate the action. And then there are the recitatives – the moments of conversation between characters. These are fast-paced moments with a lot of back and forth and not much melody. They allow us to move quickly from A to B and allow the story to make a modicum of sense! And recitatives are typically accompanied by…the continuo!

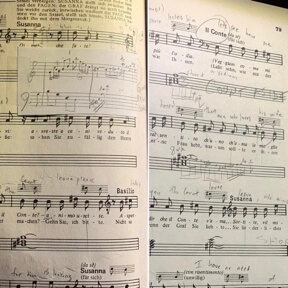

Thinking of recitatives as conversations is helpful in understanding the very unique nature of continuo. Although the music and text of the conversation is written by the composer and librettist, the exact delivery isn’t. It’s much more free-form than an aria. The specific rhythms, timing, emphasis, etc. is up to the singer and can change from performance to performance. This means that Bryndon has to be completely alert and in-tune with what is happening onstage, responsive to it in a heartbeat. You may notice that the conductor doesn’t conduct the recitatives. This is because it is unfolding real-time between the singer and the continuo. Bryndon estimates that 85% of his work in an evening is really left to the moment. There are a few moments that he will keep constant – moments where specific music is needed for a dramatic moment on stage for example – but the rest of it is very fluid and responsive. The composer gives a harmonic framework and indicates how long the keyboard player should remain in that harmony, but within that envelope, it is up to Bryndon to determine how to play the harmony. (In the Baroque era they wouldn’t even give a chord, just a bass line and then numbers above the bass note to indicate the harmony, e.g. 6-5 to indicate that you play a chord five and six notes above the bass, hence the term “figured bass.” By the time of Mozart, full chords were being written out.)

Bryndon sees his role very much as providing the emotional underpinning for the vocal conversation. His is the subtext that otherwise exists in the orchestra. He may “roll” chords which is when he’ll play something of an arpeggio, going up and down the harmonic chord – that gives a more full, sustained sound. For more incisive interactions on stage he’ll play shorter, more clipped chords. And if it’s a moment of dastardly action, he might even play some dissonant tone clusters in the bass that sound more like percussion than anything else. And, when it’s appropriate, he’ll even add some little musical references that help underpin the text.

These little musical references are the hidden secret language of the continuo player and are where they get to have a lot of fun. Bryndon tells me that in more serious operas (like La Clemenza di Tito by Mozart), you really have to keep things very strict and formal – to be playful in the continuo would be at odds with the spirit of the piece. But in lighter Mozart like The Marriage of Figaro, you can weave in some musical jokes and references. For Mozart, Bryndon generally keeps these little musical references limited to other Mozart music – he feels that even the recitatives are so perfectly constructed that only the music of Mozart can be incorporated. He may use something taken from opera itself – for example Bryndon’s continuo at the start of Act III is actually a reworking of the overture, put into the lower register and in a minor modality. Or he will interpolate references from another piece of Mozart – he’s using a number of the violin sonatas in this Figaro. He did let me in on one non-Mozart that he’s snuck in: for the entrance of Don Basilio, he wanted something flamboyant and fanciful, so he’s quoting Mendelssohn’s Spring Song.

Now, in Rossini’s operas it’s a whole different story. Bryndon is much more willing to pull from any source material for Rossini recitatives, and his musical embellishments. He might use a little bit of a Richard Strauss tone poem, a little Wagner, or even go outside the classical world. When he played continuo for The Italian Girl in Algiers here, he was known to sneak in a little bit of Dizzy Gillespie’s A Night in Tunisia! Bryndon tells me that these musical references are particularly fun for the orchestra who are not playing during a recitative and can play “guess that tune” as he interweaves these musical references. He mentioned that one of our viola players had asked him to try and get a Tristan referenceinto Figaro. He showed me how it could be done, but wasn’t sure if he was going to push the Mozart recitatives that far!

Bryndon began with us in 1990 on the music staff – he also coaches and accompanies rehearsals in addition to playing continuo. He didn’t have a continuo background but was assigned to play continuo for The Italian Girl in Algiers in 1992 with Marilyn Horne. As someone who hadn’t played continuo before, he was understandably nervous! The conductor’s preference in that production was for pretty sparse continuo accompaniment but when Ms. Horne arrived, she expressed a desire for much more elaborate continuo. More elaborate continuo it was! After he played a rehearsal with her, the great mezzo sent him a note saying “A harpsichordist is born! You’re going to be good!”

Bryndon also spent a lot of time in those early years going into schools with Adler Fellows in a program where they had to improvise an opera. He says that after years of doing that and improvising things on the spot, particularly creating music to support emotion, playing continuo became much more straightforward! He has done a considerable amount of continuo work here, mainly in Mozart and Rossini, on both harpsichord and fortepiano.

Let’s return to the fortepiano – the early precursor of the pianoforte (amazing what a simple rebranding will do!). Mozart continuos can be on either fortepianos or harpsichords – both were in use during his life. The Opera’s fortepiano comes from Paul Poletti, who made this instrument while still in Berkeley. He now lives in Barcelona where he builds, restores and teaches.

There is a single keyboard and, unlike the harpsichord, the tone varies based on how heavily you depress the keys (like a piano). The keys are a similar size to a piano key, but are much lighter in how they operate, and so Bryndon typically comes and plays for a while before a performance just to acclimate his fingers to the instrument. And, like a harpsichord, it needs to be tuned often – not just before each performance, but during each performance as well. What is interesting about this particular instrument is that the fortepiano ‘pedals’ (used to sustain notes, or make the instrument very soft) are controlled by little knee levers – so a little pre-work is necessary to get the knee coordination down!

So, in the more conversational moments in Figaro, it’s not just a conversation between the singers, it’s between the singers and Bryndon as well. He’s creating the harmonic and stylistic framework for what they’re singing. And because Mozart and Da Ponte are fiendishly clever, that harmonic and stylistic framework can change on a dime, and frequently does. There are huge amounts of recitative in Figaro making it a tour de force role for Bryndon, one which he always undertakes with spectacular skill and partnership for the singers on stage. And, if you chance to hear a little Tristan in one of the performances, you’ll know that the viola player prevailed and will no doubt be smiling!