Backstage with Matthew: The intertwining of history and fairy tales

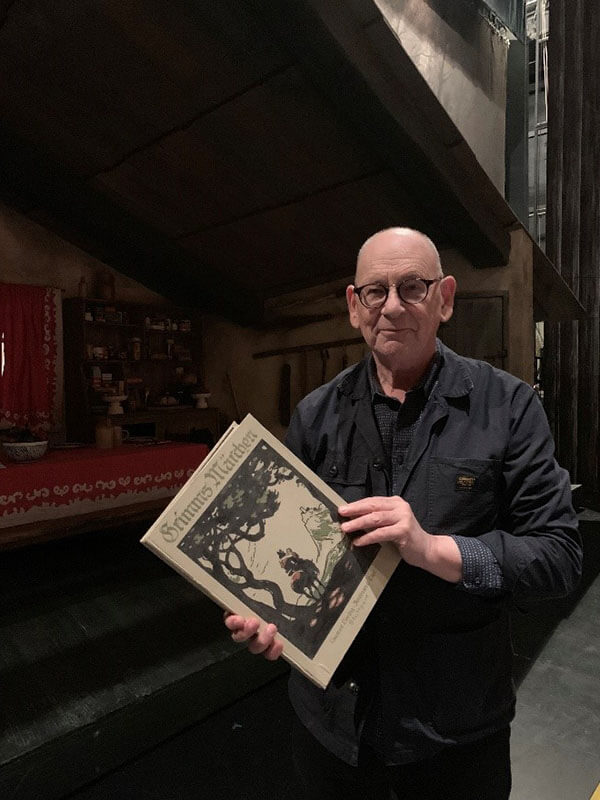

Our new Hansel and Gretel is a coproduction with the Royal Opera House in London and, in commissioning the production, their Director of Opera, Oliver Mears wanted something that was family friendly, visually magical, and very accessible. The opera has seen a wide variety of interpretations over the years, but, for this, Antony McDonald wanted to look at the work through a historical Germanic setting, fully embracing its origins in the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, and rooting it in a pastoral German setting at the turn of the 20th century. Antony has a strong interest in German and Austrian history and he drew upon a number of source materials in shaping the visual references, costume designs and social references:

- The series of German films, “Heimat,” about life in Germany through the lens of a family in a small town in the west German area of Rhineland. This was one of the first times that a non-German audience had been exposed to the history of Germany through the eyes of Germans.

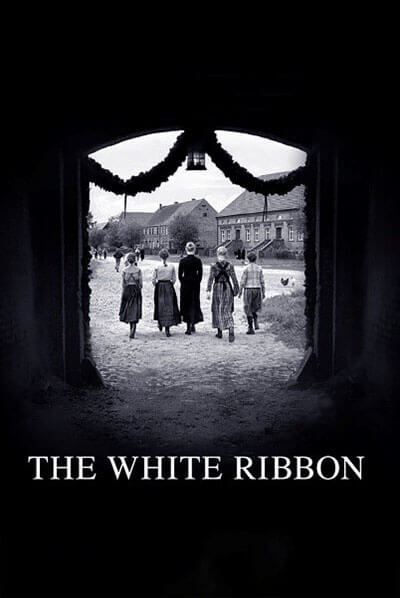

- The 2009 German film “The White Ribbon” by director Michael Haneke, depicting a family in rural northern Germany just before World War I.

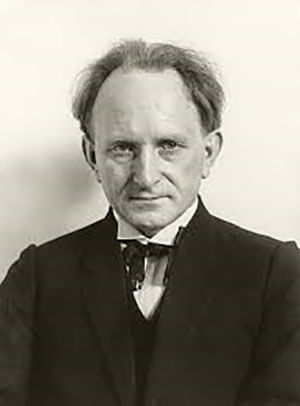

- The collection of photographs by August Sander, documenting a broad cross-section of German society in his series People of the 20th Century in which he chronicled all strata of society from princes to farmers to homeless people. His portraits give an incredible level of detail, not only in the portraiture but also in the settings.

August Sander: Self Portrait

A beautiful Taschen book about Germany around the turn of the 20th century. From this came inspiration for the beautiful Alpine show drop that you will see when you enter the theater and that punctuates each of the acts.

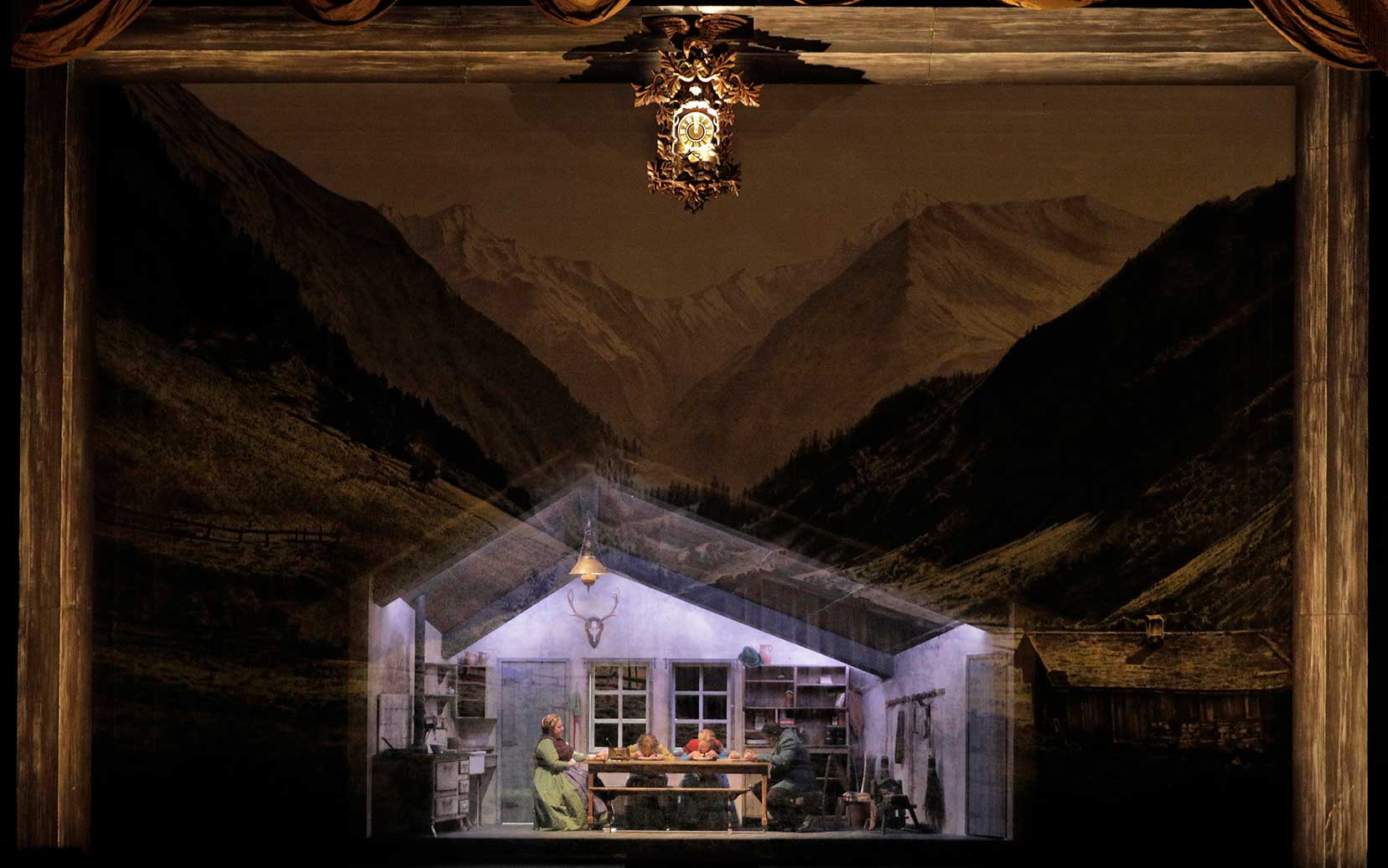

The Hansel and Gretel show drop featuring a stylized painting of a turn of the century German mountain cottage, inspired by imagery from that period. (Note the fabulous cuckoo clock that frames the opera throughout!).

- And then the source material of the Brothers Grimm -- the characters, hopes, and fears that come through in so much of their work. We saw in the last Backstage with Matthew how Antony incorporates characters from other Grimm fairy tales into Hansel and Gretel – the likes of Little Red Riding Hood, Snow White, and Rapunzel. This creates an incredibly grounded sense of tradition and magic that makes Act II in particular reach deep into our collective sense of childhood.

- The forest is an incredibly important part of both the story and the design, and the production features a very clever interplay of dimensional trees and some exquisite painted drops. The combination of the two makes for a wonderful dimensionality and evocative feel while allowing stage action to happen seamlessly within the forest.

Antony notes how important the localized nature of forests is to the myths and legends that grow up around them. Germanic forests are predominantly pine (or, as here, silver birch) and trees tend to be densely populated and the forests very dark and foreboding. As such, many of the myths that have been passed down about German forests tend to be dark and scary (like the stories of the Brothers Grimm). On the other hand, English forests with their broad, expansive oak trees, tend to be full of much more light, leading to more positive forest myths such as Robin Hood! This is a topic explored in Simon Schama’s influential book, “Landscape and Memory.” The photography of American artist Gregory Crewdson was also an inspiration in these designs.

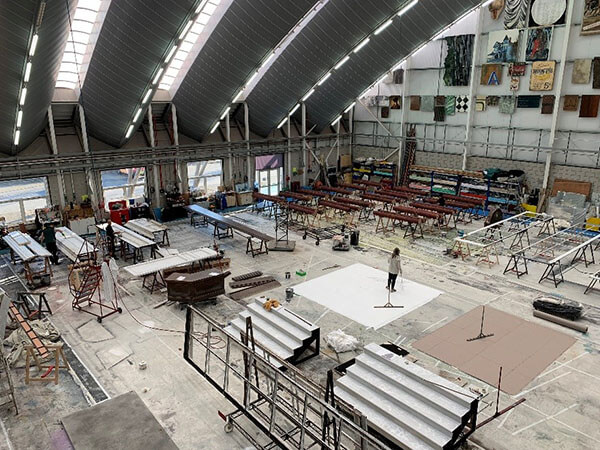

These forest backdrops, as well as the show drop, were painted at the Royal Opera House scene shop in Thurrock, just to the east of London. It’s an incredible purpose-built facility which I had the pleasure of visiting last December. Although some of their scenic painting is done on the floor, as we did for our recent Marriage of Figaro backdrop (scroll down 2/3 of the way through this backstage article to see the techniques), the Thurrock facility also features a paint wall which allows scenic painters to paint vertically and shine light through the drop to better get a sense of the final effect. You can get a sense in these photos I took last year at Thurrock of the flat paint floor and the frame for the vertical paint wall.

All of the design references and inspirations come together both in the aesthetic feel of the production as well as in the specific details. The parents’ house in Act I has an asymmetry to it that is not uncommon in Germanic rural houses of this period (and books of old German architecture came in handy here). A second forest drop sits just behind the house to create a feeling of immersion in the woods, and Antony intentionally chose to make the scale of the house focused and intimate to give a sense of the limited resources of the family.

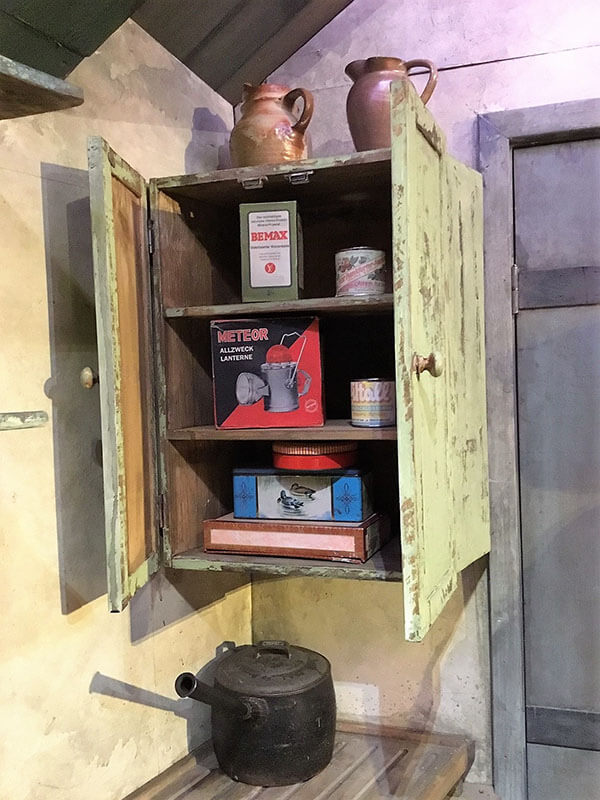

Antony, working with his creative team and the scenic and props teams at the Royal Opera House utilized a mixture of found objects and created pieces within the house to give an authentic feel. The table and benches are original pieces, found in an antique market in England; the broom-making device is manufactured by the Royal Opera based on research materials, as are the stove and the light fixture.

Food tins and boxes that sit on the shelves at the beginning of the opera (when the family is depicted in a more affluent state) are taken from original German food packaging, and recreated by the Royal Opera House props crew, while the real food that is used in the production harkens back to German staples like Sauerkraut (and of course a good helping of cakes and cookies!).

Much of the production was conceived using a model box of scale 1:25, allowing experimentation of scenery, painting, and lighting before the full production was built. Here’s an example of the early stages of the model box process, showing what we call a “white card” rendering — a three-dimensional miniature version but without the color and detail.

Antony grew up in Weston-super-Mare — a seaside town on the western side of England, and somewhere my family would often holiday when I was growing up! His parents were not in the world of theater, but listened to a lot of music, and supported his interest in seeing plays in cities like Bristol. He knew early on that he wanted to direct, and he began his theatrical training at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London, before studying in Manchester alongside the likes of Tim Albery (who directed our Arabella last year) and Julie Walters.

Antony went on to be an assistant director at Welsh National Opera’s theatre/education program in which they were developing a more European model that integrated theater and opera together. It was there that his exposure to opera really blossomed, working with directors like David Pountney, as well as designers like Maria Björnson. From there he undertook a one-year Motley Theatre Design course, then run out of English National Opera. The course was started by a British designer Margaret “Percy” Harris, and it focused on the intersection of all forms of design, always in support of the dramatic needs of the piece.

Coming out of the Motley course, Antony drew upon his connections from Welsh National Opera and headed up north to Glasgow’s Citizen’s Theater which was doing incredibly cutting edge and often controversial work. There, several artists were creating work wearing both hats of director and designer. Antony realized that this combined role was a viable pathway forward and directed/designed Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party for Glasgow. The play was seen by Richard Armstrong who was at that time running Scottish Opera, and he invited Antony to come and direct/design Samson and Delilah for them.

Antony works both as a designer with other directors (people like Tim Albery and Richard Jones who ironically directed our last Hansel and Gretel in 2002, but with a different designer), but also undertakes work as a director/designer. Although you might think it easier in a way to be wearing all the hats and making all the decisions, Antony notes that you have to be careful as a director/designer to check yourself. You have to ensure that you have good associates and confidants with whom you can test ideas, giving you some of the iterative give and take you get when working as a team.

It’s fascinating to see the depth of influences behind a production like this – the historical references, the photographic inspirations, even the sociology of different types of forest. All these layers come together to create a world onstage that draws us into the magical fairy tale world of Hansel and Gretel. We’re now up and running and I do hope that you can come and experience this beautiful fairy-tale world on our stage and see for yourself how all these influences have come together.