Backstage with Matthew: The Art and Science of Fabrics

While the last backstage blog looked at what will be the constant of the journey—The Great American House—this edition explores the element that will most propel us forward through time, and differentiate each piece—the clothes. Through the design of the clothes, we will experience the world of early revolutionary America at the birth of democracy; the high-energy sports fashion of a 1930s pre-war country club; and then a dystopian world of 2090 in which society has regressed into a foraging wasteland. The journey through clothing will be extraordinary.

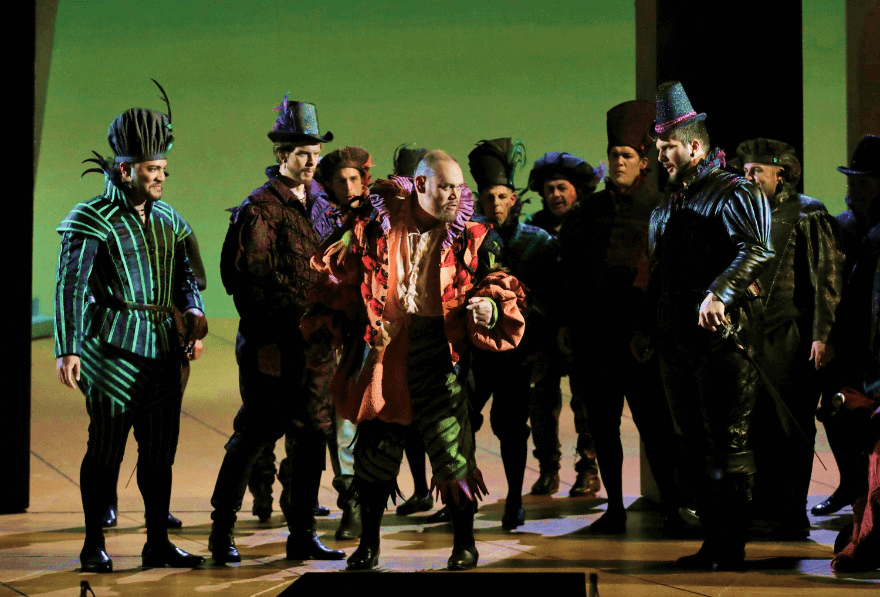

We are privileged to work with one of the great American costume designers, Constance Hoffman. You’ve seen her designs most recently on our stage in our striking production of Rigoletto. Her work is seen all over the world, and she works extensively in all theatrical forms.

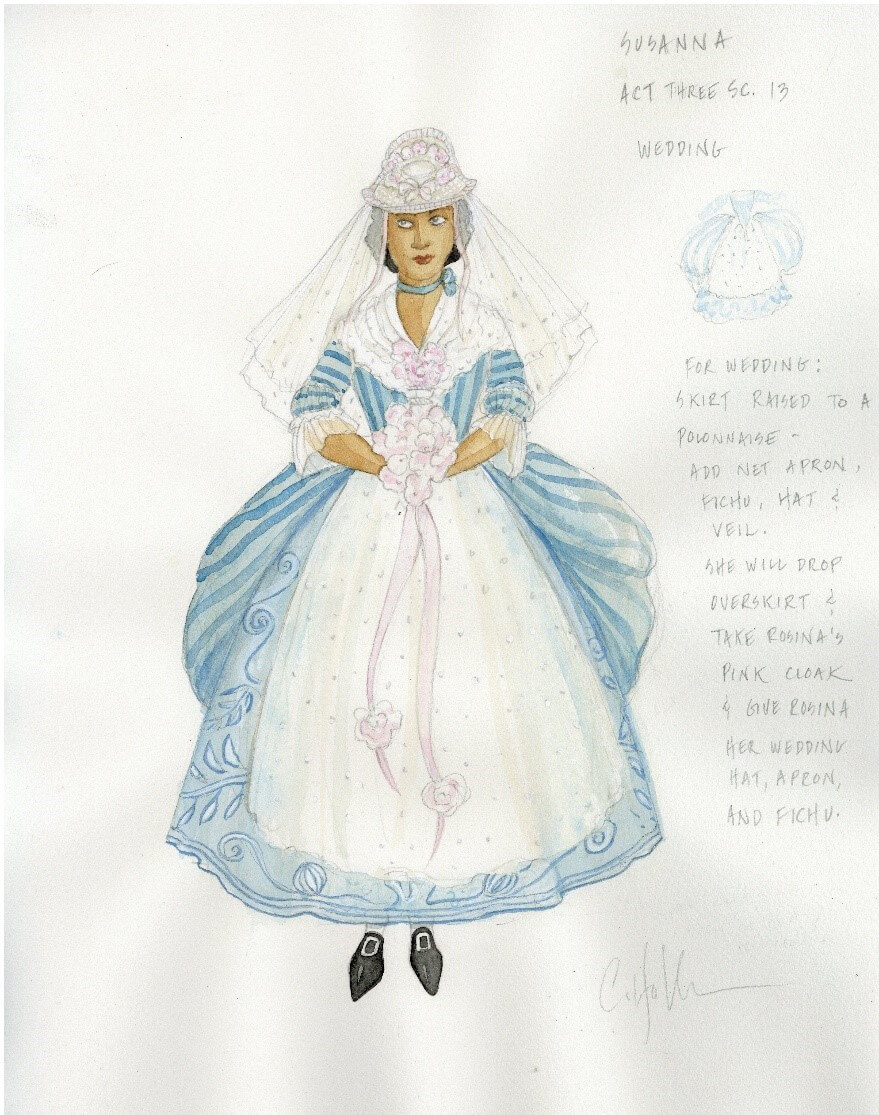

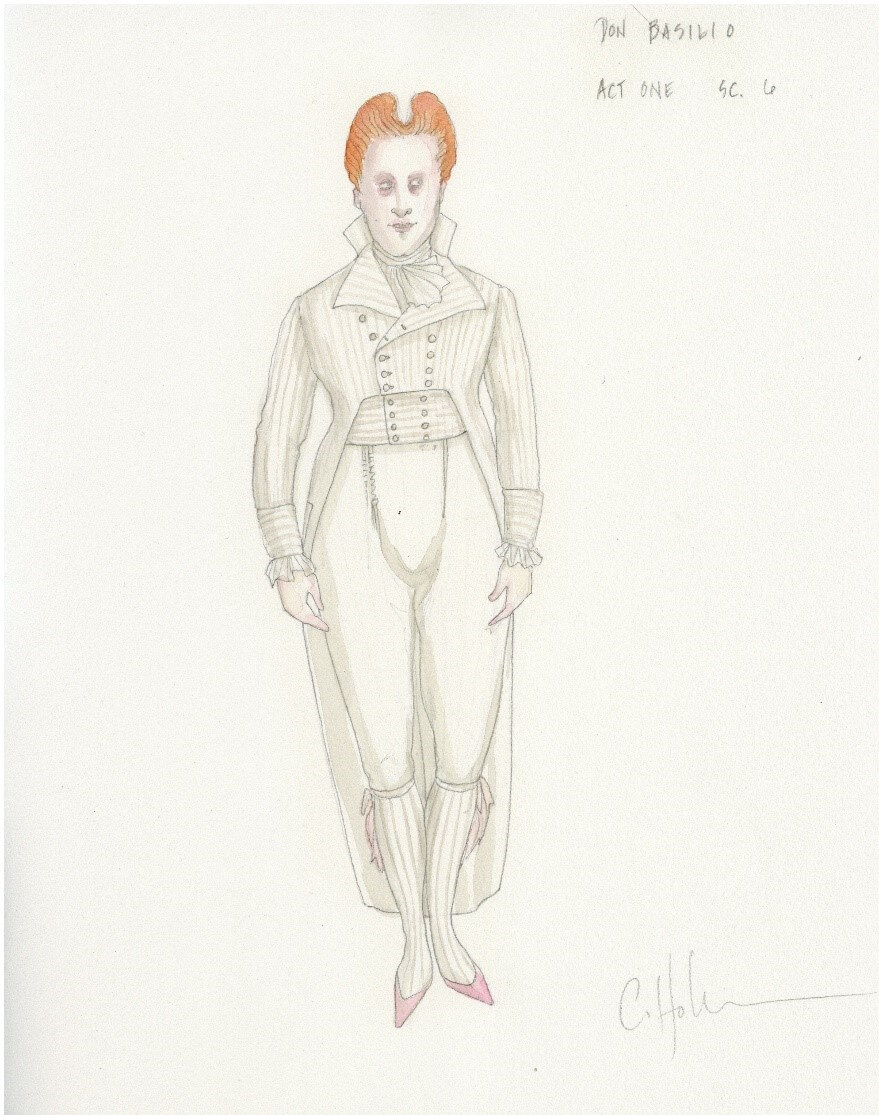

It’s so easy to fall in love with Constance’s costume designs. Even on paper, they leap out from the page with beauty, character and depth. Each one is an artwork in and of itself, and tells you so much about the motivations of the character being clothed. As you work with Constance and see her dedication to research, to fabrics, to techniques, to craft, you get so excited for how these designs will translate into costumes.

We’re going to take a look here at how the early part of that process is going for The Marriage of Figaro, as the San Francisco Opera Costume Shop begins the process of building our new costumes. Chorus costumes will be built and fit first; principal costumes come much later so they can be finalized once the cast arrives for rehearsals.

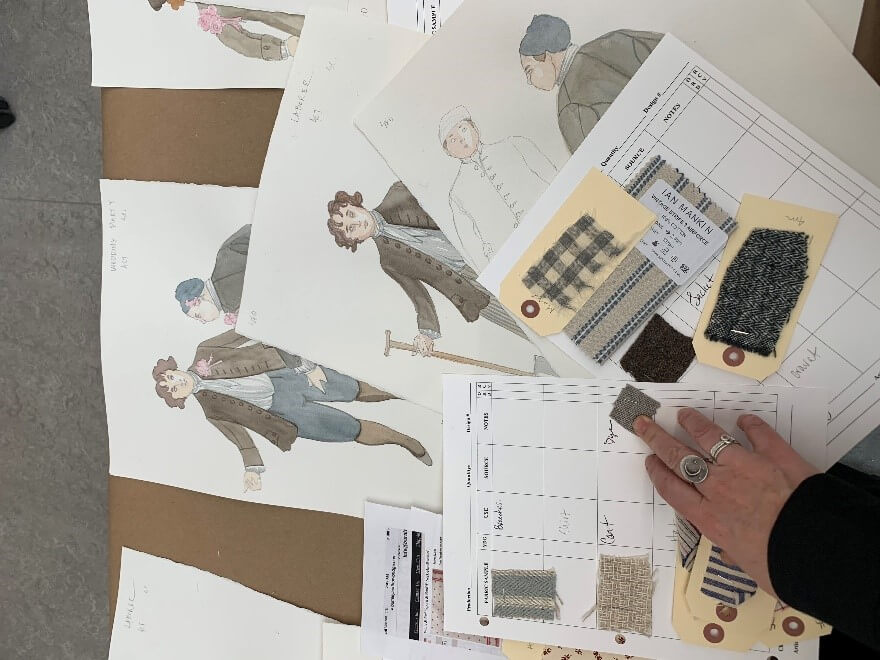

At this point, with the designs completed, the focus is on fabric selection. Constance is working intensively with our Costume Shop to put together the fabrics that will allow each design to be translated into clothes, ensuring that fabrics can be sourced, purchased and worked with, all in time for our October opening. When Constance was here for our official design presentation in November, she did some preliminary work with the Costume Shop supervisors, Jai Alltizer and Galen Till. This allowed Jai to do some sourcing while in London in December to see our new production of Hansel and Gretel. At the same time, Constance and her assistant in New York did some “swatching” there, resulting in an unusually abundant selection from which to choose.

The process of collecting fabric swatches (“swatching”) varies depending on how much of a fabric industry a city still has. In New York and London it is still a very hands-on process—as Constance notes “this work is done on foot with a pair of scissors, a stapler and a ring full of oak tag cards.” Each fabric swatch is carefully recorded to identify the shop name, the price and the width of the fabric. In other markets it is done through catalogues and requesting samples by mail.

Constance has huge respect for the SFO Costume team and their ability to source fabrics from the universe of suppliers and options. In addition to swatching in New York and London, we have huge binders of swatches here in the Costume Shop, and those become invaluable additions.

For this production, although it is set in early America, getting fabrics from London was particularly important given the traditions and designs that have survived in London from that era. Hopkins Fabrics is a trade-only organization that still has period looms from the 18th-century, and are able to dye-vat fabrics in a way that gives a period feel. Cloth House in London is another great resource: they specialize in Indian block prints which were very common in 18th century clothing (think Jane Austen period films).

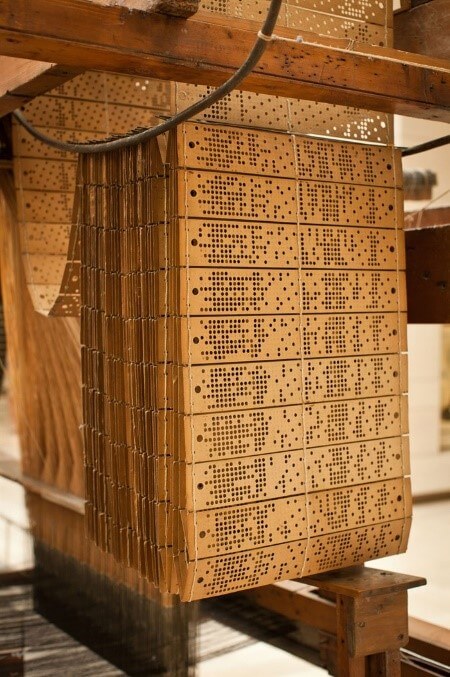

Constance told me how much harder it is to find great fabric stores in recent decades. I was fascinated to learn that much of the specialty stock of fabric stores comes from left-over cloth created for fashion houses. Now that digital looms are so accurate and cloth can be more easily custom woven for the fashion houses, there is less waste, leaving much less stock for fabric stores!

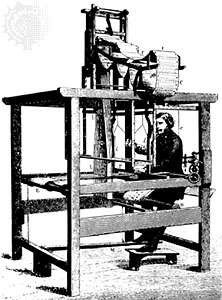

The idea of a digital loom has a strong precedent. Looms were perhaps the very first examples of computers with the Jacquard loom of 1801 using a punch-card system to automate the weaving process and allow for the replication of more complex designs.

Now, Maison Henry Bertrand in London has taken the computerization of weaving to a new level with an incredible ability to customize both colors and patterns. This allows for very fine variations in shade and shape, giving a costume designer like Constance previously unimaginable flexibility.

As Constance notes, she can now truly ‘paint’ with woven fabrics, so subtle are the nuances. She really does consider fabric selections like painting—she thinks about how to distribute color, texture and impact onstage across the whole range of characters.

With a panoply of fabric swatches at their disposal, Constance and the costume supervisors begin work on creating the ‘Costume Bible’—the master plan of all the details that will go into each costume. Each page of the costume book represents an individual costume and is divided up into each element of that costume from underskirts to shawls to hairpieces. As Constance selects fabric for a costume, a small piece of the swatch is cut out and attached to the page, along with notes about any fabric treatment, e.g. whether it needs to be dyed, embroidered, distressed, etc. From here, the supervisors will work to determine how much of each fabric to order, note the source, confirm availability, etc. They catalogue it all so that it can be sourced and built both now and then long into the future if new versions are needed (e.g. for new casts).

Almost all of the sourcing and selections for The Marriage of Figaro have been completed, but the scurrilous character of Basilio is still not quite there. He has an all-white suit and white fabrics are notoriously hard to work with in theater to ensure that the costume is readable from the house. But he’ll be taken care of ‘ere too long!

I asked Constance if she ever changes course in a design as she begins to work with the fabric. She says only very rarely. She regards the designs as a contract between herself, the director and the producer (SF Opera), and that, once approved, the designs should remain firm. If a substantive change does emerge, it’s a case of going back to the director and discussing whether that is a viable new perspective.

Working on a production process like this, where each of the costumes is an individual piece (unlike e.g. Turandot where the chorus are all wearing similar costumes), it is particularly important to have a system that allows you to work quickly and efficiently. Constance has developed a technique over time to set up the swatches in advance so that they are easily comparable—all the jacket fabrics, apron fabrics, wedding dress fabrics, etc., attached to cards, ordered, catalogued and easily accessible. The first day of this process is to create all the swatch cards that will form the basis of the fabric selection. This allows Constance to feel much more connected to the fabrics, and to mix and match them and compare them against each other.

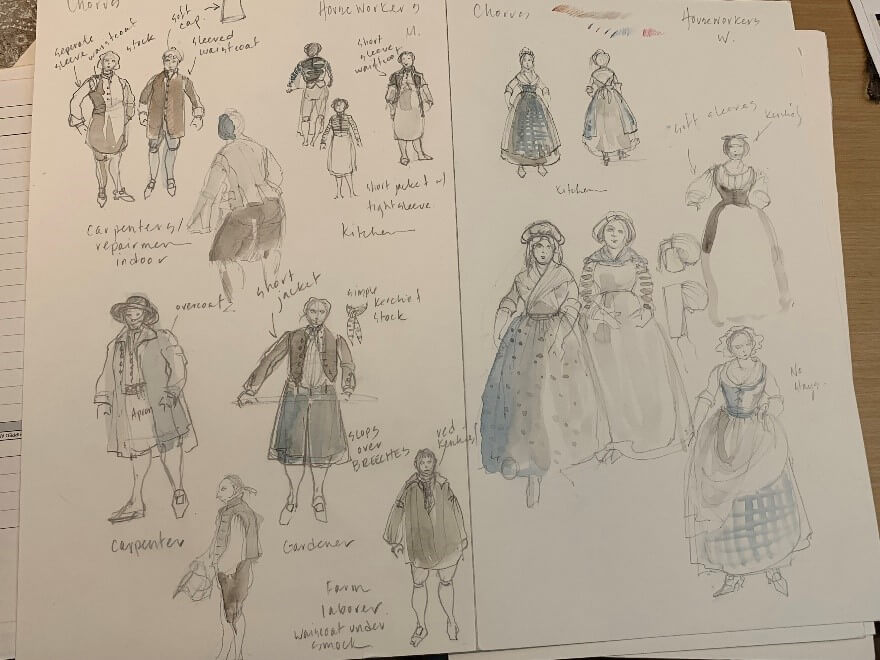

I noticed on the Costume Shop tables that Constance had several early sketches out—little thumbnails of the characters, heavily annotated. She told me that she often returns to these early sketches because they help her reconnect to the energy of her early ideas—to see the spread of characters on one page, and to feel the vitality of that early part of the creative process. As you can see in these chorus characters below, one of the early focusing points of the color palette was for the chorus to have an almost dusty quality to them. The house is still under final construction in The Marriage of Figaro and the chorus almost blend into the dust of the building process. Keeping these thumbnails on hand allows Constance to stay very true to the process.

As fabrics are compared and selected, the Costume Shop uses lighting instruments to see how fabrics will look and feel under theatrical lights. It’s critical that the ultimate end-use of a theatrical stage is always kept in mind.

The process so far has moved from conception to design to fabric selection and the creation of the costume bible. As fabrics are now purchased and shipped to San Francisco, the Costume Shop will begin the building process in preparation for Chorus fittings later this spring. We’ll revisit the process as it unfolds, but it is fascinating to see the incredible skill and artistry that goes into bringing Constance’s designs into a tactile world of fabrics and textures, and to realize how a blend of cutting-edge technology and age-old fabric techniques combine into what will be an exquisite set of costumes ahead.

The wardrobes of our Great American House are in the very best of hands.