Backstage with Matthew: An Epic Jigsaw Puzzle

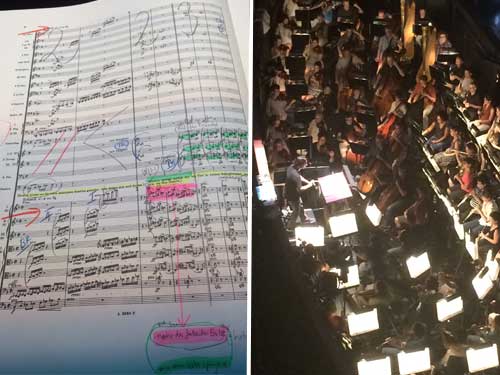

Elektra claims an important superlative. It uses the biggest orchestra of our repertory with 95 instrumentalists crammed into the pit to create an awe-inspiring musical texture. Under the insightful baton of Hungarian Maestro Henrik Nánási, the impact of so many players is one of the great auditory experiences you will have in this house. Messiaen’s St. François in 2002 did spill out of the pit, with platforms built to create a second level. However, that was for logistical reasons—the size of the percussion and keyboard sections required more physical space than we had. However, the number of people was still smaller than Elektra. The forces in Elektra are staggering. Usually you have first and second violin sections. In Elektra you have third violins, adding a whole new section! Most operas use 2-3 clarinets. Elektra uses 8! Most operas use 4 horns. Elektra—8, of which 4 double as Wagner tubas. Wagner and Strauss operas generally call for an extreme orchestra. Elektra pushes it that little bit further.

This begs the fundamental question: how do you fit everyone in?

Most Opera Houses struggle to get 95 people into the pit. In San Francisco, our pit is long and narrow, making for some particular challenges. Even a regular Verdi or Puccini opera with 65-or-so players can feel crammed. Adding another 30 is a near-impossible task, but under the experienced guidance of our Orchestra Manager, Tracy Davis, we find a way!

Tracy has been with San Francisco Opera since 1993 when he joined as Orchestra Manager after a stint with the Sacramento Symphony as both Players’ Manager and percussionist (he studied at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music and the Eastman School of Music). As the Sacramento Symphony fell into bankruptcy, the Orchestra Manager job was being advertised at San Francisco Opera.

In this role Tracy is responsible for ensuring that the orchestra is fully staffed at each rehearsal and performance irrespective of illness, injury, or emergency. He has a massive address book of all the accomplished instrumentalists in the Bay Area and, using a substitute list approved by the Music Director and the section principals, he is responsible for filling any absences. This requires knowing the specific talents that each musician brings to bear: who is a proficient sight-reader (playing with no rehearsal), who will blend well with the other members of the section, and who is available, sometimes on just a few hours’ notice. Tracy tells me he once sat in a Safeway parking lot on the phone, calling 20 horn players to try and fill an emergency vacancy! Tracy is also responsible for all of the orchestra payroll, the oversight of instruments owned by the Opera (mainly percussion and unusual instruments like Wagner tubas and basset horns), overseeing the orchestra auditions, and all of the personnel management. Tracy still plays percussion with the Orchestra from time to time! It’s a huge job and, since 2010, Tracy does it not only for the Opera Orchestra, but also the Ballet Orchestra!

But, back to squeezing 95 musicians into the War Memorial pit…

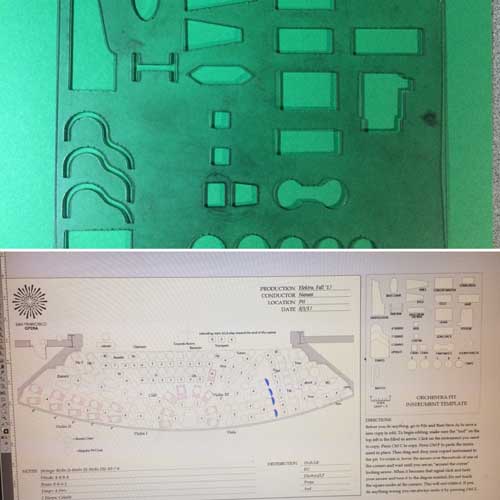

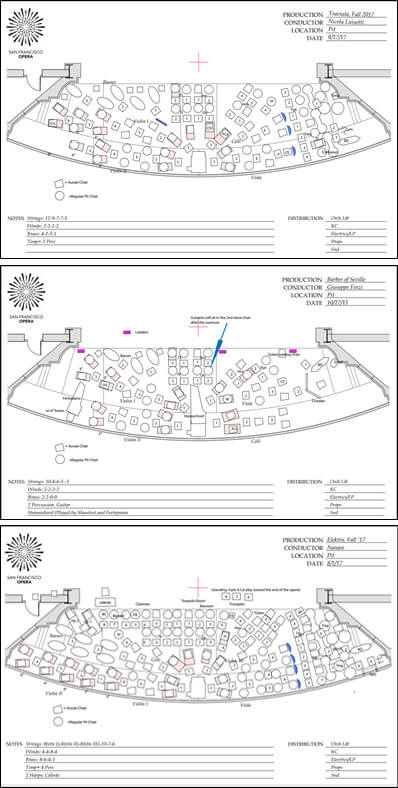

The basic guide for this is the “pit plot.” This is a diagram of the pit into which Tracy fits each instrument. He strives to give each player as much room as possible, within the framework that each conductor is hoping to achieve. There is no set placement of instruments in an opera orchestra. Strings in particular move around quite regularly, depending on the preference of a particular maestro. Although the winds tend to sit on the back wall of our pit, and the brass and percussion off to the right hand side, there are no absolutes. And then you have the operas with keyboards—pianos, harpsichords, organs, etc. that need to be squeezed in.

When Tracy started, he would use a stencil created by the technical department that included the footprint of the main instruments in the orchestra. He would literally draw the pit plots by hand using the stencil to find the best fit. In more recent years, he has moved to Adobe Illustrator and an electronic version of the stencil. Now he can move around instruments, music stands and sound shields (designed to mitigate sound impact in the pit) with great ease. He says that most pit plots go through 2-3 revisions during the course of a rehearsal as we work to find the optimal configuration. But he remembers one production where there were 8 versions! Taking into account the particular preferences of a given maestro, Tracy will often do an initial proposal, then refine it with the maestro.

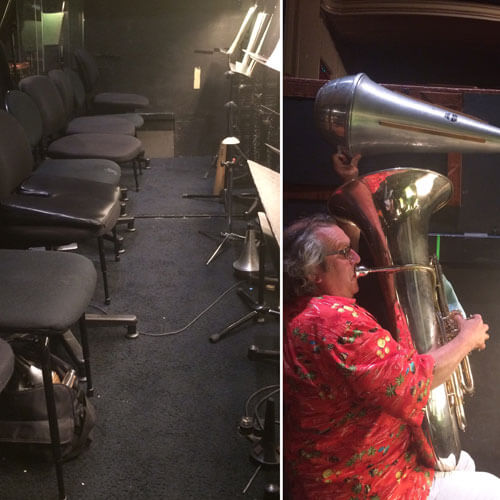

The images below show three different pit plots. One is for Traviata which represents a relatively ‘normal’ orchestra configuration and size in the pit. Then there is Barber of Seville from a few years ago, which is a much lighter orchestra, and includes two keyboards for recitatives. And then there is the mighty Elektra orchestra pit plot. No spare room at all! In fact, the Elektra needs are so great that we have to use something called the ‘torpedo room’ which is a narrow corridor just behind the pit that accesses the prompt box. Three of the trumpets and the celesta keyboard have to make home there.

Elektra is one of the most challenging orchestral scores in the repertoire and requires huge stamina. It is 105 continuous minutes of intense symphonic music. Add onto that the cramped living quarters of the Elektra pit and you get a sense of both the musical and logistical demands that the members of our Orchestra are working through in this piece. There’s just about room to play your instrument. Beyond that, there’s no room to move. That makes it a little tricky when you need to do something like lifting a tuba mute in an out: you have to resort to balletic moves with your instrument!

As I write this we’ve just finished an orchestra staging rehearsal of Elektra and the quality of music making is staggering: a testament to the extraordinary talent that we have in our renowned orchestra. That they are able to do all of this in such tight proximity is thanks to the amazing expertise of Tracy Davis, the man who keeps the Orchestra working smoothly and, hopefully, with a little elbow room.

Here’s to a spectacular opening of the 2017–18 Season! I cannot wait to share it with you.