‘Live for Your Craft:’ Tenor Michael Fabiano Shares Wisdom From His New Documentary

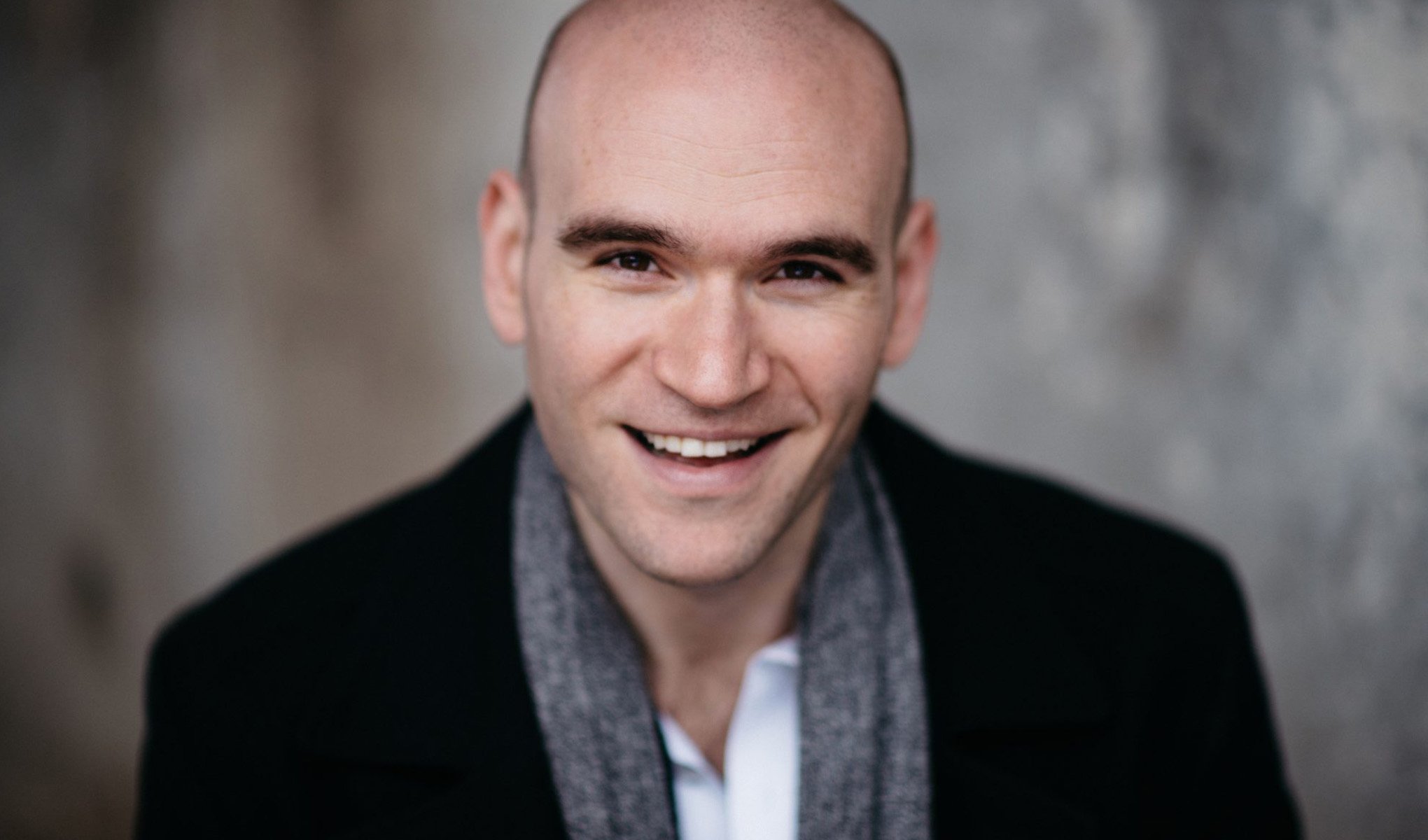

Nominated for the Critics Choice Documentary Awards and presented at the 2020 Tribeca Film Festival, Crescendo! tells the story of how the New Jersey-born Fabiano started singing at an early age—only to encounter bullying as a child both for his singing and for his sexual orientation.

“I had the shit beat out of me a number of times,” he tells the camera with disarming frankness. “When I came home with a pencil shoved in my arm and blood everywhere and I was too scared to go to the nurse because I thought I’d get beat up the next day even more, that’s bad.”

But Crescendo! reveals that, even as an adult, Fabiano faced pressure to hide who he was, for fear being gay might alienate prospective audiences.

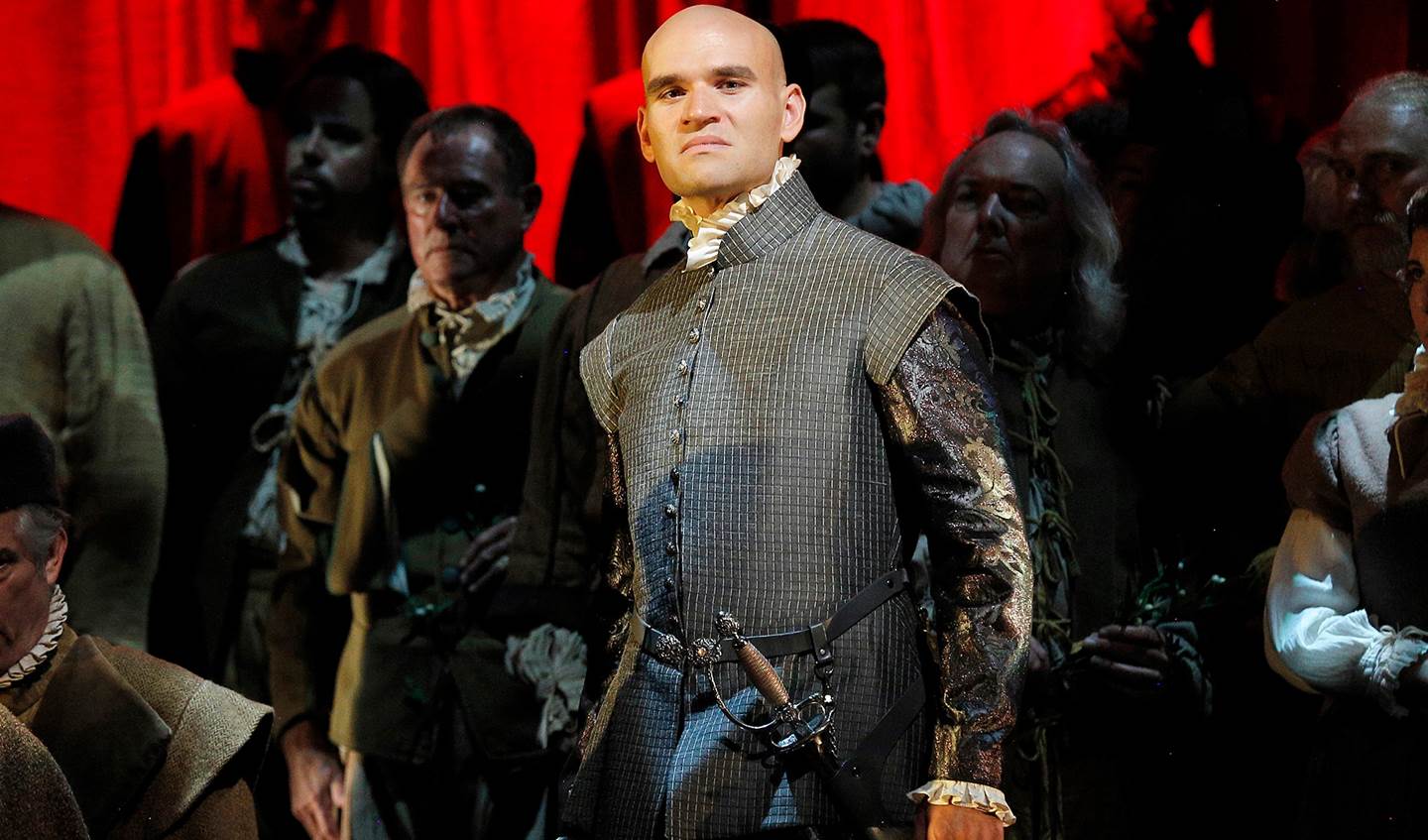

Fabiano was an opera star on the rise: He was the first person to win both the Richard Tucker Award and the Beverly Sills Artist Award in the same year. It was his job to bring to life dashing rogues and winsome lovers. Industry insiders warned that being openly gay would damage his prospects for getting cast.

“I think there are perception issues,” Fabiano explains in a recent interview with San Francisco Opera. He faced questions like, “Can a gay man play a romantic lead in Italian and French operas that are quintessentially known for being the romantic partners of women on stage?”

Those questions initially left him with doubts. While he was open with his family and friends, as a young artist he remained apprehensive about identifying as a gay man in public, lest it detract from his ability to play heterosexual roles on stage.

“I’m a masculine man. I'm just gay. But I think there's an unconscious thread, even in the eyes of the public to a degree, where it would be harder for people to conceive of that to be so,” he says.

But at the height of Crescendo!, Fabiano reflects on coming out publicly as gay—and finding acceptance within the opera industry all the same. The film carries as its subtitle: “On how NOT to remain quiet with Michael Fabiano.”

Mentored by some of the great tenors of the 20th century, including George Shirley and Neil Shicoff, Fabiano projects unflappable strength, a steadfast confidence that belies the hurdles he has overcome. For him, the art is paramount. He aspires to disappear into a role, to incarnate it fully.

“As artists, we are chameleons,” he explains, paraphrasing his friend, soprano Latonia Moore. “Every opera I sing, I have to engender and embody a new person.”

And yet, as a tenor at the top of his craft, he is equally a public figure, followed around by film crews and journalists, not to mention tens of thousands of fans on social media. He was only 22 years old when he was featured in the feature-length documentary The Audition, broadcast on PBS stations across the country.

Speaking by phone on a train from New York, Fabiano shares a glimpse at the “private Michael” that no camera can capture—and explains why he chose to brave the spotlight yet again in Crescendo! For Fabiano, it’s in service of an important message: that forced conformity “is when tyranny sets in.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: Who approached you about the documentary [Crescendo!]? Was it the director?

FABIANO: No. It started for multiple reasons. One? Perri Peltz is a woman I know, who was one of the two executive producers, she and Matthew O’Neill. We were having a conversation with my aunt Laurie, who is the president of the Tory Burch Foundation, basically an organization that works at empowering women leaders around the world.

People were making observations about the openness of the arts and culture. And I just said very casually—I swear, this is how it started, very casually—how one might perceive the arts to be very gay and LGBT in front of the curtain. But the perception is not the reality.

Ears popped up and people said, “What do you mean? The arts are of course gay.” And I said, “Yes, I would say on the whole that's true.” The community is extremely open-minded and accepting. And among the people that I know that work behind the curtain in particular, there’s a large amount of gay men and women.

So we ended up having this conversation. And she said, “Well, certainly there must be lots of gay stars out there.” And I said, “I can't point to many in opera. That’s the reality.”

When we filmed this and began these discussions, this was five years ago. So that's a small caveat to add: I think, even in the last three years, there has been progress that we didn't see beforehand. Five years ago, I couldn't point to an internationally acclaimed tenor that was similar to me. Certainly there are some, of course, gay tenors in our business, gay men, but not at the level that I sing. And that asks a lot of questions, I think.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: You mentioned that you'd noticed a shift in the past few years. How have you seen that shift?

FABIANO: I would say a line my aunt Laurie uses a lot. Laurie is one of my heroes and inspirations. She's an incredible woman, Laurie Fabiano. She often talks about unconscious bias. And we find that that issue comes up, I would say, with talking about race more than it does even about sexuality and gender. What kind of bias do we have when we look at people? What does it feel like?

And I think the fact that people are more conscious of each other and their ability to exist equally in society is why it's become easier for people that are gay. Because what has been unconscious is now conscious.

Now that doesn't negate necessarily law or issues that are happening on a local or a statewide level. I'm not arguing that. But I'd say—on an interpersonal level, on a person-to-person basis—there is a clear difference. I can feel it myself. And I would argue that a lot of gay men and women would say the same.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: In opera, when I think of the things that we think of as openness in opera, for example, pants roles are often brought up. [“Pants role” is a term in opera typically used to describe women playing men on stage.] But as liberating as it can be for women to wear masculine clothing and express desire for another woman on stage, oftentimes these are served as scenes of laughter, scenes of comedy. And ultimately they go to serve a heterosexual plot. Do you ever feel hemmed in by the classical repertoire?

FABIANO: No is the answer. And my position would be, if people feel hemmed in, then they shouldn't sing classical works. They should sing modern works that address those issues because these works are what they are. They're historical. They were written from a heteronormative, largely white society. We know that.

So if there's a problem with it, then people shouldn't sing it. They should do things that serve their interests and make them feel validated. They shouldn't feel hemmed in by that notion. Again, I'm sure that's contrary to what you'd expect a person like me to say, but I really believe that.

Forcing the business to change something that existed 150 years ago—that is still beautiful and still has life—is not going to make the art better. What's going to make the art better is promoting new works. It's having those artists that might feel constrained by that stuff do new things—be a part of new projects that highlight the stories that people haven't told.

I’m fully in favor of the crafting of new incredible works. And by the way, I would love to be a part of them. If I was asked to be a part of a musical drama that had to do with gender and sexuality, I would jump at it because there are not enough of those stories being told.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: One thing that you spoke about in the documentary is that you perceive opera audiences being conservative in some ways.

FABIANO: Yes.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: I wonder, could you explain what you meant by that?

FABIANO: First, as a young person, I was told many times that, if I were to tell people my sexuality, a lot of the older clientele that populate operas would be less inclined to buy tickets to watch me. Because I am, in fact, gay.

Even people that would be—quote—liberal by today’s standards suggested this to me, which was: “Don’t talk about your sexuality if you want to have a career, because the audience can skew conservative. The audience prefers heteronormative relationships on stage. And it's going to be harder for them to conceive of it if there's a gay man kissing a woman.”

I heard that for a long time. And then I finally just said, “I have no problem kissing a woman, even if I'm gay. And if I do it and people have a problem with it, they can go screw themselves. I don't care.”

That's literally what I thought. I will embody these characters because I believe in the character and I believe in the work. And if they don't like me, they don't like me.

People have a right to reject me. I can't be scared of rejection. I get rejected all the time. I've been booed hundreds of times on stage. I've gotten reviews that you can’t imagine have been written. So I just decided that, if I get rejected by some people, screw it. I don’t care. It doesn't matter. Other people's opinions of me do not define me.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: When you're talking about these negative reviews that you receive or being booed, a lot of people would have been deeply hurt by that and may have even considered leaving the art form. Has that ever been a possibility that's crossed your mind?

FABIANO: No. And the answer is a definitive “no” on that for multiple reasons. I'm lucky. For one, I've had mentors in my life that have taught me from an early age that I live for my work. I don't live for other people. I serve my muse. I don't serve the whims of journalists or the whims of other musicians.

And I really hope that, as I grow older, I'll be able to compel lots of young people on this exact same topic, which is: Don’t live for applause. Don't live for the approval of others. Don't live for the approval of famous musicians. Work hard and work for your craft. Live for your craft. And if you do that, I have to tell you: It is so freeing. It is so freeing. The work is a total joy, even if people don't always like it.

So that's the first thing. I’d say there have been moments in my career where I thought maybe I should do something else, but not because of negative opinions. Because of the hustle and the bustle of the career and how aggressive it can be. It's weird, admittedly, that I'm never in a fixed city more than two months a year. That's hard. And I do want to have kids and a family someday. I really want that.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: It strikes me that you've had to grow up a lot on stage—

FABIANO: Oh yeah.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA:—and to grow up through documentary even, with The Audition and up to present day.

FABIANO: Sure, totally.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: Can you talk to me about what that's like? What that's like: being followed around with a camera and having to—in a sense—play yourself for the general public, even when you are off stage and out of character?

FABIANO: There’s so much to peel away here for you. It's a very emotional topic for me too, I have to say. The first caveat and overview is that often, even with the camera, we don't always see the truth.

People don't see when we are alone. People don't see what it's like to be away from my dog for a year and a half. People don't see what it's like to not sleep in my own bed. People can't feel what it feels like to not be able to hug my mother for two years. That's never able to be consumed in, quote, an up-close visual.

The harsh reality about what we do is that the life of an artist who is an opera singer in particular is a life of solitude. It is a life of hard work. It is a life of deep commitment and focus. And a camera can’t pick that up.

What can a camera do to show deep commitment, focus, and loneliness? How does the camera show that? It doesn’t. And no one ever asks this question, which is why I'm really touched that you asked it because I think it's the question that no one wants to be answered, which is: What truly is behind the curtain?

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: What did you hope to communicate with this latest documentary?

FABIANO: That everybody should not fear, should never fear, having their own voice. That's very important to me right now. I think that we're in a world where there is a lot of social shaming and social pressure to conform on all fronts, left and right both. And I reject that entirely.

It's my sovereign right to have my own beliefs. It's my sovereign right to sing how I want to sing. And if people want to judge me, they can judge me all they want. But at the end of the day, I'm the one out there doing it. And I think the message to younger people is: Go for it. Jump out there. Don't wait in line. Be your own person. Have your own ideas. Don't be forced to conform.