In Memoriam 2021

Karan Armstrong, soprano

Karan Armstrong, a leading soprano for nearly four decades with Deutsche Oper Berlin, began her musical journey as an American pianist. Born in Havre, Montana, Armstrong took up singing in college and continued her vocal studies with conductor Fritz Zweig and soprano Lotte Lehmann. She was selected for the Merola Opera Program in 1965 and made her stage debut as Musetta in a Merola production of La Bohème. The following year she won first place at the Metropolitan Opera’s 1966 National Council Finals, securing a cash prize and contract to sing at the Met. After performing smaller roles at the Met, Armstrong took on leading roles at New York City Opera and was contracted to sing overseas. In Stuttgart and Berlin, she often collaborated with director Götz Friedrich whom she eventually married. Her acclaimed, otherworldly portrayal of Elsa in Friedrich’s production of Lohengrin at the 1979 Bayreuth Festival precipitated a later recording and telecast. As her European commitments increased, Armstrong’s appearances in the United States became less frequent. But in 1986, she returned to San Francisco, the city where her stage career had begun two decades earlier. Sharing the bill with Menotti’s The Medium starring Régine Crespin, Armstrong’s mainstage debut in Poulenc’s one-woman show, La Voix Humaine, would not be overshadowed. The Sacramento Bee praised her “acting tour de force” and observed that “her soprano is of complementary quality, gorgeous and velvety in its middle registers and spine-tingling up high.” (JM)

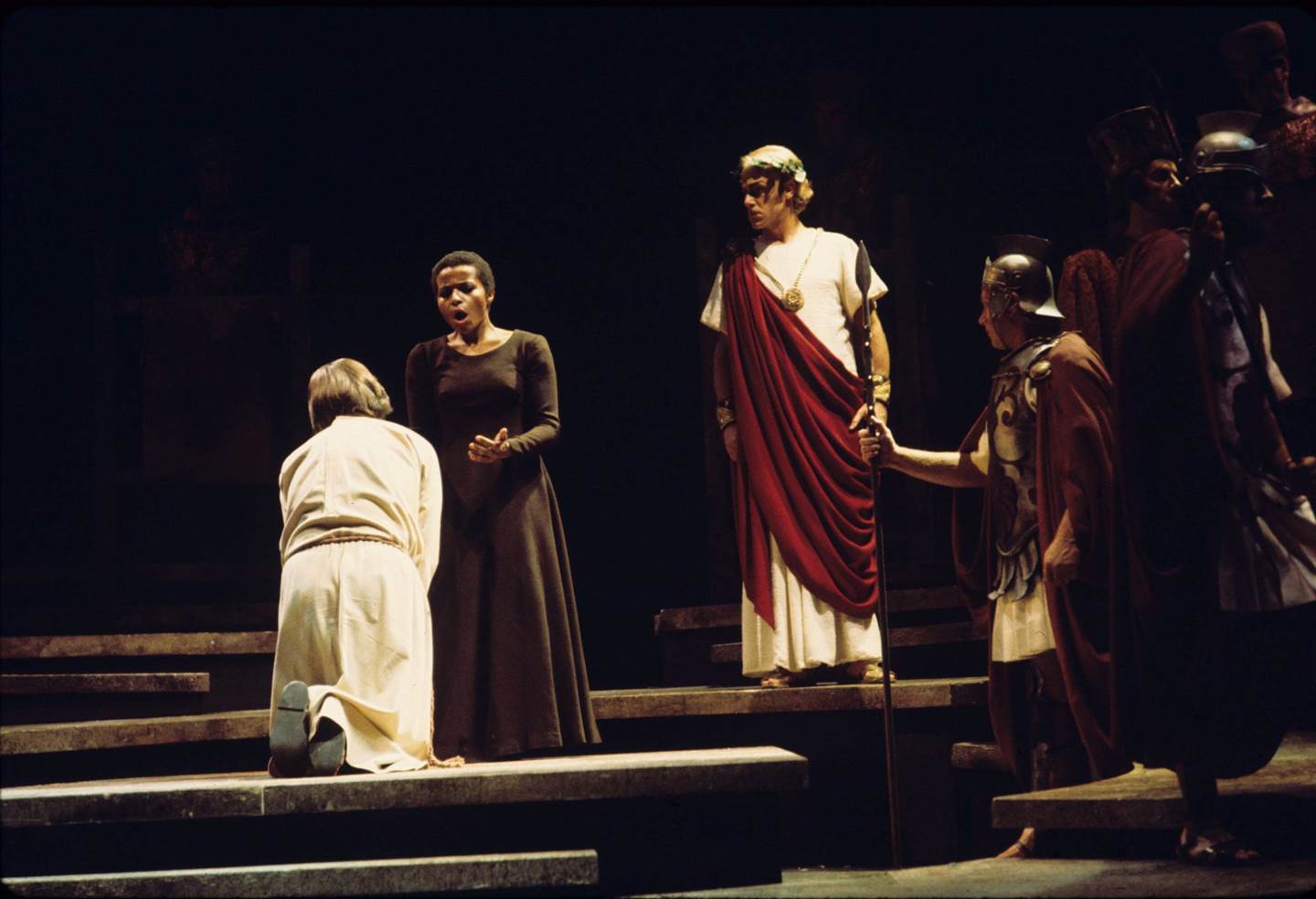

Carmen Balthrop, soprano

The luminous voice of Maryland native Carmen Balthrop was first heard in San Francisco in 1973 when she sang the soprano solos in Spring Opera Theater’s staged production of Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion. She reprised the role in the 1976 revival. She returned in 1979 as Ruggero in Rossini’s Tancredi opposite Marylyn Horne in the title role and in 1986 performed Bess here in Houston Grand Opera’s touring production of Porgy and Bess. In 1975, besides winning the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions, she captivated national attention with her interpretation of the title role in Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha at Houston Grand Opera (later produced on Broadway and also televised in a 1978 Houston revival). Her performance awakened the world not only to the depths of her artistry but also to the greatness of the neglected opera. She made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1977 as Pamina in The Magic Flute and was soon launched onto the international stage. Later in her career she shared her interpretive gifts as a teacher of voice at the University of Maryland. (KC)

Nancy Bechtle, philanthropist

As at home at the opera and symphony as she was at bluegrass concerts, Nancy Bechtle had a demonstrable knack for connecting the arts and her community. Earlier this year, the philanthropist and ardent arts advocate opened the door for San Francisco Opera to bring mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton and banjo virtuoso Béla Fleck together for one of the Company’s In Song episodes. San Francisco Opera General Director Matthew Shilvock said, “If there was great music happening in the city the odds were that Nancy was a part of it, sometimes even taking part in it!” Along with her philanthropic work, Bechtle was a noted musician who fronted her own band, Nancy and the Lambchops, and made her mark with her original song “Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff!”

Born Nancy Hellman in New York City, she grew up in San Francisco while also spending lots of time on the family ranch in Vacaville, reportedly operating a tractor before she learned to drive a car. Her first musical love was opera, encouraged through attending on a Tuesday subscription with her grandmother. Before long, her passion led her into service and leadership with several arts organizations, beginning with the San Francisco Conservatory of Music in 1973. She was a member of the San Francisco Opera Board of Directors from 1982–2002 and remained deeply committed to the Opera, attending opening night of the drive-in Barber of Seville last spring with husband, Joachim. Bechtle provided leadership to many organizations and causes, including a 14-year term as president of the San Francisco Symphony from 1987–2001, and long-time service on the War Memorial Board of Trustees, the National Parks Foundation, the Presidio Trust, UCSF, the Sugar Bowl Corporation and the Charles Schwab Corporation.

Shilvock said, “It was a privilege to know Nancy, to be inspired by her passion and positive energy, and to see the extraordinary impact that she made on the cultural life of the City in so many ways. Nancy was a radiant light in our world.” (JM)

Carlisle Floyd, composer

“Something of a milestone,” is how Arthur Bloomfield described Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah when it was given by San Francisco Opera during the Spring Season of 1964. “A pithy opera, rushing firmly to its conclusion with music easy on the ears but integral to the drama, it could hardly help making a rather strong impression, and it attracted about 4,000 customers, divided over two performances.” When David Gockley became general director of San Francisco Opera in 2006 he already had a strong working relationship with Carlisle Floyd, honed by their work together at Houston Grand Opera where Gockley had commissioned several new works from the composer as well as staging his older operas like Susannah. So it was with special pride that Gockley brought Susannah back to San Francisco Opera in 2014.

Susannah, written in 1955, was Floyd’s third opera and his greatest success. It received the New York Music Critics’ Circle Award and was America’s official entry at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels. It is one of the most performed of all American operas. The world of Susannah—a small rural community set in the Appalachian hills, deeply suspicious of anyone who appears to deviate from its strict religious mores—was one composer/librettist Floyd knew well. He was born in 1926 in South Carolina. His father was a circuit riding Methodist minister and Floyd grew up attending revival meetings and seeing the power a charismatic preacher could wield over an audience.

Floyd created over a dozen operas, writing the libretto as well as the music. Of Mice and Men, an adaptation of the John Steinbeck novel, was originally commissioned by San Francisco Opera, but ended up premiering at Seattle Opera in 1970. San Francisco Opera affiliate Spring Opera Theater gave it at the Curran Theater in 1974.

Floyd once told an interviewer what he looks for in choosing a subject: “An abundance of emotion, rich characters and very dramatic situations or incidents. There are a lot of things you can do in a play that I don’t think are appropriate for opera at all. Anything that has to do with philosophical, intellectual disputes you just can’t use on the opera stage. Anything that’s highly internalized or requires a great deal of verbiage unaccompanied by action is best avoided.” He also talked about the potential disagreement between Carlisle Floyd the librettist and Carlisle Floyd the composer. “As a librettist, the composer part of you is always breathing down your neck. You’re always asking, is this too talky, is the action carrying the story line? You can’t impose a musical structure on a libretto—or vice versa—without serious consequences. But the composer always wins. He’s a real tyrant.”

In 2004 Floyd was awarded the National Medal for the Arts. The Citation began: “For giving American opera its national voice in a series of contemporary classics rooted in American themes.” And it quoted Andrew Porter’s words in The New Yorker: “He has learned the international language of successful opera in order to speak it in his own accents and to enrich it with the musical and vernacular idioms of his own country.” (PT)

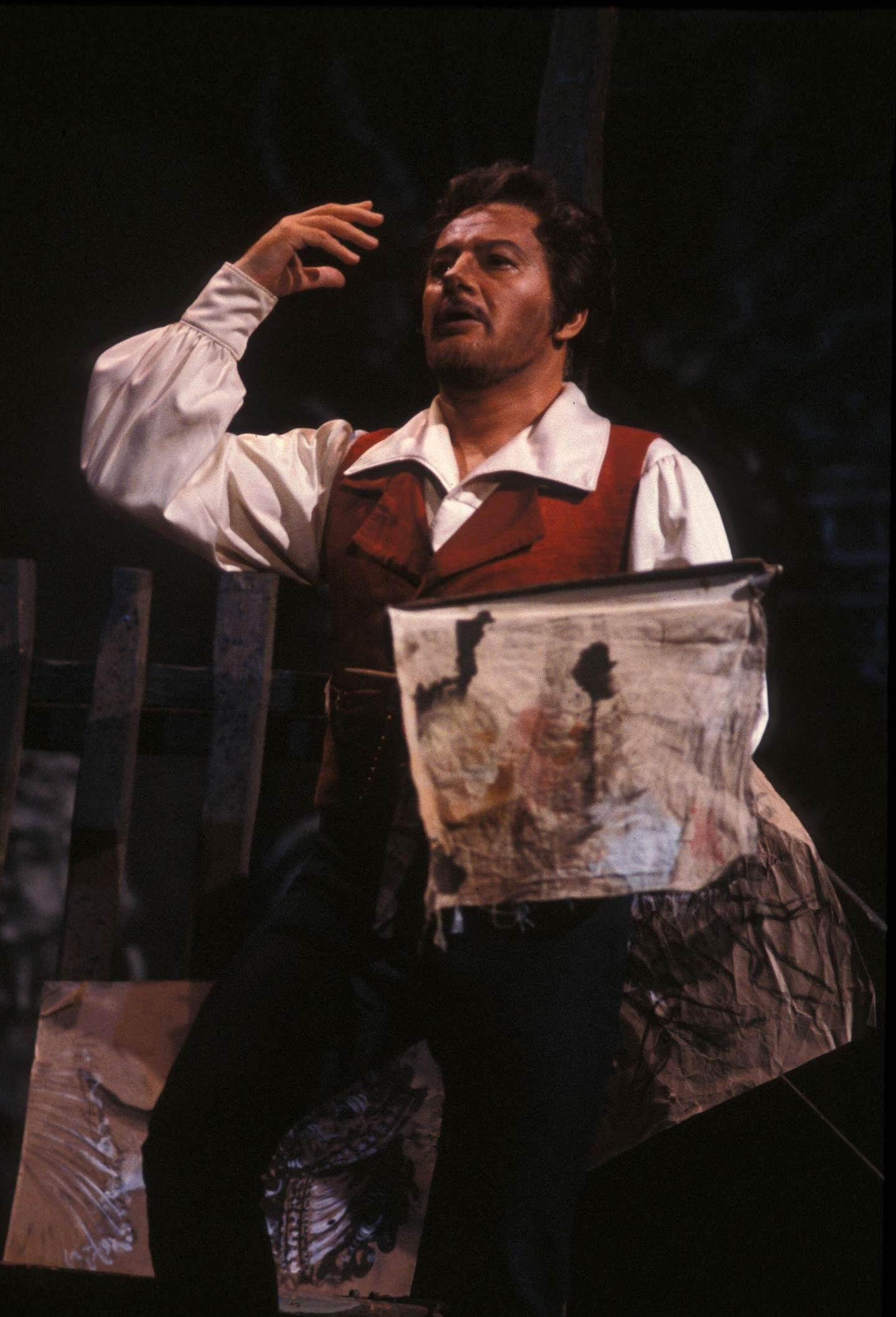

Giuseppe Giacomini, tenor

In December 1979, San Francisco Opera traveled outside the United States for the first time when it presented three performances of Puccini’s Tosca and a concert in Manila, sponsored by the Opera Guild of the Philippines. Tenor Giuseppe Giacomini made his Company debut singing Cavaradossi in the final Tosca. In 1985 he repeated the role—this time in the War Memorial Opera House. When he sang his first Cavaradossi at the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Times reviewer commented, “In some respects Giuseppe Giacomini gave the most winning performance of the evening. [He] sang Cavaradossi with honest, heart-on-sleeve emotion … On the whole his instrument is a ringing, robust, firmly centered tenor of first-rate quality.”

In an interview he gave toward the end of his long career Giacomini said, “The beautiful sound for me is the one that is loaded with great emotions. I’ve always been looking for this: this sound that takes all my soul, that—no matter whether I’m saying the word ‘Amore’ or I’m shouting—has plenty of my intimacy. That’s the beautiful sound. Surely it must be sung with the discipline of the technique, always, but this is the beautiful sound in my opinion because it’s rich with emotions, it’s rich with my soul.” (PT)

Clifford Grant, bass

As a young man, Sydney-born bass Clifford Grant performed all around Australia with different opera troupes. In 1965, opera’s power-couple of soprano Joan Sutherland and conductor Richard Bonynge discovered his talent and doors began opening for the bass. An audition for Sadler’s Wells in London led to his debut as de Silva in Verdi’s Ernani and a continued presence with the English National Opera forerunner. During his decade with the company, Grant appeared opposite mezzo-soprano Janet Baker and assumed multiple roles in conductor Reginald Goodall’s English-language production of Wagner’s Ring. Concurrent with his years in London, Grant became a fixture with San Francisco Opera. He made his American debut on the War Memorial Opera House stage in 1966 as Lord Walton in Bellini’s I Puritani in a cast headed by Sutherland as Elvira and with Bonynge on the podium. During the Company’s 50th anniversary season in 1972, Grant performed Hunding and Hagen in the new Ring production and, again with Sutherland and Bonynge, as Oroveso in a new staging of Bellini’s Norma. Oroveso would be one of Grant’s most memorable portrayals with the Company, appearing opposite the Normas of Sutherland, Rita Hunter, Christina Deutekom, and Shirley Verrett, the latter for his final San Francisco engagement in 1978.

Following his tenures at Sadler’s Wells and San Francisco Opera, Grant spent many years with the Australian Opera, finally retiring from the opera stage in 1990. Grant’s wife, Ruth Anders Grant, recalled, “Cliff was a stage manager’s nightmare—noisy, full of laughter, and sometimes chatting so loudly in his dressing room that he would miss his call and run on to the stage in a panic, flinging his chewing gum at the back of the scenery. He would painstakingly collect it on the way back.” (JM)

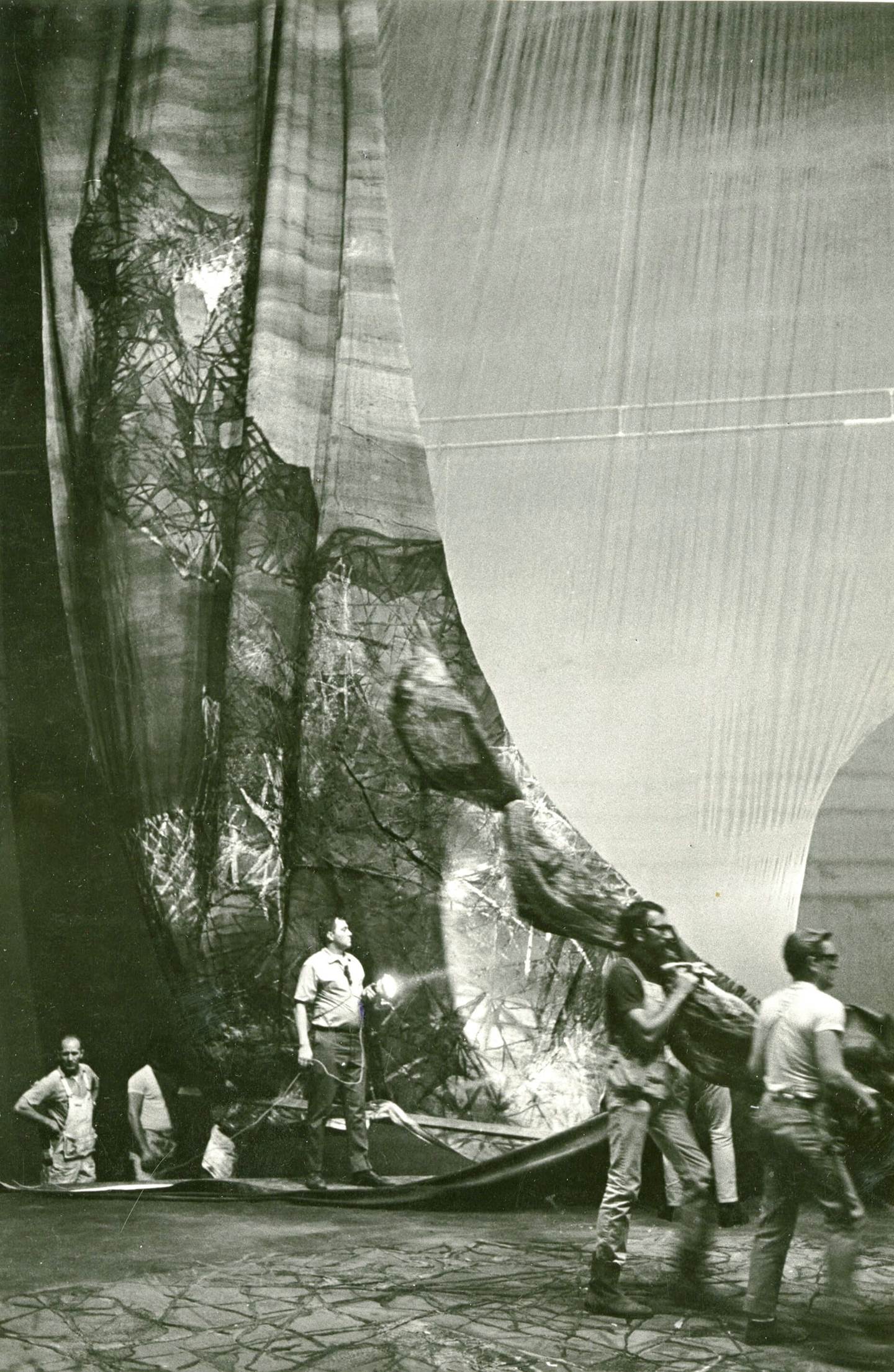

Michael Kane, master carpenter

In 1966, at just 31 years of age, Michael Kane became the youngest master carpenter to ever serve at the War Memorial Opera House. The Kansas City-born Kane had arrived in San Francisco via Spokane, Washington where he spent his early years working for the Northern Pacific Railroad and in the Army National Guard. To earn extra income, he found part-time work as a stagehand at the Spokane Coliseum, a move that would illuminate the path to a lifelong career in the theater. At age 25 he married Peggy Lafferty and the couple moved to San Francisco in 1960. Kane joined the International Alliance of Theatrical Stagehand Employees Union (IATSE), Local 16, and went to work in the Opera House for both San Francisco Opera and San Francisco Ballet. Promoted to master carpenter after just six years, Kane would serve in that role for 28 years and oversee the building of many complex opera productions, including the world premiere of Andrew Imbrie’s Angle of Repose (1976), a new Ring cycle (1972), and many other new productions and revivals. When he retired in 1994, Kane was awarded the Opera Medal, San Francisco Opera’s highest honor, and SF Ballet awarded him the Lew Christiansen Medal for his many years of service as master carpenter and production manager. A memorial service for Kane was held in October at the location that was central to his life’s work, the stage of the War Memorial Opera House. (JM)

James Levine, conductor

In 1970, a year before his first performance at the Metropolitan Opera, the 27-year-old James Levine made his San Francisco Opera debut conducting Tosca, starring Dorothy Kirsten and Plácido Domingo. When he returned the following year for Madama Butterfly, San Francisco Examiner critic Arthur Bloomfield noted, “James Levine was back on the podium, offering the same grand, surging style and penetrating dramatic sense experienced in his Tosca the previous year.” By 1973 Maestro Levine was named principal conductor at the Met, and became music director in 1976, a post he would hold for four decades, conducting more than 2,500 performances. He vastly expanded the Met’s repertory and honed the orchestra into a much-admired, world-class ensemble. His “Live From The Met” broadcasts made him internationally recognized.

A child prodigy as a pianist, the Cincinnati native performed Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with the Cincinnati Symphony at age 10. He served as music director of the Munich Philharmonic for five years (1999–2004) and had long associations with the Boston Symphony, the Berlin Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic, and the Chicago Symphony’s Ravinia Festival. His numerous recordings and videos displayed a prodigious talent, but his career ended in scandal after serious accusations of misconduct toward young men and boys. (KC)

Christa Ludwig, mezzo-soprano

San Francisco Opera General Director Kurt Herbert Adler had been courting the German mezzo (and occasionally soprano) Christa Ludwig for years before she finally appeared at the War Memorial Opera House in 1971 as Octavian in Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier. It was one of her most famous roles but in her autobiography, she refers to Octavian as a “still-wet-behind-the-ears playboy.” She further reveals, “He understands absolutely nothing about the wise things the Marschallin says to him, which, I suppose, is the privilege of youth. And I never liked singing him either. He has a few beautiful phrases, but nothing really easy because he’s suddenly always hitting high notes without any preparation. I also didn’t care to play him because I always had to be careful about how much I ate.”

Still, in his history of the Company Arthur Bloomfield applauds her “superbly aristocratic Octavian” and the fact she “sang with a tastefully creamy, unforced tone.” That was the way Ludwig sang everything from Bach to Berg to Bernstein, whether she was appearing in opera, in recital, or in concert with an orchestra. In addition to her considerable vocal and acting gifts, she also had that indefinable “something” that makes an audience genuinely love a performer, to feel a personal connection with them. During her time in San Francisco that connection resulted in Ludwig having an unexpected (and unsettling for her) evening with some fans that could have come right from Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City. A fan called and invited her to dinner and since Ludwig was alone, she accepted. But rather than going to a restaurant as she had thought, she found herself at the house of the “very good-looking young man” who had all her recordings. Inside she was greeted by a group of young men “who seemed to be living in a kind of commune.” In the middle of a living room was a big black waterbed they insisted she try. “They started to smoke, but I declined with thanks—it smelled a bit sweet in the room already.” Everyone was a huge opera fan, the vegetarian food “was very tasty … they served a good California wine, and everything was very charming.” Though as quickly as she could, Ludwig excused herself, worried that no one knew where she was.

Ludwig’s San Francisco Marschallin was Sena Jurinac and according to Bloomfield, Adler thought it might be a great idea for the two ladies to switch roles in the last Rosenkavalier. By 1971 Ludwig had begun singing the Marschallin, and Octavian had been one of Jurinac’s parts earlier in her career. Adler did not insist, and it remained only an interesting idea. Unfortunately, illness forced Ludwig to cancel her planned return to San Francisco Opera, to open the 1973 season in Donizetti’s La Favorita, leaving her Bay Area fans only with the memory of her Octavian. (PT)

Jan McArt, mezzo-soprano

Jan McArt made her Company debut in 1955 as the Milliner in Der Rosenkavalier tending to another debutante, German soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, who was appearing in staged opera in the United States for the first time as the Marschallin. Throughout McArt’s three seasons with San Francisco Opera, the young American mezzo-soprano performed a handful of supporting roles opposite several operatic legends like Schwarzkopf. McArt was a Page in Lohengrin while titanic-voiced soprano Inge Borkh portrayed Elsa; she performed several small roles in Charpentier’s Louise while Company prima donna Dorothy Kirsten sang the title role; she was Giannetta in L’Elisir d’Amore which featured Patrice Munsel, Giuseppe Campora, and Italian master Italo Tajo as Dr. Dulcamara; and she appeared alongside Turkish soprano Leyla Gencer in her American debut in Zandonai’s Francesca da Rimini. A dependable San Francisco Opera artist during Kurt Herbert Adler’s first three seasons as general director, McArt soon refocused her energies toward musical theater and Broadway. Trips to visit her ailing mother in Palm Beach County during the 1970s led to starting several theater companies in Florida. By the time she retired to Boca Raton, McArt was affectionately known as Florida’s first lady of musical theater. (JM)

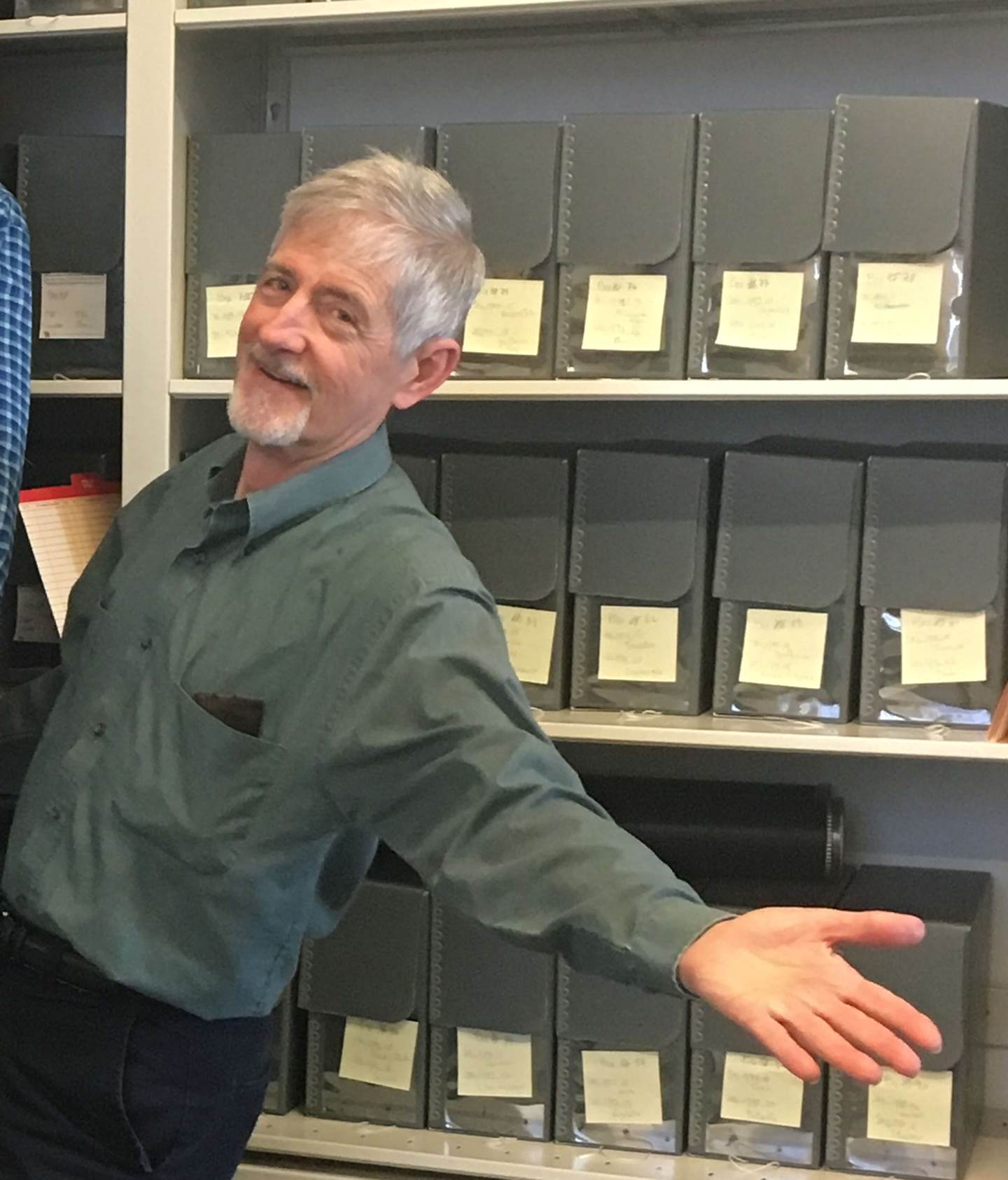

James Nance, San Francisco Opera Archives volunteer

Armed with a background in music education as well as instrumental and vocal performance, Jim Nance began his 8-year stint as a volunteer in the Company’s Archives with a solid grounding in the world of opera. His dedication and deep knowledge of the Company’s administrative history contributed materially to the Archive’s operations and resources, especially his culminating legacy work: a multi-year project to gather, in one location, the names of all those who have played a role in making this Company what it is today. Scouring records from 1923 up to the present, Nance methodically gathered the names of every administrator and board member; all chorus, dance, and orchestra members; and the supernumeraries and cover/understudies, too. As we prepare to celebrate our Centennial season, Nance’s work will take on an even larger role in helping to make informed connections between the past and the present. His generous and playful spirit will be fondly remembered. (BR)

Evgeny Nesterenko, bass

Born in Moscow in 1938, Evgeny (or Yevgeny) Nesterenko joined the Bolshoi Opera in 1971 and led a decorous stage career there encompassing some 50 leading roles, including the acme for any Russian bass, the Czar in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Unlike many of his colleagues in the former Soviet Union, Nesterenko also established himself as a solo artist internationally, performing frequently at London’s Royal Opera, the Vienna State Opera, and Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. In 1979, he bowed with San Francisco Opera as King Philip II in Verdi’s Don Carlo in a cast including Giacomo Aragall in the title role and Anna Tomowa-Sintow as Elisabeth. It would be his only appearance with the Company. The Los Angeles Times said he “sings the tragic utterances of King Philip II with rolling ease, reasonable amplitude, wide ranging equality of tone and timbre, and the sort of granitic low notes for which Russian basses have been celebrated since the golden days of Chaliapin.” Nesterenko amassed an impressive discography, documenting numerous Russian works in all-Russian productions along with contributions to celebrated recordings like the Faust with Kiri Te Kanawa and Francisco Araiza and Carlo Maria Giulini’s classic recording of Il Trovatore with Plácido Domingo as Manrico. (JM)

Vladimir Redkin, baritone

Born in Moscow and trained at the city’s conservatory, Vladimir Redkin joined the Bolshoi Opera as a young man and remained with the company throughout his long career. Like Nesterenko (see above), Redkin was one of few Bolshoi standouts to enjoy a flourishing international career during the peak of the Cold War. He performed at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala, the Vienna State Opera, and with companies in Scotland, Ireland, Spain, France, Germany, Israel, Chile, and the United States. His first American performances occurred in 1991 when the Bolshoi Opera visited New York and Redkin was heard in the title role of Eugene Onegin. His only season with San Francisco Opera came in 1993 when he appeared as Prince Yeletsky in Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades with fellow Russian artists soprano Maria Guleghina and elder Bolshoi legend, tenor Vladimir Atlantov. (JM)

Gianna Rolandi, soprano

Opera News magazine described Gianna Rolandi as “one of the brightest stars in the impressive cadre of American-born and American-trained singers who achieved professional success in the 1970s.” The coloratura soprano was born in New York City but raised in South Carolina. Despite an international career, she always considered New York City Opera to be her home. It was there she was mentored by Beverly Sills, “my biggest cheerleader and fiercest critic.” She inherited many of Sills’ most famous roles including the title role of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, the role of Rolandi’s San Francisco Opera debut in the summer season of 1986, and one she sang in a Live From Lincoln Center telecast. The New York Times described her first City Opera Lucia as “riveting” and went on to say “her singing and acting had both shown splendid finesse.” When Rolandi returned to San Francisco in September 1986 in Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, opposite Samuel Ramey and Kiri Te Kanawa, the San Francisco Chronicle found her Susannah to be “fresh and original.” Her last appearances with the Company were in 1988, as Despina in Mozart’s Così fan tutte, a part she once described as “my role.” Rolandi was married to British conductor Andrew Davis. They met when he was conducting Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos at the Metropolitan Opera and she was singing Zerbinetta. “We didn’t particularly hit it off particularly well,” she later admitted. “I didn’t like his tempi and I don’t think he liked me at all.” But a couple years later they met again at the Glyndebourne Festival in England and married the following year. (PT)

William Rusconi, violin

San Francisco Opera’s 1971 Season, the Company’s 49th, opened with a new production of Massenet’s Manon starring Beverly Sills and Nicolai Gedda. Few outside the orchestra pit likely noticed that the auspicious evening also occasioned the debut of a young second violinist with the San Francisco Opera Orchestra. William Rusconi would retire from the ensemble 36 years later, a beloved Company mainstay whose career coincided with numerous milestones in San Francisco Opera history. He performed during the Company’s 50th and 75th anniversary seasons, for three general directors and two music directors, and was in the Orchestra for countless debuts and new production premieres, including the unveiling of two new stagings of Wagner’s Ring Cycle in 1972 and 1985.

Jack Schaeffer, photo gallery consultant

Since the opening of the Diane B. Wilsey Center for Opera in 2016, concert goers, tourists, community members, and Company staff have marveled at its twin galleries of archival San Francisco Opera photographs. Jack Schaeffer, along with his ACT3 Partners business partner, Jeff Hurn, were the creative team who helped San Francisco Opera turn an aspiration into a stunning reality for this permanent exhibition chronicling the Company’s rich history and bold, creative trajectory heading into the future. While Hurn worked magic on decades-old negatives and prints, Schaeffer was the visionary guiding Company staff in the selection, production, and installation of the images. At the ribbon cutting for the exhibition, the San Francisco Chronicle commented: “The 135 images here, drawn from the archives of the San Francisco Opera, cover the nearly 100 years of the company’s history with a sweep and vitality that are wonderful to behold. The display has been arranged with an eye to both elegant patterning and serendipitous interconnection.” An infectiously joyous collaborator, Schaffer had a passion for working with San Francisco Opera on the galleries. His enduring legacy is available to all who stroll down the corridors on the fourth floor of the Veterans Building, finding inspiration in 100 years of vibrant theatrical history. (BR)

Charlotte Mailliard Shultz, philanthropist

For over half a century, Charlotte Mailliard Shultz was the city of San Francisco’s chief of protocol, overseeing events and diplomatic functions within the city. It was an unpaid position, but an essential one. In her time in the role Shultz played host to business leaders and artists, activists and politicians, counting many world leaders among her guests, including Pope John Paul II and Queen Elizabeth II. Just as she fostered relations between San Francisco and the world, she also built strong ties between the city’s cultural organizations and the community. Shultz served on nonprofit boards across the city, including San Francisco Opera, and was a longtime trustee for the War Memorial Opera House. Born to parents who ran a Texas five-and-dime store, Shultz told the San Francisco Chronicle she fell in love with San Francisco after taking a peek inside Grace Cathedral. “Unless I’m thrown out of this town,” she thought, “I’m not leaving.”

Later in life, she married former Secretary of State George Shultz, who passed away earlier this year in February. The couple never missed San Francisco Opera’s free Opera at the Park concert in Golden Gate Park and were frequent guests for events and performances at the Opera House. The horseshoe drive at the War Memorial is named in their honor.

San Francisco Opera General Director Matthew Shilvock said: “I think that Charlotte should have had the title of Impresario of the City. Her ability to mobilize anything and anyone into action was unlike anything I have ever witnessed, particularly in a City where hurdles are plentiful. Charlotte would call with an idea but it was never to discuss whether it might work. There was never a question of that; only how quickly we could make it happen. But that was absolutely fine because they were always excellent ideas. Within a day or so of the Notre Dame fire in April 2019, Charlotte called me to see if we would participate in a concert at Grace Cathedral to show solidarity to our sister city in Paris. About a year later, Charlotte phoned again: she would like San Francisco to come together in song to raise the spirits of the City as the magnitude of the pandemic became apparent, and she wanted our Chorus to participate. Within five days she took the sing-along from an idea to a city-wide reality, including her dear friend Tony Bennett in the proceedings. And these are just two recent examples. Time and time again, Charlotte envisioned how the City needed to come together and, with a few compelling phone calls, it was all set into motion. Red tape meant nothing to Charlotte. She just took a large pair of scissors to it!”

Andrew Sinclair, director

Australian stage director Andrew Sinclair was an active figure at major international theaters, including the Royal Opera House, New York City Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Seattle Opera, Washington National Opera, among many others. His engagements at San Francisco Opera included productions of Bellini’s Norma (1998) and Bizet’s The Pearl Fishers (2005). From 1983 to 1985, he was principal resident director of Opera Australia in Sydney, where the telecast of his production of La Bohème garnered an Emmy Award in 1989. Sinclair became a staff director for the Royal Opera in 1994 and worked with the company until 2019. At his passing, the Sydney Morning Herald commented, “ Opera informed his life, enlivened his spirit, and aroused his curiosity and creativity. Andrew’s knowledge of opera was vast and unquenchable, and, for more than 40 years, he brought these qualities to bear on a huge array of productions directed or restaged by him across the world.” Speaking of his working relationships, his fellow Australian conductor Simone Young remarked, “Whether you were the youngest props assistant at a college or the most famous diva on the grandest stages, Andrew valued your work and contribution to the great art form that he lived for.“ (KC)

Michel Trempont, baritone

Belgian baritone Michel Trempont was an established singer in Liėge and Brussels in the mid-1950s, long before international opportunities beckoned him to appear abroad. In 1966, Trempont appeared at the Opéra-Comique in Paris as Figaro in a French version of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro and was appearing soon thereafter on the leading stages of Aix, London, Milan, and Venice. He made his American debut in 1981 with San Francisco Opera as Géneral Boum in Offenbach’s Le Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein with soprano Régine Crespin in the title role. Trempont’s talent for creating unforgettable characters on stage found expression in his subsequent appearances for the Company: Beckmesser in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg under the baton of former general director Kurt Herbert Adler, Sancho Panza to Samuel Ramey’s Don Quichotte in Massenet’s opera, and as Sergent Sulpice in Donizetti’s La Fille du Régiment with Kathleen Battle’s Marie. His final appearances with the Company were in the dual role of Benoit and Alcindoro in La Bohėme, the latter opposite the feisty Musetta of Anna Netrebko. Reviewing his Sancho Panza for the Los Angeles Times, Martin Bernheimer said Trempont’s performance was “dramatically earthy and musically elegant. He steadfastly avoided comic caricature and, despite rather slender baritonal resources, tugged the assembled heart-strings heftily in the climactic scena.” (JM)

Graham Vick, director

British director Graham Vick, noted for his emotionally incisive and imaginatively revisionist productions, gave San Francisco Opera his distinctive interpretations of Tannhäuser in 2007 and Lucia di Lammermoor in 2008.

His concentration on psychologically probing drama led him to avoid lavish spectacle, often staging operas in unconventional venues such as airplane hangars, factories, warehouses, and nightclubs, with a strong determination to bring opera to the people and widen its social appeal.

He declared in remarks to the Royal Philharmonic Society in 2016, “You do not need to be educated to be touched, to be moved and excited by opera. You only need to experience it directly at first hand, with nothing getting in the way.”

Vick’s first major appointment was as director of productions for Scottish Opera (1984–87), winning fans and foes for his provocative production style.

He was later director of productions at the Glyndebourne Festival (1994–2000.) At the time of his death from complications of COVID-19, he was artistic director of the Birmingham Opera, which he founded in 1987. Earlier this year he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II. (KC)

Gerhard Woelke, volunteer

San Francisco Opera artists, staff, and patrons will miss the kindness and ever-thoughtfulness of Gerhard Woelke, longtime War Memorial Opera House volunteer usher. Woelke was especially beloved backstage where he diligently assisted with coffee service for artists and staff before and during performances. Born in Danzig, Germany, in 1939, his family moved to Hamburg during the War. Gerhard eventually struck out on his own and moved to Los Angeles to take a job as a ticket agent for Lufthansa. When he was transferred to Lufthansa’s San Francisco office as a sales representative, he found the city that would be his home henceforth though Woelke remained an avid traveler. He also loved celebrations and traditions, including walking across the Golden Gate Bridge every January 1.

San Francisco Opera would like to honor all six of the volunteer ushers who passed in 2021: Carl Folk, Edward Gutman, Georgia Lee, Hellen Manougian, George Weiss, and Gerard Woelke. (JM)

Teresa Zylis-Gara

Polish soprano Teresa Zylis-Gara made her American operatic debut in San Francisco in November 1968 singing “a luxuriously creamy and resilient” Donna Elvira in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. It is no surprise she once described Elvira as her “destiny role.” Before her US performances she had sung it at her Salzburg Festival debut with Herbert von Karajan conducting. The Los Angeles Times’ critic, Martin Bernheimer, wrote of her San Francisco performances that Zylis-Gara, “sang a Donna Elvira that easily withstood comparison with the finest recent exponents of that difficult role, Sena Jurinac and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf.” When she repeated the role for her Met debut a month later, critic Irving Kolodin wrote, “Her voice is both bright and substantial, which means that she can convey the intensity of emotion in the role—she is, after all, the only one who truly loves the Don—without sounding shrewish. The last great Elvira, in a quite different way, was Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Zylis-Gara, an accomplished technician as well as a good-looking woman and capable actress, could well take over both the role and the rank of her distinguished predecessor.”

Zylis-Gara decided at the age of 16 to devote herself to opera and in 1954 won first prize in the Polish Young Vocalist Contest. She made her professional debut two years later at the Krakow Opera. In the early 1960s she settled in Germany to pursue her career which quickly took her to all the top opera houses. She sang a wide repertoire, from Monteverdi to Krzysztof Penderecki. Not surprisingly she had a special affinity for Tchaikovsky’s operas in which she could be especially moving, and her final performances with San Francisco Opera in November 1982 were as Lisa in The Queen of Spades. (PT)