‘The International Language Is Music:’ Opera Star Justino Díaz Reflects on a Life in Song

It was September 16, 1966. The Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center was about to open for the first time. And the red carpet outside the theater was packed with dignitaries arriving to inaugurate the occasion with a new opera: the world premiere of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra.

There were ambassadors from some of America’s most prominent families: Rockefellers, Fords, and Kennedys. There were vice chancellors from West Germany and architects from Palm Beach. And then there was Lady Bird Johnson, the president’s wife, side by side in her fur stole with Philippine autocrat Ferdinand Marcos and his pearl-studded spouse Imelda.

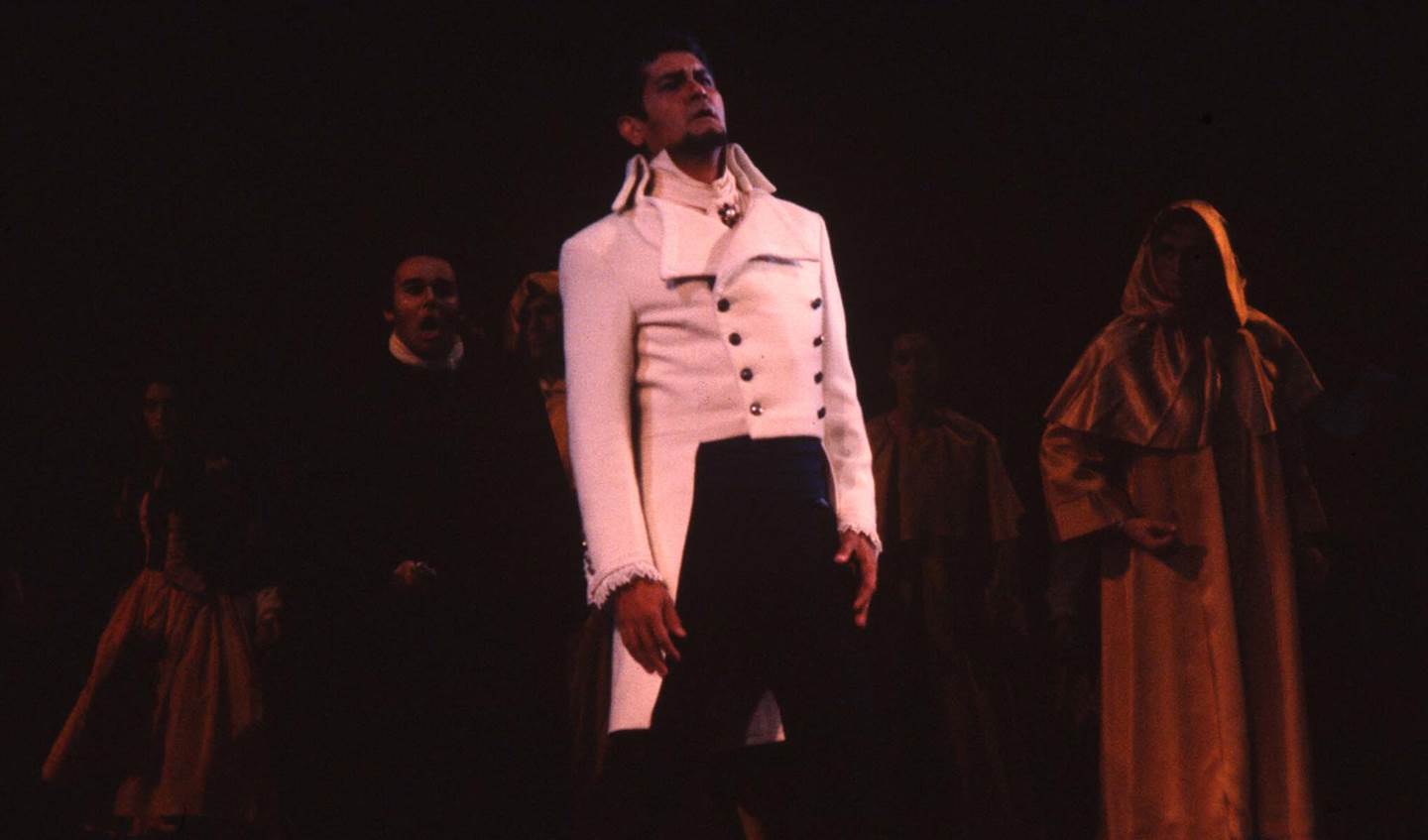

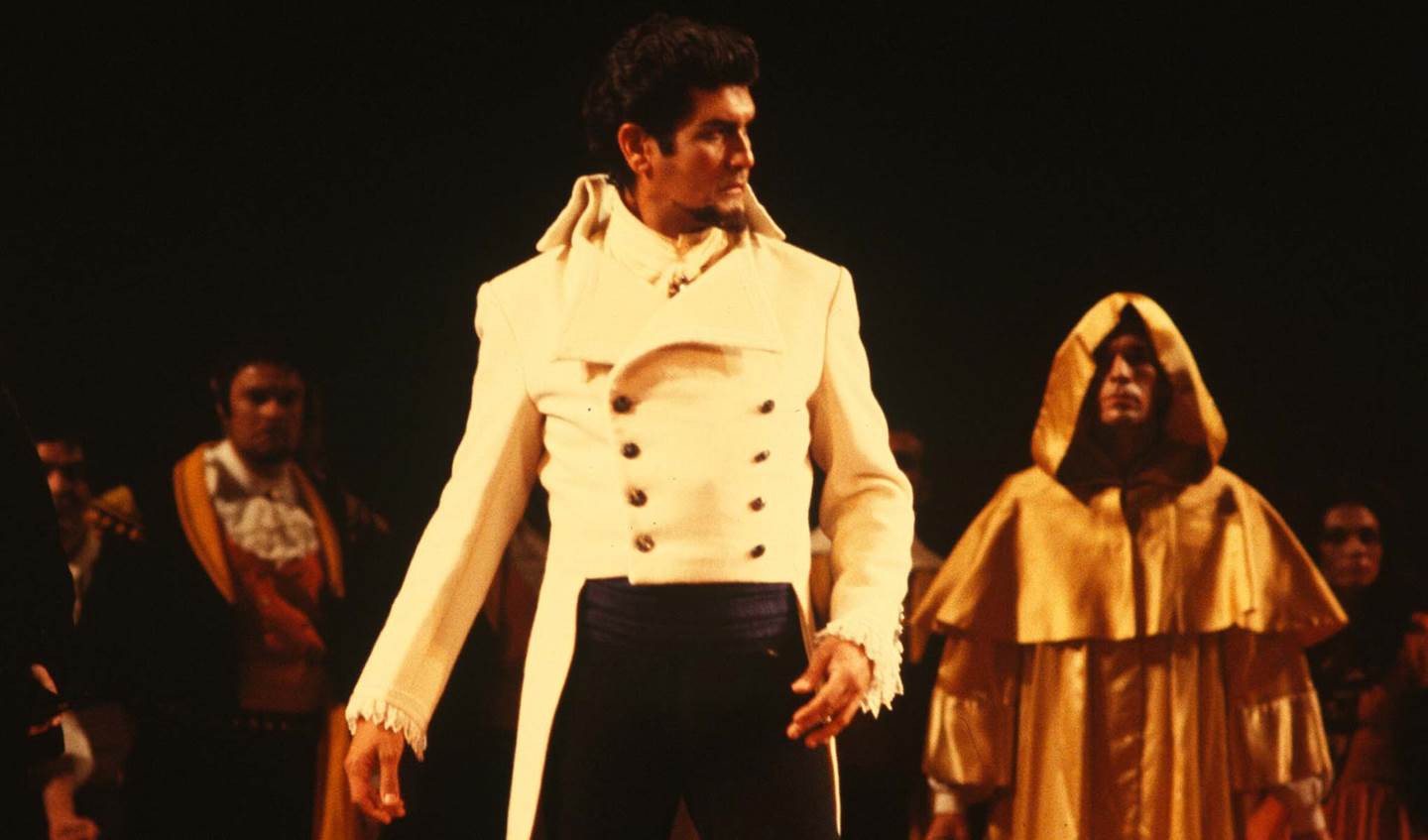

For the next two hours, all of their eyes would be locked on the same stage, where a 26-year-old bass-baritone was about to take the spotlight: Puerto Rican performer Justino Díaz.

Young, with a mighty voice and a mane of dark hair, Díaz was soaring on the crest of a meteoric career. At the tender age of 23, he had won the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions, the most prestigious young artist competition in the industry.

His victory earned him a contract with the Metropolitan Opera. And that contract catapulted him from opportunity to opportunity, in operas like Rigoletto, Samson and Delilah, and Faust.

Ultimately, his powerful, rumbling voice landed him the role of a lifetime: the lead in Antony and Cleopatra, opposite legendary soprano Leontyne Price as the Egyptian queen.

Starring in Antony and Cleopatra may have been Díaz’s first time opening a major American opera house—but it wouldn’t be his last. Five years later, in 1971, he would help inaugurate the Kennedy Center Opera House too, with the world premiere of composer Alberto Ginastera’s Beatrix Cenci.

This Sunday, December 5, he returns to the Kennedy Center—not to honor but to be honored himself. The 81-year-old is one of five artists recognized in the 44th annual Kennedy Center Honors, a celebration of lifetime achievement in the arts.

He will be fêted alongside comedian Bette Midler, Saturday Night Live producer Lorne Michaels, singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell, and Motown founder Berry Gordy.

The son of housewife and a university administrator-turned-professor, Díaz first started singing at age 8, at a Methodist school in his hometown of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

He was a boy soprano at the time—a far cry from the rich, velvety basso he boasts now—but his teacher recognized a spark of talent in his voice. She recruited him to sing the Stephen Foster song “Old Black Joe” at a parent-teacher association meeting.

It was the beginning of a lifelong passion for the performing arts. Díaz plastered his childhood bedroom with photos of Bob Hope and Kirk Douglas. He devoured records by Perry Como, Dinah Shore, Glenn Miller, and Frank Sinatra.

Díaz’s youth was split between San Juan and cities like Philadelphia and Cambridge, Massachusetts, where his father pursued degrees at the University of Pennsylvania and later Harvard. With no TV at home, his parents instead took him to see operas and plays in the evenings, at theaters like the Boston Opera House.

“I fell in love,” he says dreamily. “After my dad finished his studies in Harvard, we went back to Puerto Rico and I joined a choir.”

Even early on, Díaz started building the connections that would ignite his career. He took voice lessons from Puerto Rican soprano María Esther Robles. Fostered a friendship with composer Pablo Casals. Sang alongside opera icons like Richard Tucker.

Some of those relationships would span a lifetime. When Díaz made his San Francisco Opera debut as the lead in 1978’s Don Giovanni, he remembers that one of his teachers, Frederick Jagel, even attended the performance to cheer him on.

Díaz’s on-stage charisma and robust voice made him a hot commodity for opera companies around the world, from La Scala to Covent Garden. But no matter where he was or who he was with, Díaz says he found a home in the arts.

“To me, everything is translated into love. I love music. I love what I saw. I love what I heard,” he says. “At the end of the day, the international language is music. It is so easy to communicate through art.”

Now, in a new interview, he shares a glimpse at his career—and how his fellow artists played a role in his success.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: I know that, at age 16, you were singing in opera choruses in Puerto Rico.

DÍAZ: Yeah.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: Can you tell me about your first time performing in an opera?

DÍAZ: It was like somebody hit me over the head with a bat. I was enamored, literally enamored. When I was done, I stood there. We had learned music, and it was beautiful.

The repertoire was La Traviata and La Forza del Destino, and Madame Butterfly, Andrea Chenier, Faust, Carmen. You know, the bread and butter. And the first opera, the first rehearsal where I was on stage, was La Forza del Destino. I had a lot of participation in the chorus. There were a lot of choruses in that opera. And of course the great Jerome Hines was the bass then. I was in the bass section, and he was Il Padre Guardiano in the opera.

When I sang those choruses in La Forza del Destino and I heard this fantastic bass voice that was coming out of Jerome Hines—he was like six, seven feet tall—I said, “Oh my God, this is it. This is it.” I began to hint that I wanted to go somewhere that has a nice conservatory. Because, in Puerto Rico at the time, we did not have a conservatory yet.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: What I heard is that you dropped out of the New England Conservatory of Music to pursue a professional career. Is that true?

DÍAZ: Yeah. I was a kid. I was 22 years old or 21. And I started to talk to people who lived in New York. That was the place to go. I couldn’t really stay as a student because I was not proficient in piano. Academia demanded that I play the piano, that I was good in harmony and theory and all those things.

[The head of the conservatory's opera department Boris] Goldovsky said to me, “Look, frankly, you don't need this, Justino. You don't need to go through this. You have an ear. You learn roles. You know languages. Italian is very easy for you. You have a fantastic ear.” He intimated all these things. He didn't have to say them like that.

So I went to New York, and I sang for an agent. And by the third piece I was singing, he said, “Go ahead. I’m going to my—.” This was in his living room. He had a huge apartment in New York, but he went into his office adjacent to the living room and he made out a contract for me. “Okay. I'm going to be your agent.”

And slowly I began to get jobs everywhere: with ensembles, small symphony orchestras, oratorios societies, et cetera. I had to go. You said, why didn't I finish my studies? Because I was not your typical conservatory student.

There is no teacher like experience: getting up in an opera house and singing. One thing led to another. I filled in the blanks to audition at the Met yearly—

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: —National Council Auditions.

DÍAZ: Auditions of the year, that’s what they used to call them. I won first prize. One thing led to another, and that was it. And part of that first prize was a contract.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: I want to ask you about your mindset when all this is happening. You win the yearly auditions—the National Council Auditions—and then suddenly you're 23 years old and you have a contract with the Metropolitan Opera, which is insane to think about.

DÍAZ: Tell me about it.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: The fame or the pressure—how did that affect you when you're only 23? Or did it just glide off your back?

DÍAZ: I was so busy, so involved in my opera world, in my music world—learning, learning, listening, going to performances. I missed everything that was going on around me. I only vaguely remember Elvis Presley and then later on the Beatles. Nothing around me mattered except the music.

I started to sing in several important opera companies like the American Opera Society where [soprano Joan] Sutherland sang a lot. And Marilyn Horne. All the great singers sang there, and they sang repertoire that was not usually done by the Met or the City Opera.

I sang a few performances there, including getting to meet Igor Stravinsky when I sang the little, tiny role of the gravedigger in The Rake’s Progress. A lot of wonderful conductors heard me. [Thomas] Schippers, for example.

The music family is very small, in essence. So you become friends—or at least, friendly—with big-name stars. Word starts getting around. And unbeknownst to me, all these people I came in contact with started talking about me or recommending me. Even mentioning my name, that helps a lot. Many times, that helps much more than me going and singing for them.

My first Escamillo on stage was with [famed conductor] Herbert von Karajan, for crying out loud. And he hadn’t heard of me before we started rehearsals. That’s unheard of. But coaches at the Met had talked about me, and they said, “Yeah, listen to this guy. He’s going to be good. This is what you want.”

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: I’ve got to ask you: You’re still in your twenties when you're inaugurating the new Metropolitan Opera House with Leontyne Price.

DÍAZ: Yeah, it is crazy.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: Can you tell me about how that came to be? Where were you when you found out that you were in the running for the title role in a world premiere opera by Samuel Barber that was going to open the Metropolitan Opera House?

DÍAZ: Well, you don't really know how it happens. I got a note in my box at the Met, saying, “Make an appointment to see Mr. Bing [the Metropolitan Opera’s general manager] as soon as possible.” And of course, I did.

Back then, the Met was very tiny. Everybody was pushed together in little tiny offices, and there was a slightly bigger office where Rudolf Bing was. And he says, “Well, we have decided. Samuel Barber and Franco Zeffirelli have heard you sing.” I had already done Méphisto in Faust and Abimélech in Samson and Delilah and Sparafucile [in Rigoletto].

“Samuel Barber wants to meet you, the composer, and he wants to go over a few passages.” And I went to see Sam on the East Side, to his apartment.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: What was your first impression of Samuel Barber? I mean, holy cow!

DÍAZ: Well, you’ve got to realize that I didn't really realize how big and how important these people were. Yes, I had heard of Samuel Barber. I had heard of him, but the implications!

It just went right over my head. But in no way, mind you, did it go to my head. I always thought that, my God, I was very lucky.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: So the pressure didn't affect you.

DÍAZ: No.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: You were just so busy preparing?

DÍAZ: Yeah. In no way was I thinking that I was better than other people. I had no time for that. My energies were all taken up with living up to the new responsibilities that were thrown at me.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: You must have had moments where something unexpected happens. Do you have any stories of onstage mishaps?

DÍAZ: Oh yes. But you’re not going to hear them. A lot of them are X-rated. [Díaz chuckles.]

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: You have nearly a half century of singing—of active singing.

DÍAZ: Yeah. The reason I gave up: I was only 63. I say “only” because my voice was intact, except I started to have some health problems. At 55, I had a heart attack and open-heart surgery, four bypasses. After that I came back and I was still singing quite well. And then I got cancer. I got cancer of the colon. That happened. Then I started to take chemotherapy. And then I got the cancer of the lung. And then I got a hernia. My God.

I never talk about my illnesses or why I did something or the other, because I have a great ability to just put things out of my mind that are not pleasing. I don’t want people feeling sorry for me, first of all. Nobody likes that. And I don’t want to blame anything else.

What I did and what I achieved was due to my efforts and the luck of pleasing the conductors and the people who moved all the chess pieces around. Nobody does anything in a career in music alone. You meet so many great people who end up finally enriching your life beyond your imagination.

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: You've played so many roles, from Don Giovanni to Escamillo [the bullfighter in Carmen]. I wonder: Did you ever have a favorite role?

DÍAZ: I love the ones that offered an opportunity to act, roles that really had depth to them. Don Giovanni, of course. A lot of the Shakespeare characters. Macbeth to me was wonderful, wonderful. And Julius Caesar! All those big guys. Antony, even—although he was not necessarily a wonderful human being, historically.

Leontyne [Price] told me once, “You know, Tony—.” She called me Tony ever since we did the opera [Antony and Cleopatra].

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA: She called you Tony?

DÍAZ: Yeah. For Antony. “Hey Tony!” She told me: “Every time I go by Lincoln Center, I say, ‘Hello there! Remember me? I opened you!’”

I thought: What a wonderful quote. I said, “Leontyne”—we used to call her Lee—“I’m going to steal that from you. I’m going to say, ‘Hey, I opened you!’ in Lincoln Center.” So Leontyne and I opened the new Met. That was pretty big stuff.

The Kennedy Center Honors, celebrating bass-baritone Justino Díaz, airs on CBS Wednesday, December 22, 2021. For more information, please visit: https://www.kennedy-center.org/whats-on/honors/