‘Whoever Heard of a Chinese Bass?’ A Granddaughter’s Memories of Boundary-Breaking Performer Yi-Kwei Sze

Li is the granddaughter of bass-baritone Yi-Kwei Sze, widely considered the first Chinese singer to launch an international career on the opera stage—and the first Chinese singer to land a lead role in a major American opera house.

Sze made his U.S. opera debut singing the King of Egypt in 1950’s Aida at San Francisco Opera. He was also reported to be the first Chinese singer to have sung at Carnegie Hall.

But that knowledge would come later. At that moment, all Li knew was that she finally had a grandfather: a stonemason’s son, living across an ocean, far away in the United States.

Born in 1915 in Zhejiang province, just south of Shanghai, Sze was the second of two boys born to a well-to-do family. Shanghai was reaching its golden age, and the construction business was booming. Li would later learn that Sze’s father was responsible for cutting stones and building the banks and fancy edifices that lined neighborhoods like the French Concession.

But Sze had little ambition of following in his father’s footsteps. He later told newspapers that seeing the American performer Al Jolson sing at the movies made him want to sing too. By age 17, he was enrolled at Shanghai’s National Conservatory of Music, where he learned violin and voice.

It was an auspicious time to be an aspiring classical singer. Sze would be among the first generation of homegrown Chinese musicians to be featured soloists on Shanghai’s classical music stages.

Shanghai was a prized international port, situated on the coast at the mouth of the Yangtze, Asia’s longest river. Since the 19th century, American and European colonial powers had staked a claim to parts of the city.

And with that international presence came international music—including Western classical styles like opera. Shanghai was home to China’s first symphony orchestra. But institutions like that had historically catered to Shanghai’s Western audiences, showcasing lineups full of Europeans.

That started to change in the 1920s, ’30s, and ‘40s. According to Hong Kong music professor Hon-Lun Yang, the first Chinese soloist to featured with the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra—now the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra—was a 17-year-old violinist in 1929. That opened the door for more collaborations with local artists, including an emerging singer named Yi-Kwei Sze.

But though his career in the arts was progressing, back home, Sze faced family pressures. His father wanted to see him married—and he allegedly had very specific ideas about who would be the best candidate.

“His father never wanted his son to marry to Shanghai girls,” Li explains, relaying what her mother and uncle explained to her. “In Shanghai, girls were more fancy, in high heels, lipsticks, right? He didn’t like that. So both sons had to marry someone from the village he came from.”

Sze’s father thought he had found the perfect match in a young woman from the countryside named Yo-Yo Xing. “Everybody told me she’s the most beautiful girl in the whole area. And she was very mellow. She’s that type of typical Chinese ideal wife,” Li says.

The couple was married, and together, Sze and Xing returned to Shanghai. Sze was studying with the Russian opera singer Vladimir Shushlin, one of the foundational figures in bringing Western opera to Shanghai. Li still remembers Sze could sing a fierce rendition of the Russian tune “The Song of the Volga Boatmen.”

But Sze hadn’t just found his voice at the conservatory. He found love there too. At the time, he and pianist Nancy Lee were only classmates, but Sze’s granddaughter Li suspects the two musicians forged a strong bond over song.

“They were like a really good match,” Li says. “They would just talk about music together, play together. One would sing, one would play the piano. They were always together.”

Li’s grandmother Xing couldn’t compete. “My grandma also had this gap with Yi-Kwei. She didn’t understand what he was doing,” Li says. He would talk about music, but she couldn’t follow.

Li believes her grandparents did care deeply for one another. But the differences in their education and interests were too great for them to have the kind of love Sze and Lee had.

“My mom said earlier, before the Communists cleared everything, she remembered in the house they had some cards made by Yi-Kwei,” she explains. “One side was a picture, and the other side was a Chinese letter. My grandma told my mom that he was using that to teach my grandma to read.”

And then came the event that would scatter their lives forever. The Japanese launched a full-scale invasion of China in 1937, marking the start of World War II for the country. Shanghai was among the cities that fell to Japanese control.

With much of the eastern seaboard under Japan’s rule, Chinese forces moved inland, relocating the country’s capital to Chongqing.

Sze’s star had already been on the rise: His granddaughter Li learned from family members that he had sung for Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek’s birthday just prior to the invasion. Both men were from Zhejiang province, and his voice left a favorable impression.

With his voice starting to win fans, Sze toured Hong Kong to raise funds for the resistance against the Japanese. But in 1941, he was forced to leave: The Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor, and Hong Kong surrendered to Japan.

“The Japanese cut all the transportation, waterways, and stuff,” Li says. “It took him two months to take the side roads to travel back to Chongqing.”

By that point, Li’s grandmother Xing had three children, the eldest of whom was Li’s mother, Meiyi Sze. They had taken shelter in the countryside to evade the Japanese. The years they spent apart had brought Sze and the pianist Nancy Lee closer.

Toward the end of the war, Sze announced his intention to be with Nancy. He left for the U.S. in 1947, joining Nancy, who had left shortly prior.

“My mother was 13 when Yi-Kwei left. She was like, my grandma always had tears,” Li says.

“At the time, Chinese culture was really cruel to women. If your husband leaves you, you never get married again.”

Two years later, the Chinese Communist Party gained control of mainland China. The Cold War had already begun. And the Korean War in 1950 would put the United States and China on opposite sides of the battlefield.

The ongoing international conflict made it impossible for Yi-Kwei to connect with his family back home in China, and vice versa. No mail could pass between them. “For many years, both sides don’t know how the other side is doing,” Li says. “It was like 20-some years he was totally silent.”

But while little news was reaching China, Sze was making headlines in the West. As soon as he arrived in 1947, the 31-year-old Sze held a recital at the historic New York City concert venue Town Hall. Nancy Lee Sze accompanied him on the piano.

“His singing at this debut had unique interest since vocalists from China, and especially those with deep voices, rarely have appeared as recitalists in this city,” The New York Times mused in its lukewarm review.

That fixation on Sze’s race and nationality continued, especially in the early years of his career. The ABC Weekly—a publication from the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC)—captured the contradictory attitudes toward his identity in its profile of the artist.

Sze, the Weekly claimed, “is so wholeheartedly accepted for his voice that his nationality is only an accidental characteristic. Nevertheless, he is expected to have Chinese songs in his repertoire and from time to time sing in Chinese. Just as [soprano Elena] Nikolaidi is not allowed to forget she’s a Greek and as negro spirituals are expected of Dorothy Maynor.”

The Weekly also described the hesitations of San Francisco Opera company founder Gaetano Merola, upon meeting the young bass-baritone. “Why does a Chinese want to sing opera?” Merola reportedly exclaimed. “Whoever heard of a Chinese bass?”

Still, Merola came to prize Sze and his “voice of pure velvet,” as one San Francisco Chronicle critic called it.

“Yi-Kwei Sze is apparently Merola’s own carefully guarded secret,” the Chronicle wrote in 1950. “His reply to questions concerning the singer only succeeded in establishing that he is Chinese, comes from Shanghai, knows many roles, and is one of the most musical singers Merola has ever heard.”

But the public still gaped over Sze’s identity as an Asian man. Though San Francisco Opera was expecting other debuts in its company that year, the Chronicle made special note that “perhaps the most unusual of these artists is Yi-Kwei Sze, who comes from the Municipal Opera in Shanghai.”

Still, more contracts came. More performances. He even made record deals. Sze was swiftly becoming one of the great bass-baritones of his day, no matter his race. He met John F. Kennedy. He taught at universities. He became an ambassador for opera across the United States and Europe. And he and Nancy Lee Sze welcomed a baby boy, named after the musician Alexander Kipnis.

But back home in China, life was changing just as swiftly. In the early days of the Communist regime, Western classical music had been taboo. “Myself, I know nothing about music,” Li says. “When I was a kid, I’d never even seen what a piano would look like.”

The family’s former wealth—and Sze’s fame in the Western world—were likewise subject to scrutiny. Communist leader Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution had made displays of wealth dangerous. The “Four Olds” had to be purged: old culture, old ideas, old customs, and old habits.

“I had a little winter jacket that was made from my grandma’s old qipao,” Li recalls, using the word for a traditional Chinese dress. “But I had to put on a really ugly shirt outside, because I couldn’t let people know I had that nice thing passed down from my family.”

Li says she spent part of her childhood in a labor camp. Li’s mother had been a college professor and agricultural mechanical engineer working in a rural village near Beijing. When she witnessed starvation conditions among its residents, she wrote a letter on their behalf. It got her labeled anti-Communist, Li says.

But when U.S. president Richard Nixon arrived in China in 1972 to normalize relations with Mao Zedong, things started to change for Li. She says she was 14 when her mother finally felt comfortable telling her about the extent of Yi-Kwei Sze’s singing career. Eventually, international relations relaxed enough for Sze to come visit.

Li says he had been trying to get in touch with the family for years—but returning was out of the question. He feared imprisonment or worse.

But with diplomacy restored between China and the United States, athletes, artists, and intellectuals started to travel back and forth between the two countries, as a sign of friendly relations. Yi-Kwei Sze is thought to be among the first American artists to arrive in China to teach voice lessons during that time.

Li remembers waiting for him to land in Beijing. She had never seen an airplane before, and the airport was tiny compared to today. “There were only two rows of chairs,” Li laughs.

The man who arrived was a foreigner to Li. Yi-Kwei Sze stepped off the plane in a suit. He was nice to Li, cracking jokes, laughing. But there were cultural differences. Li says the family had been instructed to avoid topics that could be politically sensitive, and Sze couldn’t understand why they wouldn’t speak more freely. He also scolded Li’s younger brother for slurping his soup, a taboo more common in the U.S. than in China.

“And then he also spoke with a Shanghainese accent. And sometimes he had trouble to understand me. I had trouble to understand him. But he was really, really nice to me,” Li says.

“Even though he’s Chinese, I feel like he’s not a Chinese, you know? The way he talks, the way he dresses, everything is so different.”

And he came laden with gifts from the family he hadn’t seen in decades. There were suitcases full of basics, especially fabric and clothing. And eventually, he sent each household a color TV, the latest model from Japan. Li still treasures the wool blanket Sze gave to her grandmother, who then passed it down to her.

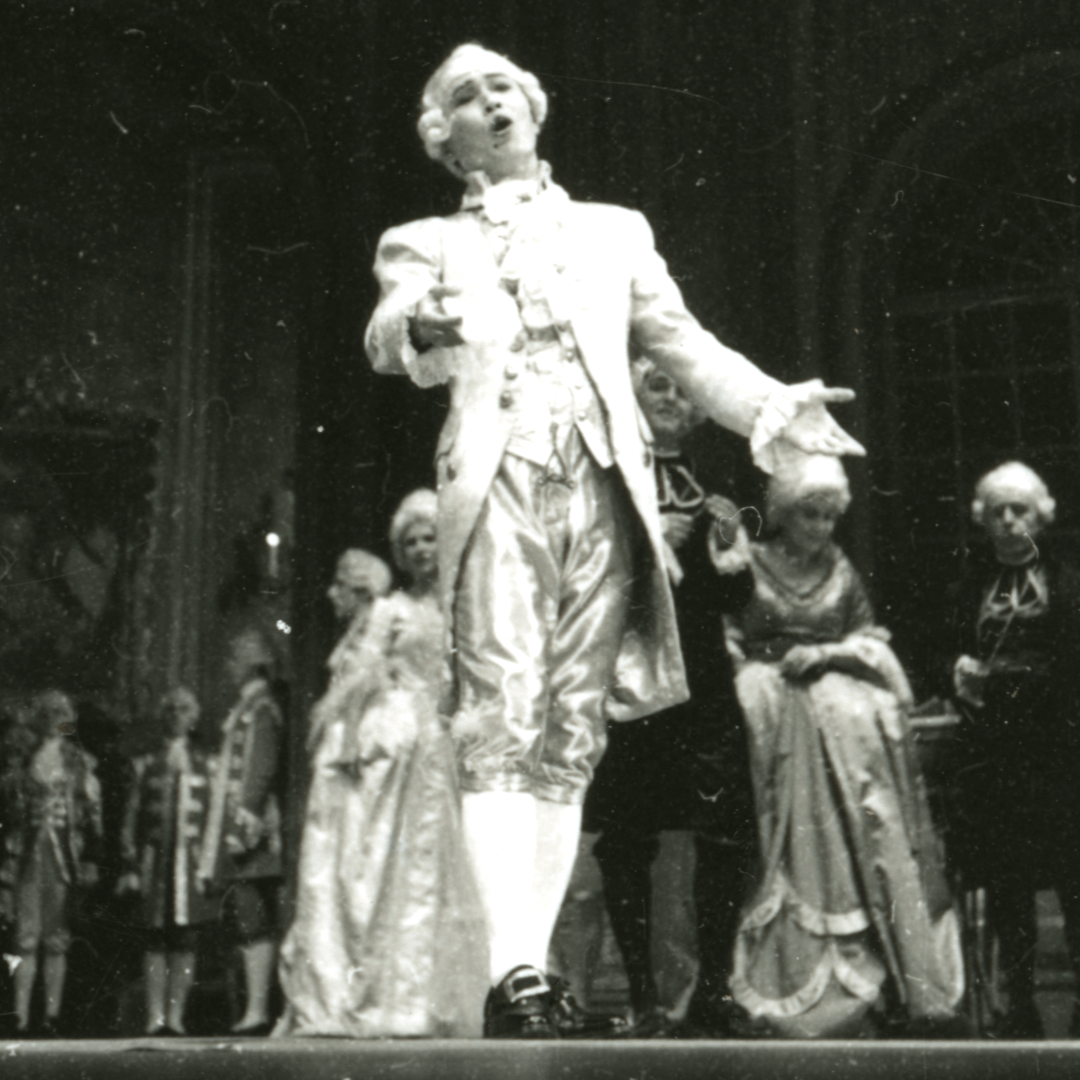

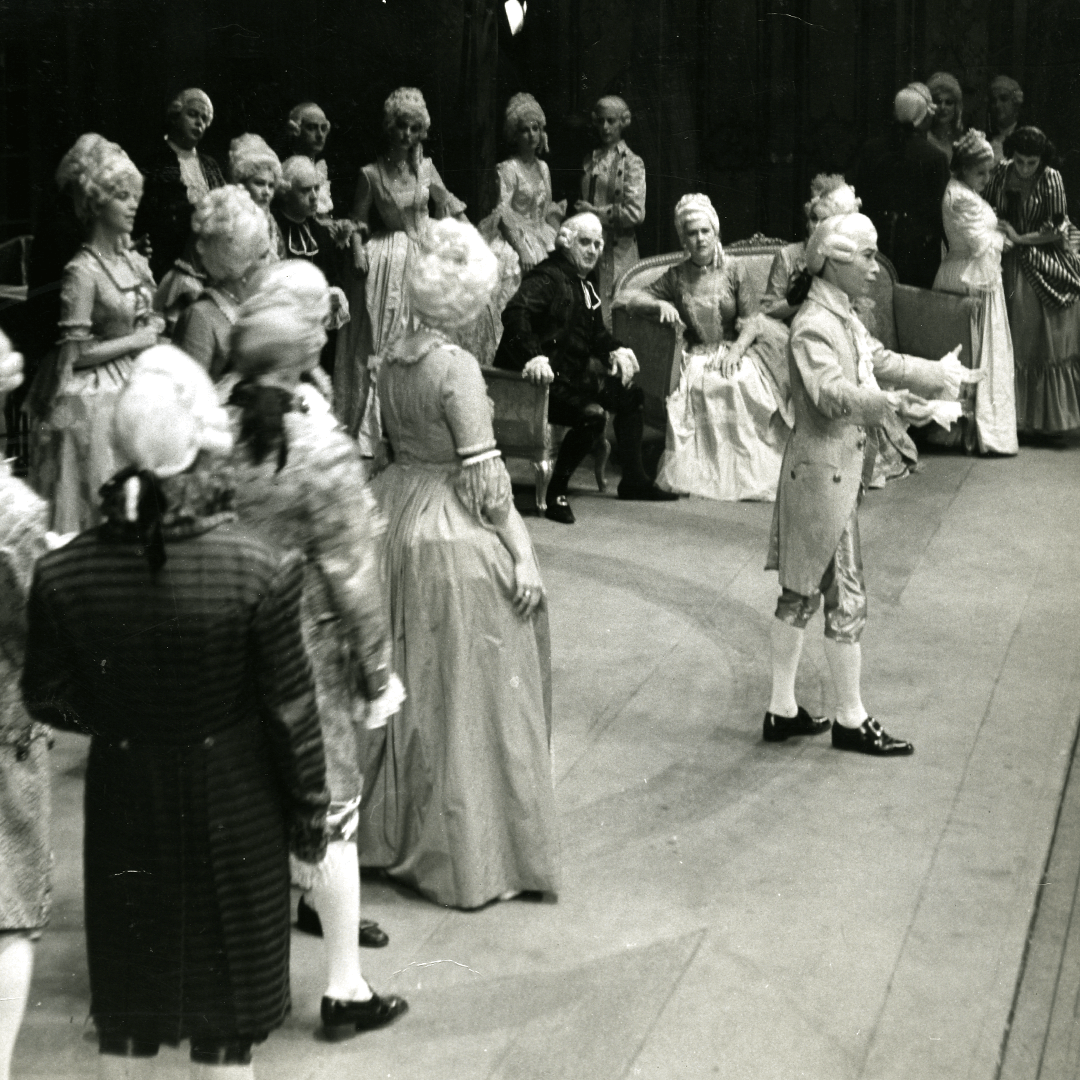

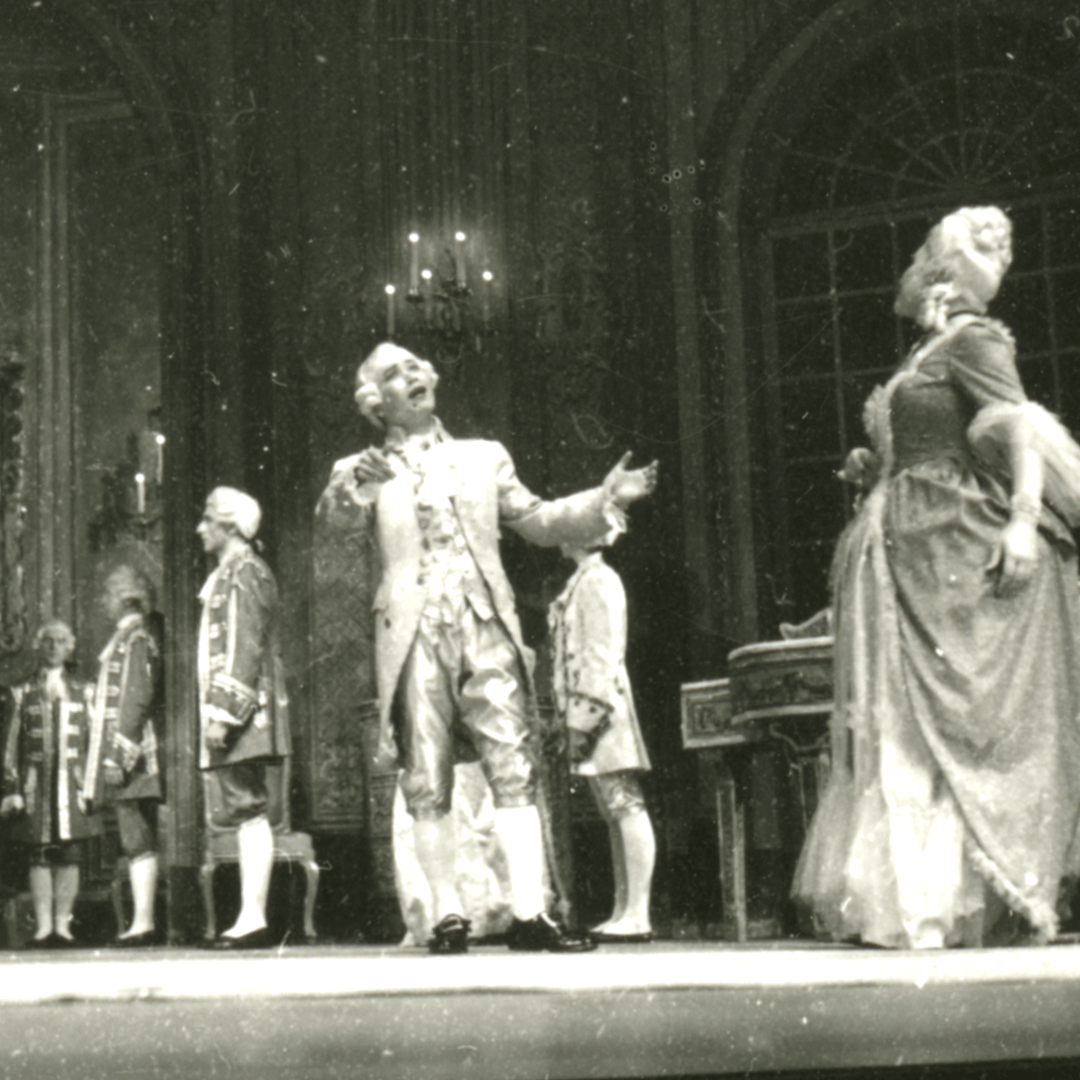

She also got a chance to see him perform on that visit. “I had no idea what he was singing, but I remember his expression was so amazing. Every part of his muscles also sang with him,” Li says.

Li came away with the impression of a man full of art. Not only did he sing, but he loved to cook and design his own pillows and curtains. She also saw how he loved his family. When Li’s grandmother Xing was in failing health, diagnosed with cancer, he sent everything she needed to get the best medical treatment.

Sze passed away at his home in San Francisco in 1994, at the age of 78. Nowadays, Li herself lives in the United States. A software engineer living in Seattle, Washington, Li has traveled the globe learning about her grandfather’s legacy. She even went to Germany to recover recordings an Yi-Kwei Sze fan left her in her will.

There are so many mysteries Li has yet to unravel. Li says she’s always wondered how Sze managed to achieve the level of artistry he did: Was it natural talent? Practice? A combination of both?

But when Li looks at her own daughter—a writer who loves journalism, film, and photography—she feels encouraged to keep searching for answers. After all, she sees in her grandfather the potential to inspire future generations, to teach artists like her daughter a simple lesson:

“When you do things good, no matter what the optics are, you still can get there.”