Unfinished Work

The greatest art, Herman Melville believed, remains unfinished, awaiting posterity to unearth its secrets. Moby-Dick—“the draught of a draught,” he called it—proved his point. Virtually ignored on publication in 1851, it followed most of his novels in dropping out of print, a collective failure that led him to abandon fiction for poetry. Then, in 1888, something compelled him to start a new novel, Billy Budd. “God keep me from ever completing anything,” he had written in Moby-Dick about the paradox of big aspirations. Now the almighty took him at his word. Melville’s death in 1891 arrested Billy Budd’s gestation. The manuscript, a jumble of bad penmanship, strike-throughs, additions, and interpolations, remained a mess that no one except his widow knew existed.

By 1919, with a Melville revival underway, the scholar Raymond Weaver planned the first biography of the novelist. In his research he combed through Melville’s papers. Among them he uncovered Billy Budd—for a literary specialist, a find analogous to stumbling upon Machu Picchu or excavating Tutankhamun’s tomb. He worked fast to share his discovery.

Unfortunately, he worked too fast. Errors large and small riddle his Billy Budd edition of 1924, and many of these were repeated in 1948 in what claimed to be the “first accurate transcription.” Not until 1962 did the now-standard version appear. Its editors prepared their text with the care of detectives, and their investigations revealed that, every time Melville believed he had finished the manuscript, he found more to revise. “What still further changes he might have made had he lived,” they admitted, “are of course conjectural.”

Conjecture propelled the work of E.M. Forster when, in 1949, working with Eric Crozier (who contributed theatrical expertise), he began transforming Billy Budd into a libretto for Benjamin Britten. Forster, among the 20th century’s pre-eminent English novelists, knew music well, and we can thank him for making Benjamin Britten an opera composer. Britten in 1941 chanced upon a Forster article that sparked his interest in the Romantic poet George Crabbe. “In a flash I realized … that I must write an opera,” Britten recalled of his encounter with Crabbe’s The Borough. That poem inspired Peter Grimes, which premiered in 1945 and changed the trajectory of Britten’s life. A friendship developed between composer and writer. Soon, to Britten’s delight, Forster suggested he might try his hand at a libretto.

Forster adhered to much of what he found in Melville. But while Melville’s editors rebuilt a novel from what they discovered, Forster used Melville as foundation for a new edifice. To criticize it for divergences from its source is to ignore that the opera, while true to Melville’s outline, is not Melville’s. Besides the Act Two pursuit of the French frigate, an action sequence absent from the novel, Forster’s major inventions are a prologue and an epilogue that frame the action and enable him to tell the story from Captain Vere’s perspective, unlike Melville, who uses an omniscient narrator.

Forster also brought his sensibilities to Melville’s tale. He believed Billy Budd offered the opportunity to be candid about homosexuality. That subject inevitably surfaces in discussing the opera and the novel. You might agree it exists in Melville’s book, but only if you look, and look closely, and Britten’s reluctance to look closely disappointed Forster. Melville, a sailor in his young years, understood how long sea journeys and cramped quarters can ignite carnal instincts in men confined to each other’s company. He touched on this in his 1850 book, White-Jacket. There the narrator makes clear he doesn’t share this orientation, but even if we assume he speaks for the author, we should remember that Melville possessed human sympathies uncommon for his or any time. In Moby-Dick, Ishmael and Queequeg share a bed—a pairing of necessity, not sex—enabling Melville to emphasize that humans of every color and faith are “wedded,” as Ishmael says. Melville wrote openly and with no embarrassment about men’s affection for one another. Best not to mistake his artistic stratagems for a preoccupation with the intimacies of male bonding. While much is made of Billy’s physical beauty, that beauty is emblematic—not of Eros, but of innocence. John Claggart intends to destroy Billy not because his advances have been rejected—he makes none—but because Billy’s goodness offends him. Descended from Paradise Lost’s Satan, Claggart is a psychopath, dispensing evil because he can. He likes Billy’s looks but despises what they signify. When he calls Billy “handsome,” Claggart is stating a fact, not proposing a hookup.

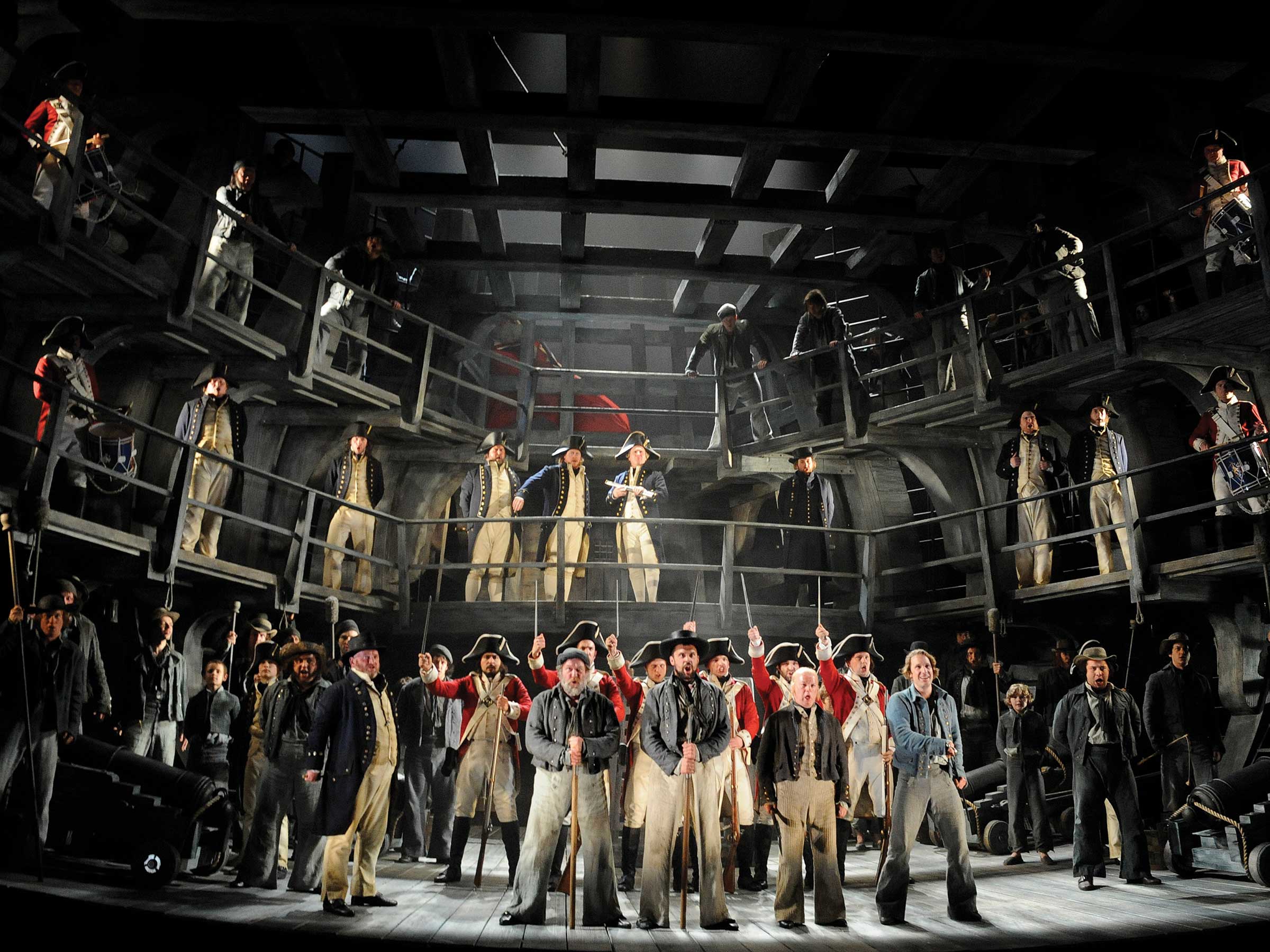

In dense prose, and as gingerly as a cardiologist threading a scope through an artery, Melville explores the minds and motivations of Captain Edward Fairfax Vere and Master-at-Arms John Claggart. He called this deliberate drama “An Inside Narrative.” Translating it to the stage demanded much from the librettists but more from the composer, and Britten reveled in the challenge (“I’ve never been so obsessed by a piece”). The music bears responsibility both for psychological penetration and dramatic movement. In Britten’s hands, everything springs to life from the first scene on deck, where he infuses mundane phrases with energy and ignores the bar lines’ limits, enlivening nautical references and commands and even conjuring the ocean’s mystery (as in the chorus “O heave! O heave away, heave,” kin to Dawn, first of Grimes’s Four Sea Interludes). Immediately Britten plunges us into the world of a British man-of-war, circa 1797. Using only male voices and weaving them into an orchestra lit with brass and high winds, Britten creates a continuously varied sound texture.

The score abounds in thematic correspondences across its span. The slow pianissimo string figure we hear at the outset, and which recurs in the epilogue, generates such variants as the forward-thrusting figure at the first mention of Claggart’s name, the bass clarinet line that snakes beneath Claggart’s accusation to Vere, the strings’ nervous pulse as Billy defends himself to the drumhead court, even the fanfare that drives the sea chase.

Embracing Melville’s pessimism, Forster and Britten portray the perils of innocence. A stammer plagues the apparently undefiled Billy and turns this angel into a murderer, striking him mute when challenged, able only to counter false witness with a primitive response, a killing blow of his fist. In the fallen world, the cards are stacked against innocence, and self-defense is its undoing. Claggart serves as the universe’s instrument to annihilate Billy. At his death the burden passes to Vere, who accepts responsibility while tortured by the justice he feels forced to dispense. “Beauty, handsomeness, goodness,” he laments, echoing Claggart, “it is for me to destroy you.”

Among the puzzles and triumphs of Melville’s novel is the scene in which, having agreed with his officers that Billy must die, the captain disappears into an anteroom where Billy waits. “Beyond the communication of the sentence,” writes Melville, “what took place at this interview was never known.” The tale’s narrator goes so far as to imagine that Vere “may in the end have caught Billy to his heart.” Who can say? “Holy oblivion providentially covers all at last.” Vere’s disclosure of the verdict and Billy’s reaction remain private. Words failed Billy at his crucial moment. Words fail Melville now. Nor did Forster invent words for a scene that remains unseen. The music communicates a numinous solemnity. For three minutes that feel timeless, the orchestra takes over. Group by group, brass, strings, winds, and horns take turns playing a series of common triads—a radiant, chorale-like sequence spanning 34 bars. The writer Donald Mitchell believes that Britten envisioned a scenario, “each chord…within the total arch [representing] a stage in the development of the encounter between Vere and Billy.” Here, Mitchell concludes, “music speaks in a tongue for which words could never be found.” These same chords return in Billy’s last monologue, when, section by orchestral section as in the interview sequence, they accompany him as he sings, “I’m strong, and I know it, and that’s enough.” Once more the chords sound, now in the epilogue, as Vere adopts Billy’s words: “I’ve sighted a sail in the storm, the far-shining sail, and I’m content.”

A forced optimism, at extreme odds with Melville, seems to inhabit the epilogue. Yet the chords of the interview sequence rising through this scene suggest a recurrent Melville theme: salvation through human empathy, the empathy those chords represent. At last, after a surge of affirmation, the orchestra falls silent, the captain’s words end in a mutter, and the opera concludes, not quite sure of what has transpired in these final moments.

Critical response was mixed when Billy Budd premiered, on December 1, 1951, at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. Nine years later Britten compressed the original four acts into two, tightening the structure and quickening the pace. The art historian Kenneth Clarke may have gone too far in calling the opera “one of the great masterpieces that change human conduct,” but Billy Budd lodges in the consciousness, where it keeps doing its work. Like Melville’s story, the opera’s enigmas invite continuing interpretation. In that sense it remains unfinished, as Melville might say, and as such it proves most true to him.

Larry Rothe writes about music for San Francisco Opera and Cal Performances and has written for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, and San Francisco Symphony. His books include For the Love of Music and Music for a City, Music for the World.