Setting Sail with Billy Budd: A Selective Overview of the Opera’s Production History

From the perspective of directors and designers, a merely realistic presentation of Billy Budd’s 1797 British naval setting, however technically impressive, would reduce Britten’s unsettling masterwork to a superficial period piece—an Aubrey–Maturin tale set to music. Any honest attempt to grapple with the substance of this opera must balance the literal mise-en-scène with its multiple layers of significance—psychosexual, social, jurisprudential, metaphysical, even theological. These layers are interconnected but in some ways also contradictory, thereby reflecting the divergent outlooks of Britten and his librettists, E.M. Forster and Eric Crozier (and of Melville).

In the face of these challenges, it is all the more remarkable that Billy Budd has fared so well in its production history. The producer Basil Coleman and designer John Piper articulated their intention to bring out both realistic and allegorical-symbolical dimensions—what they termed the opera’s “dual planes”—in discussions before their staging of the world premiere at London’s Royal Opera in 1951. They accomplished this by contrasting realistic shipboard details with a suggestive pitch-black background hinting at the mythic, open-ended aspects of the opera.

In response to some stern objections from eminent critics, Britten used the occasion of a BBC broadcast in 1960 to prepare a substantial revision, streamlining Billy Budd from its original four acts (with three intermissions) to the tighter two-act version most frequently encountered since. Again, Coleman and Piper were charged with preparing the revised Billy Budd’s stage premiere (at the Royal Opera in 1964). According to Porter, Britten wanted less “shipboard detail,” so Piper’s designs were “stripped and simplified.” Still, with its balance between realism and abstraction, the overall approach of the original Royal Opera productions (for the four- and two-act versions alike) established a kind of template for stagings of Billy Budd that has had a long afterlife.

The gap between the 1951 and 1964 London Billy Budds is a characteristic of the opera’s reception history. Landmark productions have typically been followed by periods of hiatus. In the United States, Billy Budd was initially seen in 1952 as a live NBC-TV transmission of excerpts from the score (limited to 90 minutes)—the first Britten opera to be televised and, in its own right, an important chapter in the history of the medium of television opera. A single performance took place later that year at Indiana University, but it was not until 1970 that the two-act version received its U.S. stage premiere at Lyric Opera of Chicago. (A concert performance of the revised opera was led by Georg Solti at Carnegie Hall in 1966.)

There was another gap before the next flurry of stateside interest in Billy Budd, which was presented in company premieres almost simultaneously at San Francisco Opera and the Metropolitan Opera in September 1978—to some extent stimulated by landmark stagings of Peter Grimes in America (including SFO’s company premiere of the opera, produced by Geraint Evans, in 1973).

The first Billy Budd at the War Memorial Opera House was directed by Ande Anderson, who had worked with Britten on the original London production (he also staged the Chicago premiere). It represented “more or less a reconstruction of the 1951 approach,” according to the scholar Mervyn Cooke. In his joint review of the bicoastal Billy Budds, Porter wrote that the sets effectively rebuilt Piper’s original designs “on a larger scale and provided [them] with projections of changing sea and skies.”

Incidentally, a line Porter quoted from Melville’s tale acquires a poignant dimension if we recall that just a few months before San Francisco’s 1978 premiere, the rainbow flag had first been introduced at the Pride Parade: “Who in the rainbow can draw the line where the violet tint ends and the orange tint begins?” Despite recurrent critical hedging about the significance of gay subtexts in both the novella and the opera, Forster was especially outspoken about his interpretation in a letter in which he found fault with Britten’s music for Claggart’s monologue (“O beauty, o handsomeness”): “I want passion—love constricted, perverted, poisoned, but nevertheless flowing down its agonizing channel; a sexual discharge gone evil.”

Meanwhile, the Met expanded on the production John Dexter had first tried out in 1972 at Hamburg Staatsoper, using William Dudley’s striking visualization of the HMS Indomitable, against a black background, as a vast lateral cross-section. Hydraulic stage technology allowed the ship’s levels to rise and fall, expand and contract, thus creating spaces in which Dexter could carefully delineate “the symbolic heights and depths of the opera in clear visual terms,” as the Britten expert and protégé Donald Mitchell puts it. Dexter’s production has been periodically revived by the Met (most recently in 2012). Porter extolled the Dexter staging as “scenically the more spectacular and emotionally the more romantic, while San Francisco’s [conducted by David Atherton] was musically in sharper focus—the clearest and keenest account of the opera I have ever heard.”

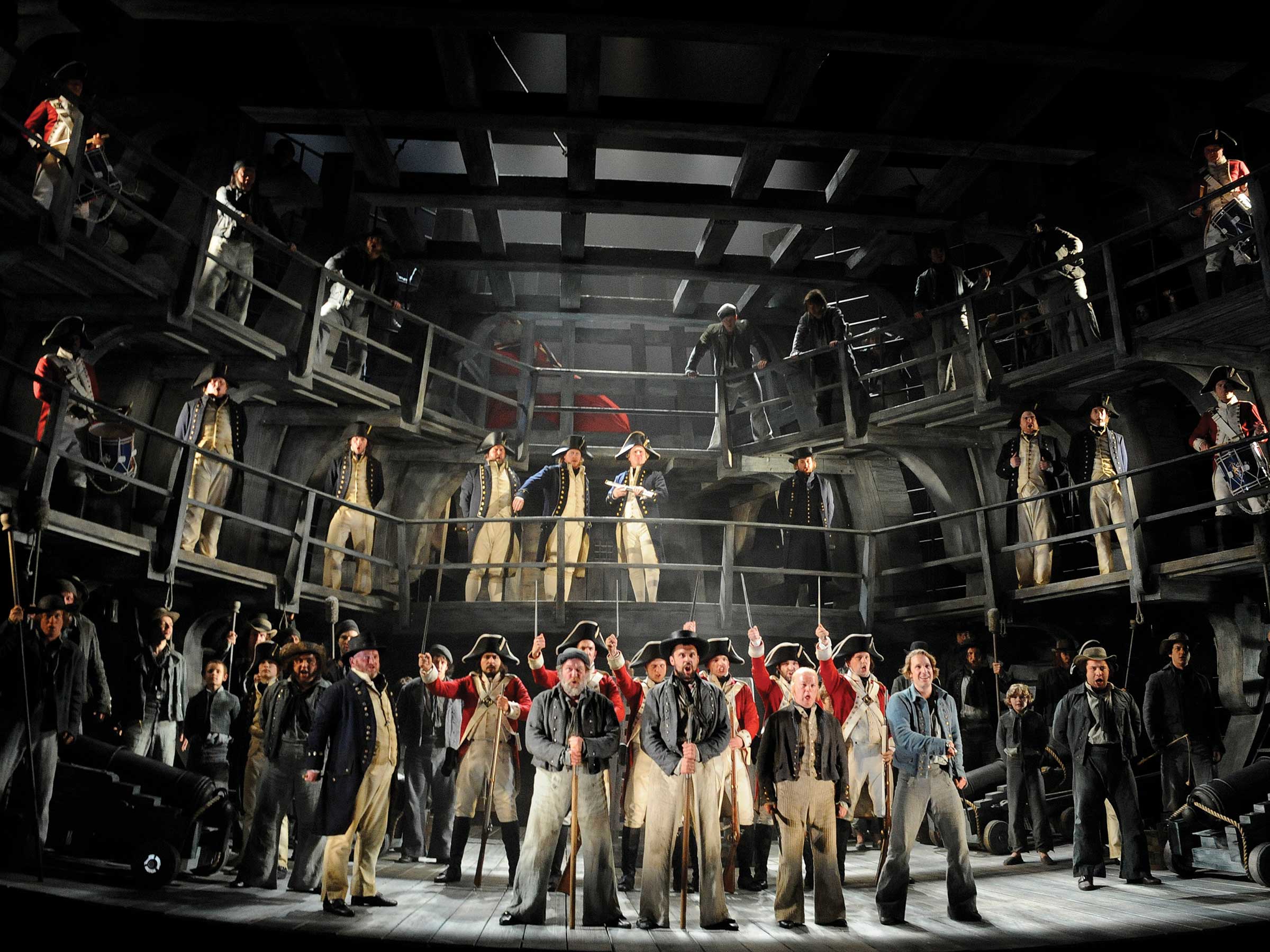

But New York offered a competing vision of the opera in 2014 when Michael Grandage’s staging, introduced at the Glyndebourne Festival in 2010 (and his first foray into opera direction), made a stop at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. (With this presentation at San Francisco Opera, Grandage’s critically acclaimed production receives its West Coast premiere.) The careful details of Christopher Oram’s curved, wooden ribcage set (making reference to another Melville icon with its suggestion of a whale) have been praised for persuasively evoking a sense of the historical period as well as the claustrophobic spaces in which the story’s psychodynamics play out—all of a piece with the director’s stated aim to give voice to the ideas “that were clear to the creators” of the work. David Patrick Stearns hailed the BAM revival for “exploring the musical and dramatic layers of Billy Budd with a thoroughness and balance not often found anywhere.”

Like a theatrical version of punctuated equilibrium in evolution, anniversary years have prompted sudden fresh approaches to Billy Budd after periods of dormancy. To mark the opera’s 50th anniversary in 2001—and, as it happened, in the wake of 9/11—new productions surfaced in Chicago, directed by David McVicar (with Nathan Gunn taking on what has become a signature role), and in Vienna, where Willy Decker brought back the original four-act version, relying on a radically simple, raked staging.

Following a revival of the 1978 production in 1985 (then directed by Basil Coleman), San Francisco Opera chose Decker’s version for its most recent staging (in 2004—Donald Runnicles conducted the production both in Vienna and in San Francisco). The Decker production also had the honors of introducing Billy Budd to the Russian stage in 2013, the centennial of Britten’s birth, when it was performed at the Mikhailovsky Theater in St. Petersburg.

Another milestone production is the one Francesca Zambello directed at the Royal Opera House in 1995, with Alison Chitty’s vertical designs memorably delineating the ship’s power structures. “In an isolated society, like ships or prisons, certain men become the females of that world,” Zambello observed. The critic Rodney Milnes remarked on the irony of an American—also notable as a woman directing Britten’s all-male opera—being the first to offer a new take on Billy Budd at Covent Garden since the premiere of the original and revised versions there: “Perhaps it takes an outsider … to turn the screws on us.” Zambello’s production has since been revived with widespread success at various American companies.

If the effort to find a balance between realism and abstraction is a basic constant in Billy Budd productions, the work has not remained immune to attempts to update the “realistic” side of the equation. David Alden’s 2012 production of the work for English National Opera, wrote London critic Andrew Clements, reimagined the action as taking place “in a rusting, steel-hulled vessel somewhere in Europe during the first decades of the 20th century, perhaps an early Soviet ship fighting a local war in the Baltic or the Black Sea, on which jack-booted officers maintain a regime of brutal suppression.” In 2007, for Oper Frankfurt, Richard Jones set his production in a naval academy in the mid-century period when the first Billy Budd was introduced. And already in 1987, Graham Vick’s production for Scottish Opera included designs outlining “a more modernistic structure of steel ladders and catwalks, perhaps intended to suggest the interior of a Victorian prison as much as a ship,” notes Mervyn Cooke.

After an absence of the work for almost two decades from the house that gave it birth, Billy Budd returned to the Royal Opera last season in a much-discussed new production by Deborah Warner. Using Michael Levine’s set design of floating deck platforms and rigging and Chloe Oblensky’s costumes, Warner blended references to the Napoleonic era with suggestions of the 20th century, while also giving Claggart’s role in the tragedy a provocatively fresh slant.

In this bicentennial year of Melville’s birth, the desire to unravel the meanings of the “Handsome Sailor,” the Iago-like Claggart, the maritime Pontius Pilate, Captain Vere—and all those aboard the metaphoric Indomitable—remains as powerful as it is elusive. Britten has revealed that some of the most resonant answers lie beyond words.

Thomas May is a longtime regular contributor to San Francisco Opera’s programs and the author of Decoding Wagner: An Invitation to His World of Music Dramas.