From Page to Opera Stage: Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette and Britten’s Billy Budd

Although Gounod’s opera largely follows Shakespeare’s action, the opera and the play display markedly different values in their treatment of romantic love. For a start, romantic love is but one part of the vivid tapestry of a late medieval society summoned up by Shakespeare in his tragedy. There can be no doubt that his sympathies lie with the two lovers—after all, he endowed them with some of the richest and most exquisite poetry he ever wrote—but our attention in the play is caught by so much else, above all, the violent conflicts of the Capulets and Montagues, the genial vulgarity of Juliet’s Nurse, the questionable motives of Friar Laurence, and the tyrannical atmosphere of the Capulet household. Although Romeo and Juliet’s love stands out for its purity and youthful idealism, it strikes us as frail and might, in due course, even be corrupted by the venality in which it must live.

Gounod’s dramatic landscape is radically different from Shakespeare’s. While in the play romantic love and the violent, volatile world of street fighting intertwine, in Gounod’s opera they are largely isolated from each other. The violence is confined primarily to the tempestuous prelude, which depicts a chaotic maelstrom of conflict, reaching a level of intensity that will never be attained on stage. In the early scenes, the ball especially, there are moments where passions threaten to break the festive surface, but Gounod’s librettists, Barbier and Carré, reduced the role of Tybalt, Shakespeare’s most violent figure, to just a few lines and left what rabble-rousing there is to the innocuous servant Gregory. As a result, the excessive hatred that drives Shakespeare’s action, is abated in the opera. It erupts once, in the crowd scene that forms the finale of act 3, when Mercutio and Tybalt are killed and Romeo banished, but this culminates in a solemn ensemble, which suggests that life in Verona is characterized by an oppressive unity, rather than formed by the vehemence of civil conflict.

All this highlights the salience of Romeo and Juliet’s passion. With the savagery of the family conflict distanced, the lovers come insistently to the fore. While Shakespeare does all he can to keep Romeo and Juliet apart—they are on stage together for only about ten percent of the play’s action—Gounod does all he can to bring them together. They are given four love duets—an excessive number even in Romantic opera—and are on stage together for a good forty percent of the action. As a result, it is the inviolability rather than the friability of romantic love that comes to the fore and marks the opera as a work unmistakably of the 19th century.

The central action of Roméo et Juliette is the comprehensive journey Gounod takes into the mentality of romantic love. The first duet, which parallels the formality of the sonnet form in the first meeting of Shakespeare’s lovers, has a poised, even reserved quality, as if the lovers cannot quite believe in the magic feelings they have aroused in each other. The long balcony scene, which moves from one melody to another, shows them exploring and confirming those feelings. But it is in the bedroom scene, which Gounod adorns with his lushest melodies, that Romeo and Juliet emerge as fully matured lovers; as they do we hear echoes of Berlioz’s great Roméo et Juliette symphony, which had a profound effect upon Gounod, as well as of Tristan und Isolde. In the final duet, in compliance with a good two-hundred-year tradition in both operatic and dramatic performance, Gounod has the lovers die together, not separately as in Shakespeare. In Shakespeare their deaths are lonely and bleak, in Gounod they ask for God’s forgiveness as if their love will find reward beyond the grave.

In actuality, the 19th century bourgeois family was only a shade more liberal than its 16th-century forebears had been when it came to the marriage of its children. But the myth of Romantic love as a transfiguring force, as the highest happiness humans can achieve, prevailed in the 19th century and operas such as Roméo et Juliette celebrated it.

While the action of Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette parallels that of Shakespeare’s play, Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd undertakes a wholesale reimagining of its source material, Herman Melville’s novella, Billy Budd. Britten’s choice of Melville’s story might seem to have been an odd one. On the page, few prose works seem to offer so little promise for stage adaptation as Billy Budd. This story of a charismatic and handsome young sailor who is wrongfully accused of fomenting mutiny on a British gun-ship during the Revolutionary wars, unintentionally kills his accuser and then is hanged despite his superior officers’ conviction that he is innocent, is a literary masterpiece. But it is distinguished not so much by its drama as by the extraordinary density of its language, the serpentine nature of its prose, and as a novella of ideas, centered on the clash between natural and military justice. The one character of whom we are constantly aware is the narrator himself whose main concern is to penetrate the intricate network of impulses, ideas, philosophies, and legal issues that create the enigmatic circumstances in which a man can be innocent and yet at the same time guilty of murder. The challenge set by the language and ideas is compounded by the novella being left incomplete at Melville’s death in 1891. It was only discovered in manuscript in 1919, and a reliable text was not produced until 1962, a good eleven years after Britten’s opera was first performed at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in 1951.

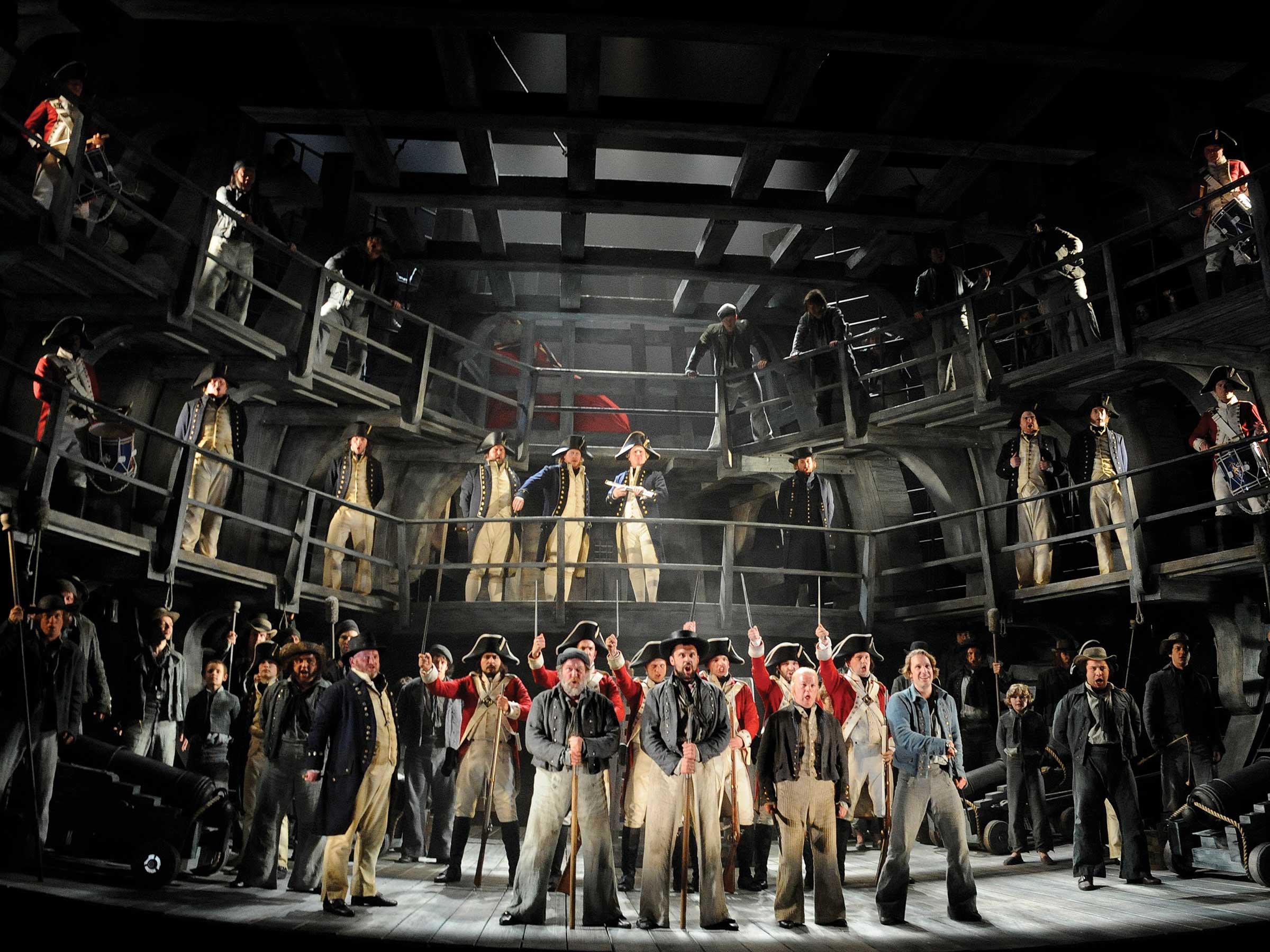

But the difficulty offered by Melville’s work must have served as a stimulus rather than a deterrent to Britten and his librettists, E.M. Forster and Eric Crozier. Turning to the opera after immersing oneself in the compelling though gloomy world of Melville’s story, one encounters a work of tremendous vitality, energy, and dramatic variety. While we mainly grasp Melville’s characters as figures in a morality play, deeply tinted by and never entirely free from the narrator’s deep melancholy, Britten’s characters instantly have their own life and the score quickly establishes the man-of-war, HMS Indomitable, as a world unto itself where an action of consequence is going to happen. While Melville’s novella is a report on this action, Britten’s opera is a vivid representation of it.

While generically the two works are as different as can be, Britten and his librettists sustain and expand Melville’s thematic interests. Britten’s characters never quite lose the air of being in a morality play. Claggart, the master-at-arms who accuses Billy of mutiny and is felled by Billy, is not presented as an object of psychological enquiry. He is clearly disturbed by Billy’s physical beauty—the homoerotic subtext is powerful throughout—but his hatred for him arises from his sense that Billy stands for all that he, Claggart, does not; therefore, Billy must be destroyed. Claggart’s music, reminiscent both of Verdi’s Grand Inquisitor and Iago, articulates the deepest malice. Billy, in contrast, is generous, naively trusting, and above all a Christ-like figure who instills joy in whoever he encounters. Between them is Captain Vere, the most complex figure in the opera, divided between his duty as the commander of the ship who is obliged to obey the Articles of War and his acute awareness of both Billy’s innocence and the strong attraction he feels toward him. It is through Vere’s helplessness that we become aware of the utterly impersonal nature of the law that compels the tragic conclusion.

However, neither Melville nor Britten are prepared to accept law as the ultimate truth. In both the novella and the opera, Billy sustains his radiance to the end, even blessing Captain Vere, as he is dragged to the yardarm. But in the opera, there is a greater presence behind and around Billy. This is apparent in the opening scene, as the sailors are scrubbing the decks; the orders of midshipmen and petty officers, accompanied by jagged phrases on the brass and winds, fly around like hostile and invasive insects that attempt to torture the men. The sailors, however, are indifferent. They repeat a dirge-like strain in which we hear the stirrings of the ocean. Sonically, the crew is identical with the dark, swirling waters around them, which suggests that they are closer to nature and to the reality of things than to the authority that contains them on the ship. Billy especially is associated with this realm of nature; as we hear him sleeping in act one, in music strikingly akin to the choral passages of the sailors, he dreams he lies at the bottom of the ocean, and later, before his execution, in a deeply moving solo, he welcomes his coming sleep where “the oozy weeds about me twist.” Salvation comes, it is implied, in acceptance of one’s natural being and surrender to it. All else, including the cruel authority of the military, is irrelevant, trivial even. Billy reaches that understanding when he imagines he sees “a far-shining sail, that’s not fate and I’m contented.” At the opera’s end, Vere thinking back on the events on the HMS Indomitable, also sees “that far-shining sail” and he too is content. What that contentment is might well be the question we should ask ourselves as we leave the opera house.

Simon Williams is emeritus professor in the Department of Theater and Dance at the University of California Santa Barbara, author of four books on German theater, and lecturer on the history of acting, Shakespearean performance, and opera as drama.